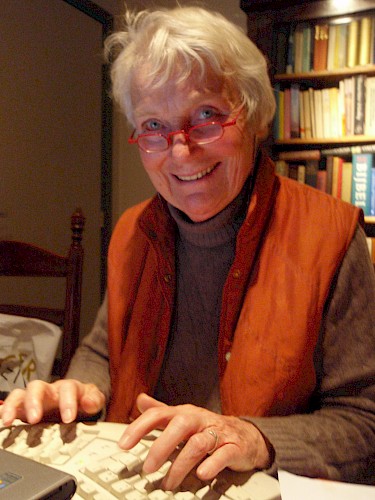

Remembering Corlien M. Varkevisser (1937–2017)

—

Corlien Varkevisser, Emeritus Professor of Interdisciplinary Research for Health and Development at the University of Amsterdam, died on 8 December 2017. Born in 1937 in Katwijk aan Zee, a small picturesque fishing town in the Netherlands, Varkevisser was the second of three daughters in the family of the head of the local fishing school. After high school and teacher-training college, followed by one year as a primary school teacher, she started studying social geography at the University of Amsterdam. André Köbben,[note 1] then Professor of Cultural Anthropology, sparked her interest in anthropology, and she eventually graduated with a degree in social geography and cultural anthropology. After graduation she was invited to join a multidisciplinary research team that was to study socialization and school education in Tanzania. As a female anthropologist with experience in teaching primary school, she was considered an ideal candidate to study the socialization of young children within the family context. The research team included two sociologists, a human geographer, a psychologist, and a pedagogue, and was led by the anthropology professor Jan van Baal.[note 2]

The fieldwork lasted from 1964 to 1967. Initially, Varkevisser did not want to write a doctoral dissertation based on her research, feeling that she could not ‘throw’ 3,500 pages of raw data into one dissertation, despite pressure from Van Baal. The fact that he was also her employer at the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT) further complicated the situation. Later on, she said about this period that both her fieldwork and her ‘fight‘ with van Baal had taught her lessons that would serve her for the rest of her life. The solution came when she found another PhD advisor, returning to study under the supervision of Köbben, and in 1973 she obtained her doctorate. The thesis was published under the title ‘Socialization in a Changing Society: Sukuma Childhood in Rural and Urban Mwanza’.

Following her graduation in 1964, Varkevisser worked for her entire career until her retirement in 2000 at the Royal Tropical Institute in Amsterdam, from which she conducted research on the cutting edge of anthropology and public health in twenty-three countries: Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Egypt, Indonesia, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Mali, Mauritius, Mozambique, Niger, Papua New Guinea, Seychelles, Somalia, South Africa, Sudan, Swaziland, Tanzania, Yemen, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. The topics of her applied medical anthropology projects included: leprosy and TB (Kenya and Tanzania), TB compliance (Botswana), stigmatization in leprosy (Papua New Guinea, Indonesia, Nigeria, Nepal, and Brazil), female circumcision (Sudan), and training in health systems research, rapid rural appraisal, and nutrition.

In 1980 Varkevisser founded the Primary Health Care (PHC) group together with Pieter Streefland[note 3] within the Rural Development Department of KIT. She benefitted from the political tide. Following the Alma Ata conference, the Dutch government had embraced the notion of PHC and the PHC group expanded, especially following a PHC conference in Burkina Faso, partly organized by Varkevisser. In 1981 she completed a master’s degree in public health, alongside the many other commitments she had at KIT. Between 1982 and 1987 Varkevisser visited many PHC projects supported by the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs in West Africa (Benin, Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso) and in Angola, Mozambique, Tanzania, Sudan, and Yemen.

