Through our eyes

—

This photo essay draws on photographs and narratives created as part of an ongoing community-based photo-voice project. The aim of this project is to visually explore the gendered dimensions of HIV stigma, disclosure, and criminalization among diverse groups of women and transgender people living with HIV in Vancouver, Canada.

Despite significant advances in HIV treatment and prevention technologies, HIV-related stigma continues to significantly hamper access to care and the quality of life of people living with HIV. The criminalization of HIV non-disclosure is one example of how HIV-related stigma manifests itself at a structural level. Despite strong recommendations by the World Health Organization and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS against the use of criminal laws to govern HIV prevention, more laws continue to be passed and more people than ever are prosecuted under these laws worldwide. Canada stands out in its assertive approach to criminalizing HIV nondisclosure and has produced the second highest number of convictions, after the United States. In Canada, HIV nondisclosure is most commonly prosecuted as sexual assault. This constitutes one of the most severe charges in the Canadian Criminal Code and includes mandatory registration as a sexual offender. While the criminalization of HIV nondisclosure is often portrayed as an effort to protect women, emerging research suggests that criminalizing HIV nondisclosure may in fact have particularly negative effects on women living with HIV by fostering fear of prosecution, abuse, and violence (see Siegel, Lekas, and Schrimshaw 2005). These negative effects are exacerbated for marginalized women living with HIV, especially women living in poverty, sex workers, and immigrant and refugee women (who face mandatory HIV testing as part of the immigration process).

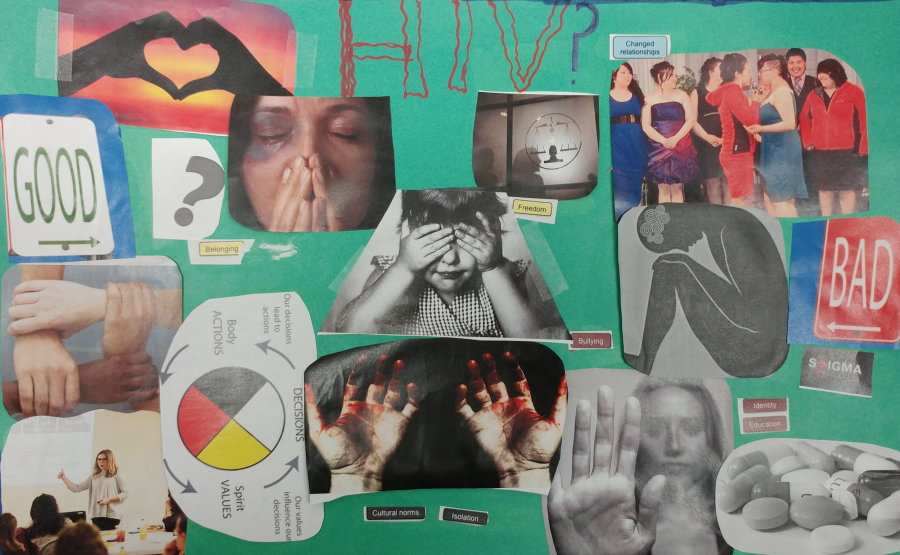

In this photo essay, we present photographs taken by a group of five African immigrant and refugee women living in Canada, and excerpts from their narratives on the topics of HIV stigma, disclosure, and criminalization. These women were invited to participate in this community-based, participatory photo-voice project via their membership in an existing support network for African immigrants run by our community partner, the Afro-Canadian Positive Network of British Columbia. The participants came together for a series of six meetings over the course of two months in the fall of 2016. The group was facilitated by a qualitative researcher and a peer researcher, and the curriculum that guided the six meetings was developed collaboratively with the study’s peer research team. It included education on the criminalization of HIV nondisclosure in Canada and a workshop on photography and the visual expression of ideas and experiences. In this workshop, participants created collages on the topics of HIV disclosure, stigma, and the law (see image 1 for an example). Our goal was to create a safe space for women to share their experiences, both visually and verbally. The participants worked collaboratively to decide which images and narratives they wanted to foreground and discuss.

