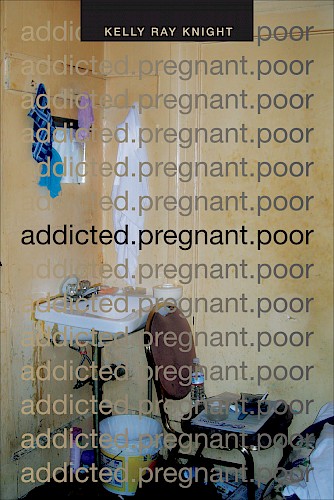

addicted.pregnant.poor

Kelly Knight

— Reviewed by

Kelly Knight, addicted.pregnant.poor. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015, $14.99 (Kindle edition)

While much been written about drug use, mental illness, homelessness, and urban poverty (Estroff 1981; Martin 2009; Page and Singer 2010; Singer 2005, 2006; Susser 2012; Waterston 1997), very few anthropological studies have taken privately owned daily-rent hotels as their ethnographic sites. Kelly Knight’s ethnographic study is therefore significant, moving ethnographic inquiry into relatively unfamiliar terrain and offering insight into the processes that enable an entire population of addicted, pregnant, and poor women who live and work in these spaces to remain hidden in plain sight.

Kelly Knight’s addicted.pregnant.poor is based on four years of ethnographic work conducted among this population, living in daily-rent hotels on and around San Francisco’s Mission Street. Knight’s broad yet detailed and carefully argued analysis draws connections between and among different registers (for example, public health, law, science, and popular culture.), inviting readers into a complicated world where disorder functions as an organizing logic for a system within which institutional boundaries, scientific categories, and social identities are continually renegotiated.

Knight’s book begins with an analysis of the relationship between the management of daily-rent hotels and their tenants, whose socioeconomic hardships are exploited by managers in their relentless pursuit of profit. In outlining the enabling relationship between these establishments and their addicted and pregnant tenants, Knight illustrates the ways in which the drug–sex economy in San Francisco is marked by instability, which shapes the lives and identities of the women studied, along with the ways they are made visible as addicts and mothers-to-be.

Chapter 2 explores the relationship between addicted pregnancy and time. As Knight argues, to be addicted, pregnant, poor, and female entails being repeatedly pulled into and out of different temporalities. Highlighting the fluidity and multiplicity of time and identity also provides an opportunity for Knight to unpack the various social scientific debates that have tended to fix women into stable categories while ignoring the fact that their everyday experiences are anything but.

In her third chapter, Knight chronicles historical transformations in public health. In particular, the rise of the ‘neurocrat’ is addressed – this being a civil servant whose role is to ‘make the madness of poverty legible’ (loc. 2540). The neurocrat is charged with aggregating medical information about a particular addict and distinguishing symptoms of mental illness from symptoms of addiction. In doing so, the neurocrat transforms health claims into economic claims in the form of monetary benefits for the drug user. As Knight shows, the increasing number of addicts bereft of social support has functioned as a catalyst for the rise of this neurocratic expertise.

In chapter 4, Knight examines another kind of expertise, which is mobilized by addicted, pregnant women as they engage in ‘street psychiatrics’ – practices that include self-diagnosing and self-medicating with stimulants, opiates, alcohol, and more. These practices, Knight shows, are not always purely recreational, but rather strategic: women who self-medicate with crack, a stimulant known for amplifying aggressive behavior, often do so not to get high but to preserve the energy and aggression that is required for survival on the street. In the fifth chapter, Knight discusses the ways in which addicted, pregnant women are represented in popular culture, often in overly simplified and demonizing terms. Specifically, she analyzes moral panics that formed around the idea of the ‘crack baby’, showing how this discourse obfuscates the complex reality of addicted pregnancy and defines addicted pregnant women as inevitably ‘toxic moms’, incapable of love and unworthy of social, medical, or financial support.

Faced with these obstacles, what kinds of interventions are available for these women? Knight addresses this question in her sixth chapter, where she details the ways in which addicted, pregnant women advocate for themselves and their children in their pursuit of social support, by ‘hustling the system’ that hustles them (loc. 3863). The relationship between these women and the public health system, Knight demonstrates, is deeply ambivalent. The same system that provides much-needed services also acts as a ‘revolving door’ that periodically pulls them back inside, ‘only to fling them back out shortly afterward, then back in again, then back out’ (loc. 3679). In response to these challenges, Knight advocates for a ‘vital politics of viability’, which requires adopting a complex view of pregnancy and addiction as social problems that demand acknowledgement. While the specific dimensions of such a politics warrant further elaboration, Knight provides an empathetic starting point for reconsidering the ways in which we understand addicted pregnancy in the United States today.

Perhaps what is most impressive about Knight’s book is the amount of time and effort she spends negotiating her own subject position as an anthropologist/advocate/mother/friend. Knight is relentlessly self-reflexive, constantly discerning her multiple positions and the personal, political, and ethical stakes involved in her occupying these different roles. She is critical, both of herself and of sometimes ‘vulturistic’ anthropological pursuits. Ethnographers, she insists, must contend with the predatory tendencies of human subjects-based research.

Indeed, Knight practices as she preaches. Her book offers a richly polyvocal account of addicted pregnancy, in which the voices of her subjects are inserted directly into its pages. Moreover, Knight takes an important step toward debunking the long-held assumption that addicts are inherently irrational subjects, unable to think or act on their own behalf. On the contrary, the real-time conversations Knight incorporates into her book demonstrate the myriad ways in which addicted, pregnant women exercise their knowledge and skills, not only to survive, but to understand and manage the irrationality of their everyday lives and the bureaucratic systems that attempt to regulate them. Knight’s book provides a strikingly honest and well-argued perspective on addicted pregnancy, one that presents these women in all their complex humanity, and should serve as a high standard for other authors, whether they are anthropologists, social scientists, medical researchers, or public health officials attempting to reconsider how we think about the politics of addiction today.

About the author

Melina Sherman is a PhD candidate in the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Southern California.