In 1987 Varkevisser went to Zimbabwe to lead the Joint Health Systems Research Project, hosted by the World Health Organization’s subregional office in Harare. There she worked in an interdisciplinary team with many colleagues in some fourteen countries in southern Africa on one of her most important and widely used publications, Designing and Conducting Health Systems Research Projects, which is a two-part research guide, consisting of training modules to be used in education and training. Together with Indra Pathmanathan and Ann Brownlee she wrote the manual in 1991 and revised it in 2003/04 (Varkevisser et al. 2003/2004). During her time as coordinator of the project, trainees carried out about fifty small research projects as part of their training. In addition to providing training in research, this project also succeeded in getting health systems research onto the agenda of various ministries of health in southern Africa.

In 1992 she returned to the Royal Tropical Institute in Amsterdam, where she became coordinator of the International Course in Health Development, a master’s-degree program in Public Health, from 1994 through 1997. Varkevisser supervised many students in writing their master’s theses.

Two years later, in 1994, an intensive and fruitful collaboration began with the University of Amsterdam. Varkevisser became Professor by Special Appointment on behalf of the Royal Tropical Institute, with the assignment of ‘Interdisciplinary Research for Health and Development’. In her inaugural speech, she argued for a more participatory, applied, and interdisciplinary medical anthropology. At that time she was very active in teaching and supervising students in a course entitled ‘Health and Health Care in Developing Countries’ at the Institute of Development Research Amsterdam (InDRA) and in the international Amsterdam Master’s of Medical Anthropology (AMMA) program. In that period she also supervised five PhD students in the field of medical anthropology and health systems research. As a professor ‘by special appointment’ she was supposed to spend one day per week at the university, but she did so much teaching and supervising that she had to extend her working hours considerably and even met students at her house on the weekends. When I read her report on her activities as professor in the 1995–1996 academic year, I was overwhelmed by her energy and unstinting enthusiasm.

Varkevisser’s research guide on conducting health systems research was the basis for the manual that Anita Hardon and a large number of coauthors (2001) later wrote for a series of five-week courses in Thailand, Bangladesh, and the Philippines, and for the methods module used in the AMMA and the Master’s of Medical Anthropology and Sociology programs at the University of Amsterdam. The manual was and continues to be used in many programs in countries of the ‘South’, such as in the Public Health Master’s program at BRAC University, Bangladesh. Varkevisser was one of the first to link qualitative medical anthropological research to quantitative approaches and interventions, and to convert these into excellent training programs. She inspired many people and that inspiration has likely worked its way through to many others who may not even know that Varkevisser was behind it. Partly because of her efforts, medical anthropology became attractive and useful for doctors and paramedics.

Also worth mentioning is the important role she played in the world of leprosy, where she sought and received attention for gender issues and the role of stigma. See for example her case studies in Indonesia, Nigeria, Nepal, and Brazil, at: https://www.lepra.org.uk/platforms/lepra. In 1999 she received the Eijkman Medal for her contributions to the field of tropical medicine.

Let us look more closely at Varkevisser’s anthropological approach to health systems research. Her primary intention was to stimulate communication among the various actors involved in the provision of health care and to use this as a stepping stone to improve the quality of health care. She was convinced that suggestions for improvement should not be imposed from outside but should originate from self-analyses by those involved in caregiving and the planning of services. In her view, those working in the health system know the system best, are best placed to improve existing routines, and also often benefit themselves from improvements. She argued that health personnel should be trained in conducting research and formulating research questions about their own clinics and services. Staff members would be willing and motivated to answer these questions, and moreover the questions would be considered more relevant than questions asked by outsiders. An important additional objective of such health systems research was building the capacity of local health researchers and research trainers.

Varkevisser did not stand above health workers as a researcher, but with them. She offered various skills and insights for listening to people and looking for the underlying causes of malfunctioning services. She was deeply interested in people and passed on this enthusiasm for the human dimension in her approach to health systems research.

A crucial factor determining the quality of health care, Varkevisser repeatedly stressed, is the quality of information on which policy makers base their decisions. Very often this information is vague or missing altogether, and decisions regarding interventions can therefore be completely off track, leading to a waste of money. In the research guide, she and her coauthors (2003/2004, 14) list some basic questions that health policy makers need to take into account:

- What are the health needs of (different groups of) people, not only according to health professionals but also according to the people themselves? Can shared priorities be agreed upon?