Giving voice to images

Speaking about her collage, Tee[note 1] started off by asking the group, ‘What is behind HIV that we cannot talk about?’ Pointing to the picture on the top right corner, Tee reflected:

Knowing my status completely changed my relationships. I feel like I don’t belong and that is stigma. The hand [with the palm facing straight out] means ‘I just want to be alone’. … And say you decide to be in a relationship, once your partner finds out you are HIV positive they bully you and physically abuse you. For us African [immigrant and refugee] women, we are not so sure of what our rights are. We don’t report abuse most times because we are scared. What if we are arrested? Say we have kids, how are they going to survive? So you keep that to yourself. The hands with blood [represent that] you are beaten and bullied. You keep [stay in] that relationship because you are afraid that the person will report you. … So women live in fear.

Social isolation and loneliness were prominent themes in the women’s photographs and discussions, and two of the most negative influences on their daily lives. In narrating her collage, Tee described an explicit link between social isolation and the vulnerabilities of women living with HIV to violence and blackmail by intimate partners. In a context where HIV is criminalized, the threat of charges looms large – even when a woman has disclosed her HIV status to her partner – and can be a powerful force in keeping women in abusive relationships.

A notable detail in Tee’s collage is the fact that the picture of HIV medications is placed on the ‘bad side’. Her decision to place the medications there would seem to echo academic debates regarding the false promise of ending HIV-related stigma with treatment alone (see Doyal and Doyal 2013). For most of the women in the group, storing HIV medications in their homes or handbags carried a risk of inadvertently revealing their HIV status to intimate partners, roommates, visitors, or family members. While silence and conscious acts of nondisclosure could be important concealment tactics for these women as they navigated their home lives and broader social worlds (see Moyer 2012), inadvertent disclosure could result in severe consequences, such as the loss of housing and employment.

Babsy’s photograph further expressed the theme of social isolation, as well as a need or desire to ‘hide’. She explained: ‘I cover my face, I’m ashamed because of the sickness. … I don’t know where it came from, only God knows, so I’m ashamed. … You are the enemy. Nobody wants to come near you’.

Shingi similarly reflected on a self-portrait of herself in a mask: ‘I feel like I’m a scary, scary, scary thing. Maybe that’s because of the HIV. … I just feel like I’m a monster’.

For many women in the group, the stigma they felt from their own diasporic communities amplified feelings of shame and fears surrounding HIV disclosure. Participants spoke about how, within the local African immigrant community, living openly with HIV was discouraged by some, often because of worries that this openness would reinforce broader, racialized discourses that associate Black bodies with HIV (Fassin 2007). These community-level worries contributed to some women’s reluctance to access HIV-specific services. Women feared that even being in the vicinity of these services could inadvertently reveal their HIV status and lead to severe discrimination and consequences. Sherry explained her photograph of a painting of a stormy sea: ‘The storm has come. … It is a storm of anger, discrimination, and racism. We are being discriminated [against]. I didn’t do any crime. We need to look to Jesus … and pray that one day he may come and rescue us. When he comes to rescue us, we are going to be weighed on the scale. All of us. There’s no small sin, no big sin’.

Sherry depicted her experience of the intersection of racism, stigma, and criminalization as a storm and, like many other participants in the group, referenced religion as one of the most important means of coming to terms with experiences of living with HIV. Participants’ religious beliefs also shaped the participatory, peer-based process of the project itself in interesting ways. For example, while participants were in unanimous agreement about the use of prayer to open and close each meeting, difficult discussions arose during meetings about the effectiveness of prayer in the treatment of HIV. A local pastor was promoting the idea that HIV could be cured by prayer alone, and this notion was particularly attractive to some women, given their fears of being involuntarily ‘outed’ as living with HIV as a result of accessing biomedical forms of treatment and HIV-specific community-based services. Women’s debates about the value of prayer as a treatment for HIV brought to light tensions among participants around what it meant to conduct oneself as a ‘responsible’ and ‘deserving’ HIV-positive immigrant subject in their relatively new home (Canada), which a number of women strongly equated with accessing HIV medications and HIV support services (Biehl 2007).