- To what extent do the present health interventions cover these priority needs? Are the interventions acceptable to the people in terms of culture and cost, especially to the poor? Are they provided as cost effectively as possible?

- Given the resources we have, could we cover more needs, or more people, in a more cost-effective way? Is it possible to introduce or expand cost-sharing through insurance, to reduce the risk of unexpected high costs, in particular for the economically vulnerable? Could cooperation with the private/NGO sector be improved? Could donor agencies help to solve well-defined bottlenecks in the system?

- Is it possible to better control the environmental factors that influence health and health care? Can other sectors help (education, agriculture, public works/roads, etc.)?

A 1994 monograph brought together some eighty health systems research studies carried out between 1988 and 1993 in thirteen countries in southern Africa (Joint Project on Health Systems Research for the Southern African Region [Joint Project] 1994). Topics involved maternal and child health, family planning and nutrition, disease control, primary health care, HIV/AIDS, and management issues. The recommendations offered by several of these studies, addressing the questions mentioned above, have been implemented.

When describing a health system, the authors mention community members and public authorities as the two opposing poles of the system (Joint Project 1994, 9; emphasis added):

everywhere individuals form part of a network of family and community members who are concerned about their health. This network prescribes or advises how to prevent illness and what to do in case of ill health. In many societies, mothers and grandmothers are key figures in early childcare. They determine nutritional and hygiene practices, alert children to dangers, provide care in case of disease, and teach children the basics of self-care. … A public authority is responsible for the well-being of all people inhabiting its territory. Nowadays governments of states organise public health care and, to some extent, regulate private health care initiatives.

But one of the limitations of the health systems research model is that community members and public authorities are little involved in the research. Public health at the end of the 1980s and in the 1990s was deeply affected by worldwide structural adjustment programs, when governments had to ‘reform’ their systems to meet the demands of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. The voice of the authorities struggling with imposed restrictions and austerity measures was, however, little heard in the discussions about health systems research.

Similarly, community members who were the ultimate users of health care were rarely directly involved in the development of research protocols. Varkevisser was aware of this, but admitted that for practical reasons this was often unavoidable. She tried to remedy their absence by involving them before and after the workshops, explaining: ‘Advice to consult community key informants on selected problems before a workshop and testing interviews in communities around the workshop location to some extent ensured community involvement, as well as obligatory testing of the research design in the home area before starting full implementation’ (Varkevisser et al. 2001, 288–89).

In spite of these limitations, health systems research proved to be a powerful tool in its concept of using anthropology and involving practitioners and health program implementers in operational research. This was Varkevisser’s major contribution, and one that she applied throughout her career to public health in general as well as to specific health problems such as leprosy, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS. Key to the success of health systems research was that the researched became researchers who experienced trust and respect from a foreign anthropologist entering their world. There is a common saying in Dutch that a butcher should not be allowed to test his own meat. The underlying principle is mistrust, the assumption that individuals are inclined to cheat for their own benefit. The assumption in Varkevisser’s approach was the opposite: people are basically inclined to do a good job and want to enjoy the benefit of their good performance. Respect, engagement, and charm were the secret weapons of her anthropological ‘methodology’.

A few years after her retirement she wrote in a reflection on her professional life:

Looking back on my life as an anthropologist I realize that applied medical anthropology is not an impossible thing to do, nor a diluted or immature kind of anthropology. Risking to sound self-complacent I can only conclude from the many projects I have been involved in over the years that anthropology matters. Anthropology, and medical anthropology in particular, can make a difference. It is a conclusion that fills me with undiluted gratitude in my retirement. (Varkevisser 2010, 143)

Varkevisser died at the age of eighty and left behind a large international circle of friends and colleagues. The fact that many children in diverse countries bear her name is a significant sign of the widespread appreciation for her work and personality.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Leon Bijlmakers, Jarl Chabot, Amanda Le Grand, Marian Paape, Anny Peters, and Ria Reis for their help in getting the facts right and commenting on earlier versions of this text.

References

Bovenkerk, Frank, Frank Buijs, and Henk Tromp, eds. 1990. Wetenschap en partijdigheid: Opstellen voor André J.F. Köbben. Assen/Maastricht: Van Gorcum.

De Ruijter, Arie, and Jan de Wolf, eds. 1993. Jan van Baal 1909–1992. Special issue Antropologische Verkenningen 12 (3) 1–80.

Hardon, A., P. Boomongkon, P. Streefland, M.L. Tim, T. Hongvivatana, J.D.M. van der Geest, A. van Staa, and C. Varkevisser, eds. (1994) 2001. Applied Health Research Manual: Anthropology of Health and Health Care. Amsterdam: Het Spinhuis.

Joint Project on Health Systems Research for the Southern African Region. 1994. Summaries of Health Systems Research Reports 1988–1993. Harare: Joint Project on Health Systems Research for the Southern African Region.

Strating, Alex, and Jojada Verrips. 2005. ‘A Stickler for Words: An Interview with André J.F. Köbben’. Etnofoor 18 (2): 9–21.

Van der Geest, Sjaak. 2008. ‘Obituary Pieter Hendrik Streefland (1946–2008)’. Medische Antropologie 20 (1): 164–65.

Varkevisser, Corlien M. 2010. ‘Why Medical Anthropology Matters: Looking Back on a Career’. In Doing and Living Medical Anthropology: Personal Reflections, edited by Rebekah Park and Sjaak van der Geest, 131–44. Diemen: AMB Publishers.

Varkevisser, Corlien M., Gabriel M.P. Mwaluko, and Amanda le Grand. 2001. ‘Research in Action: The Training Approach of the Joint Health Systems Research Project for the Southern African Region’. Health Policy & Planning 16 (3): 281–91.

Varkevisser, Corlien M., Indra Pathmanathan, and Ann Brownlee. (1991) 2003/2004. Designing and Conducting Health Systems Research Projects. 2 vols. Amsterdam: KIT Publishers, IDRC Ottawa and Regional Office for Africa. http://archives.who.int/prduc2004/Resource_Mats/Designing_1.pdf

Publications by Corlien Varkevisser

A large part of Varkenvisser’s written work consists of so-called grey literature: reports and recommendations based on her innumerable research projects, advisory work, and consultancies. The fortunate paradox of grey literature is that it may never come to the attention of the academic community but does reach the people who are most involved in the research and most affected by its conclusions and recommendations. This fairly complete overview of her written work, listed in chronological order, is intended to inform academic colleagues about the often-hidden contributions of applied medical anthropology.

Varkevisser, C.M., and E. van der Zee. 1963. Het Tropenmuseum en zijn publiek; een onderzoek naar de samenstelling van het publiek en naar zijn mening, houding en gedrag ten aanzien van het museum, in opdracht van het Koninklijk Instituut voor de Tropen, uitgevoerd onder ausp. van de Sociografische Werkgemeenschap van de Universiteit van Amsterdam. Amsterdam: KIT.

Varkevisser, C.M. 1966. The village organisations of Sukumaland; observed in Bukumbi. Nyegezi Social Research Institute. The Hague: CESO.

Varkevisser, C.M. 1969. Growing up in Sukumaland. Groningen: Wolters-Noordhoff. Reprinted in: Primary education in Sukumaland, 42–82.

Varkevisser, C.M., and K. de Jonge. 1972. ‘Fertility in two rural areas of Tanzania: A dependent variable’. Seminar paper given in Leiden, Afrika Studiecentrum, 18–22 December.