In addition to stigma and fears surrounding HIV disclosure, the women who participated in this project faced complex trauma rooted in past experiences of political and sexual violence, limited access to local support services, and language barriers. Creating and maintaining a safer space for participants to explore the impacts of criminalization on their daily lives was therefore a constant challenge. Despite some tensions, such as those described above, participants consistently stressed the significance of being able to share their stories, witness each other’s pain, and provide mutual support. Any challenges that emerged during the project were significantly ameliorated by the participation of the peer facilitator and a prominent community leader (who was one of the five participants). Their presence in the group, and their willingness to share their own experiences of living with HIV, aided tremendously in opening up, bridging, and focusing conversations, and in encouraging other participants to share their own stories. The peer facilitator and community leader also checked in with participants between meetings, to answer questions and debrief concerns that emerged from the group work or while taking photographs.

While trauma and violence were prominent themes, participants also used this project to represent and discuss their resilience in the context of stigma, racism, poverty, and criminalization. In a photograph titled ‘Appreciation’, Tee captured a plant she had planted when she first arrived in Canada. Tee explained, ‘I planted this flower when I came to Canada. I’ve been watering this plant every day. … It shows my strength, and how much I’ve grown from the time I was diagnosed with HIV. … As this tree grows, it gives me hope at all time. I’m living a healthy life, and thank God every day about life’.

The images and narratives that emerged from this project directly contradict the notion that the criminalization of HIV nondisclosure ‘protects’ these and other women.These visual and narrative explorations of women’s experiences of HIV stigma, disclosure, and criminalization highlight linkages between social isolation, shame, abuse, and racialized discourses about HIV and Black bodies, and underscore how these linkages exacerbate the suffering of some African immigrant and refugee women living with HIV in Vancouver. Images of masks and backs turned towards the camera reflect an imperative to hide one’s HIV status, not only from intimate partners but also from the African immigrant community. These depictions of ‘hiding’ were juxtaposed with the legal imperative to reveal one’s status to intimate partners, and a sense of moral responsibility to access HIV medications and join support networks like the Afro-Canadian Positive Network of British Columbia, albeit at the risk of disclosure. African immigrant and refugee women living with HIV in Vancouver navigate these dual imperatives – to hide and to reveal – in the context of numerous daily challenges, as well as their own significant resilience and strong religious beliefs.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our peer research team for their insights and support in conceptualizing and carrying out the project: Flo Ranville, Patience Chamboko, and Lulu Gurney. We are also indebted to the women who participated in this project and so generously shared their perspectives and stories with us. Thank you to Sarah Moreheart and Heidi Safford for their logistical support with organizing the groups. This work is supported through trainee awards from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research, and through Vancouver Foundation (UNR16-0467) and CIHR Community-Based Research grants (CBR-151184).

About the authors

Andrea Krüsi is a research scientist with at the Gender and Sexual Health Initiative (GSHI) of the British Columbia Centre of Excellence in HIV/AIDS in Vancouver. Karina Czyzewski is a qualitative researcher at GSHI and a social worker at the Pender Community Health Clinic in Vancouver. Patience Magagula is the Executive Director of the Afro-Canadian Positive Network of British Columbia.

References

Biehl, Joao. 2007. Will to Live: AIDS Therapies and the Politics of Survival. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Doyal, Lesley, and Doyal, Len. 2013. Living with HIV and Dying with AIDS: Diversity, Inequality, and Human Rights in the Global Pandemic. Farmham: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

Fassin, Didier. 2007. When Bodies Remember: Experiences and Politics of AIDS in South Africa. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Moyer, Eileen. 2012. ‘Faidha Gani? What's the Point: HIV and the Logics of (Non)-Disclosure among Young Activists in Zanzibar’. Culture, Health & Sexuality 14(sup1): S67–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2012.662524.

Siegel, Karolynn, Helen-Maria Lekas, and Eric W. Schrimshaw. 2005. ‘Serostatus Disclosure to Sexual Partners by HIV-infected Women before and after the Advent of HAART’. Women & Health 41, no. 4: 63–85. https://doi.org/10.1300/J013v41n04_04.

Endnotes

1 Back

All names are pseudonyms chosen by the participants.