Varkevisser, C.M. 1972/1973. ‘The Sukuma of northern Tanzania’. In Cultural source materials for population planning in East Africa(vol. II: 224–30; vol. III: 234–49), edited by A. Molnos. Nairobi: East African Publ. House.

Varkevisser, C.M. 1973. ‘Socialization in a changing society: Sukuma childhood in rural and urban Mwanza, Tanzania’. PhD diss, CESO, The Hague.

Varkevisser, C.M. 1973. ‘Some functions and characteristics of the Sukuma Luganda clan’. Tropical Man4: 92–108.

Varkevisser, C.M. 1973. ‘Sukuma political history, reconstructed from traditions of prominent Nganda clans’. Tropical Man4: 67–92.

Varkevisser, C.M. 1974. ‘Relatie tussen opvoeding thuis en schoolopleiding: Een case-study in Mwanza district, Tanzania’. Sociaal WetenschappelijkeOefeningen 17 (5): 19–28.

Varkevisser, C.M. 1975. ‘Comparative research in leprosy control. Results of a computer analysis of patient registration cards in Mwanza region in Western Province, Kenya’. Amsterdam: KIT.

Varkevisser, C.M. 1976. ‘Vrouw en plattelandsontwikkeling in de Tropen’. Landbouwkundig Tijdschrift 88 (12): 384–89.

Varkevisser, C.M., C.I. Risseeuw, and I. Bijleveld. 1977. Integration of combined leprosy and tuberculosis services within the general health care delivery system, Western Province, Kenya. Amsterdam: KIT.

Varkevisser, C.M. 1977. TB control in Botswana: problem identification. Report of an orientation visit, June 15th–July 15th,1977. Amsterdam: KIT.

Varkevisser, C.M., and M. Paape. 1978. E’valuation of the attendance behaviour of TB patients who were registered at Athlone hospital, Lobatse, and at SDA hospital, Kenya, during 1976 and 1977, and patients' intake of medicines’. Report to the Ministry of Health, Botswana.

Varkevisser, C.M. 1978. TB health education guide for health workers and teachers. Amsterdam: KIT.

Varkevisser, C.M. 1979. ‘Community knowledge of leprosy in Papua New Guinea and its implications for case-finding and case-holding’. Report for WHO Manila. Amsterdam: KIT.

Varkevisser, C.M. 1979. ‘Discussion paper on staff and function of the TB office in Lobatse’. Report for the Ministry of Health, Botswana.

Varkevisser, C.M. 1979. ‘Methodology of research into social aspects of leprosy control’. In Proceedings of the XI International Leprosy Congress, Mexico, edited by L. Lapati et al., 173–78. Amsterdam: Excerpta Medica. Also published in: Leprosy Review50 (1979): 223–29.

Varkevisser, C.M. 1979. ‘Recent attempts in Kenya and Tanzania at integrating combined leprosy and tuberculosis in general health care: Achievements and problems’. Bulletin of the IUAT54: 368–69.

Varkevisser, C.M. 1980. ‘Principles of sociological evaluation of leprosy control programmes’. Paper presented at the Scientific Conference on the Epidemiology of Leprosy, Arusha, 109–18. Dar es Salaam: Tanzania Leprosy Association.

Varkevisser, C.M. 1980. ‘Psycho-social factors relevant to leprosy control’. Paper presented at the Scientific Conference on the Epidemiology of Leprosy, Arusha, 119–23. Dar es Salaam: Tanzania Leprosy Association.

Varkevisser, C.M. 1982. ‘Where there is no sociologist. Manual for social scientific research in leprosy control and the implementation of its results’. 17th International Course in Health Development, Amsterdam, September 1980–June 1981. (Master’s thesis.) Amsterdam: KIT.

Varkevisser, C.M., and P.H. Streefland. 1981. ‘Antropologie en Primary Health care’. IMWOO Bulletin9 (3): 22–25. Also published in Medical Anthropology Newsletter13 (2): 13–14.

Varkevisser, C.M. 1981. Evaluatie rapport Botswana TB Project voor DGIS. Amsterdam: KIT.

Varkevisser, C.M., M. Paape, and R.W.G. Stellinga. 1981. An evaluation of the Lobatse TB project 1978–1981. Technical report, Lobatse Regional Medical Office. Amsterdam: KIT.

Varkevisser, C.M. 1981. Verslag bezoek Sudan. Project ‘Epidemiology of female circumcision’. Amsterdam: KIT.

Varkevisser, C.M. 1982. Verslag van een evaluatie missie naar het project ‘Equipe medicale néerlandaise, République du Niger’, 25 January–10 February. Amsterdam: KIT.

Varkevisser, C.M. 1982. Inventarisatie van ‘Soins de Santé Primaires’ (SSP) projekten in de Volksrepubliek Benin. Amsterdam: KIT.

Varkevisser, C.M. 1982. Report on Missions to Dhamar Governorate Health Services Program. No publisher.

Bijleveld, I., and C.M. Varkevisser 1982. Leprosy control in East Africa. In The use and abuse of medicine, edited by M.W. de Vries, R.L. Berg, and M. Lipkin, 224–34. New York: Praeger.

Varkevisser, C.M. 1983. Verslag van een literatuur- en veldonderzoek naar de door SNV gesteunde Soins de Santé Primaires (SSP) projekten in Mali. Amsterdam: KIT.

Varkevisser, C.M., J. Eshuis, and A. Sjoerdsma. 1983. Soins de Santé Primaires dans huit pays Ouest-Africains Document Préparatoire pour le Seminaire sur les SSP à Bobo-Dioulasso, 19–24 September. Amsterdam: KIT.

Varkevisser, C.M., and H.T.J. Chabot. 1983. Evaluatie te velde van het projekt ‘Formation des Agents Villageois de Santé’, Benin.Amsterdam: KIT.

Varkevisser, C.M. with H. Anten. 1984. Evaluation of the PHC project in Hanang District, Tanzania, 14 July–2 August 1984.

Varkevisser, C.M. 1985. Verslag van een evaluatie van het basis gezondheidszorg projekt in de Provincie Sissili, Burkina Faso, 21 oktober–22 december 1984. The Hague: SNV.

Varkevisser, C.M. 1985. Rapport d'Évalution du projet de developpement des Soins de Santé Primaires dans la Province de la Sissili au Burkina Faso. Ouagadougou: Min. de la Santé Publique.

Streefland, P.H., and C.M. Varkevisser. 1985. Variations in primary health care. International symposium on Effectiveness of Rural Development Co-operation. Amsterdam: KIT.

Van Praag, E., and C.M. Varkevisser. 1985. ‘Primary health care: Achtergrond, problemen en perspectieven’. Medicus Tropicus23 (5): 1–2.

Van Praag, E. and Varkevisser, C.M. 1986. ‘Primary health care: Achtergrond, problemen, perspectieven’. Medisch Contact41 (2): 41–43.

Varkevisser, C.M. et al. 1986. Utilisation de la méthode de Sondage Rapide pour evaluer l'ampleus et les causes de la malnutrition. Bénin: Projet de Développement de Pahou.

Varkevisser, C.M. et al. 1986. The Church MCH Program in Tanzania. A study in relation to the Mother and Child Health (MCH) and Primary Health Care (PHC) programmes. Amsterdam: KIT.

Varkevisser, C.M. 1987–1989. Reports of country visits to Angola, Lesotho, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Seychelles, Mauritius, Mozambique, Tanzania. Identifying capacity, achievements and needs with respect to Health Systems Research. Amsterdam: KIT.

Varkevisser, C.M. 1989. ‘Health systems research in Africa: Scope, achievements, needs and constraints’. Keynote address for the African Regional Conference of the International Epidemiological Association, Harare, 7–12 August.

Varkevisser, C.M., E.M. Alihonou, S. Inoussa, and L. Res. 1990. Interface des soins de santé de base et des soins de santé communautaires, Benin. In Les Soins de Santé Primaires, edited by J. Chabot and P. Streefland, 97–109.Amsterdam: Royal Tropical Institute.

Varkevisser, C.M., Y. Nuyens, and G. Stott. 1990. Health systems research: Does it make a difference?Geneva: WHO.

Varkevisser, C.M., I. Pathmanathan, and A. Bronlee. 1991. Designing and conducting health systems research projects. Ottawa: WHO/IDRC.

Alihonou, E., S. Inoussa, L. Res, M. Sagbohan, and C.M. Varkevisser. 1993. Community participation in primary health care. The case of Gakpé, Benin. PDS-Pahou series vol. 1b. Amsterdam: KIT Press.

Varkevisser, C.M., E. Alihonou, and S. Inoussa. 1993. Rapid appraisal of health and nutrition in a PHC project in Pahou, Benin. Methods and results. PDS-Pahou series vol. 2b. Amsterdam: KIT Press.

Varkevisser C.M. 1995. ‘Women's health in a changing world: A continuous challenge’. Tropical & Geographical Medicine(47): 186–92.

Varkevisser C.M. 1995. ‘Culture and health: Possibilities and limitations with respect to the provision of culture-sensitive health care’. In Cultural dynamics in development processes, edited by A. de Ruijter and L. van Vucht-Tijssen, 202–22. The Hague: Unesco.

Varkevisser C.M. 1995. ‘Cultuur en gezondheid: De 'modern common wind' als ziektebrenger’. In Cultuur, identiteit en ontwikkeling, edited by G.D. Thijs, 112–29.Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit.

Varkevisser C.M. 1996. Health systems research: De knikkers en het spel.Amsterdam: Koninklijk Instituut voor de Tropen (oratie).

Dubbeldam R.P., H.T.J. Chabot, and C.M. Varkevisser 1996. ‘Better health in Africa: De nieuwe leidraad voor gezondheidszorg in Afrika?’ Medicus Tropicus 34 (4): 1–5.

Varkevisser C.M. 1996. ‘Factors contributing to under-utilization of TB services in Southern Africa’.Health systems research: It can make a difference, vol. 3. Harare: Joint Health Systems Research Program.

Varkevisser C.M. 1998. ‘Social sciences and AIDS: New fields, new approaches’. In Problems and potential in International Health, edited by Pieter Streefland, 29–51. Amsterdam: Spinhuis.

El-Karimy, E., M. Gras, C. Varkevisser, and A. van den Hoek .2001. ‘Risk perception and sexual relations among African migrants in Amsterdam’. Medische Antropologie13 (2): 301–22.

Varkevisser, C.M., G.M.P, Mwaluko, and A. le Grand. 2001. ‘Research in action: The training approach of the joint health systems research project for the Southern African region’. Health Policy & Planning 16 (3): 281–91.

Varkevisser, C.M. 2001. ‘Commentaar: Over tweelingen en chiefs in Sukumaland’. Medische Antropologie13 (2): 265–67.

Idawani, C., M. Yulizar, P. Lever, and C. Varkevisser. 2002. Gender, leprosy and leprosy control: A case study in Aceh, Indonesia. Amsterdam: KIT Press.

Moreira, T.M.A., and C.M. Varkevisser,. 2002. Gender, leprosy and leprosy control: A case study in Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil. Amsterdam: KIT Press.

Voeten, H.A.C.M., O.B. Egesah, M.Y. Ondiege, C.M. Varkevisser, and J.D F. Habbema. 2002. ‘Clients of female sex workers in Nyanza province, Kenya: A core group in STD/HIV transmission’. Sexually Transmitted Diseases29 (8): 444–52.

Alubo, O., S.O. Alubo, P. Patrobas, C.M. Varkevisser, and P. Lever. 2003. Gender, leprosy and leprosy control: A case study in Plateau State, Nigeria. Amsterdam: KIT Press.

Varkevisser, C.M., I. Pathmanathan, and A. Brownlee. 2003–2004.Designing and conducting health systems research projects. Amsterdam: KIT Publishers, IDRC Ottawa and Regional Office for Africa [1991].

Voeten, H.A.C.M., H.B. O'hara, J. Kusimba, J.M. Otido, J.O. Ndinya-Achola, J.J. Bwayo, C.M. Varkevisser, and J.D.F. Habbema. 2004. ‘Gender differences in health care-seeking behavior for sexually transmitted diseases: A population-based study in Nairobi, Kenya’. Sexually Transmitted Diseases31 (5): 265–72.

Burathoki, K., C.M. Varkevisser, P. Lever, M. Vink, and N. Sitaula. 2004. Gender, leprosy and leprosy control: A case study in the far West and Eastern development regions, Nepal. Amsterdam: KIT Press.

Voeten, H.A.C.M., O.B. Egesah, C.M. Varkevisser, and J.D.F. Habbema. 2007. ‘Female sex workers and unsafe sex in urban and rural Nyanza, Kenya: Regular partners may contribute more to HIV transmission than clients’. Tropical Medicine & International Health12 (2): 174–82.

Schilthuis, H.J., I. Goossens, R.J. Ligthelm, S.J. de Vlas, C. Varkevisser, and J.H. Richardus. 2007. ‘Factors determining use of pre-travel preventive health services by West African immigrants in The Netherlands’. Tropical Hygiene & International Health 12 (8): 990–98.

Varkevisser, C. 2009. ‘Primary health care: Terugblik en vooruitzicht’. In Theory and action: Essays for an anthropologist, edited by S. van der Geest and M. Tankink, 226–32. Diemen: AMB Publishers.

Varkevisser, C.M. 2010. ‘Why medical anthropology matters: Looking back on a career’. In Doing and living medical anthropology: Personal reflections, edited by R. Park and S. van der Geest, 131–44.Diemen: AMB Publishers.

Varkevisser, C.M., I. Pathmanathan, and A. Brownlee.2011. Diseño y realización de proyectos de investigación sobre Sistemas de Salud: Elaboración de la propuesta de investigación y trabajo de campo. Ottawa: IDRC. [Spanish translation of 2003–2004].

Endnotes

1 Back

André Köbben was Professor of Cultural Anthropology at the University of Amsterdam (1955–1976). In 1976 he founded the Centrum voor Maatschappelijke Tegenstellingen (Centre for Societal Conflicts) at the University of Leiden. In 1980 he became professor at the same university and in 1983 he accepted a professorship in societal conflicts at the Erasmus University in Rotterdam. He retired in 1990. More about him can be found in a collection of essays on the occasion of his retirement (Bovenkerk et al. 1990) and in an interview in Etnofoor (Verrips and Strating 2005).

2 Back

Jan van Baal (1909–1992) was governor of the Dutch colony of New Guinea (1953–1958). In 1958 he returned to the Netherlands after the colony was handed over to Indonesia and became director of the Physical and Cultural Anthropology section of the Royal Tropical Institute in Amsterdam and Professor of Anthropology at the universities of Utrecht and Amsterdam. Van Baal took an interest in cultural adaptation, school education in developing countries, and religion. After his death in 1992 a special issue of the journal Antropologische Verkenningen was devoted to his work and legacy (De Ruijter and De Wolf 1993).

3 Back

Pieter H. Streefland (1946–2008) was a sociologist of non-Western societies. After Varkevisser, he headed the primary health care section at the Royal Tropical Institute in Amsterdam. In 1990 he became Professor of Applied Development Sociology at the University of Amsterdam and a core member of the medical anthropology section. The focus of his work was the intertwinement of poverty, politics, and ill health, particularly in southern Asia and Africa. He died in 2008 after a prolonged illness at the age of sixty-one. For his obituary, see Van der Geest 2008.