In the shadow of tomorrow

Ebola vaccine research in Liberia

—

This photo essay draws on images taken by the author in Liberia between August and December 2016, as part of an anthropological project exploring the perspectives of participants involved in Ebola vaccine research at the peak of the outbreak. In 2014, a US-Liberian collaboration resulted in the launch of Liberia’s first large-scale randomized Ebola vaccine clinical trial. Fifteen hundred people were rapidly recruited to participate in the trial and subsequently found to have compliance rates of 98 percent, an achievement that researchers had previously thought unimaginable.

The initial purpose of these photographs was to document some of the spaces and objects encountered during fieldwork.[note 1] Later, I came to view these images as evocative of the ‘ethical variability’ of the trial. I use Petryna’s (2005) concept of ‘ethical variability’ to refer to situations in which normative bioethics (routine institutional ethical procedures in clinical trial research) fail to account for human subjects’ pragmatic motives to participate in such trials. The notion of ethical variability presents a sharp challenge to those who argue that ‘healthy volunteers’ participate in clinical trials out of altruism, providing free labor for science and development.

In this photo essay, I argue that for many Liberians, the decision to participate in Ebola vaccine clinical trials was embedded in historical and ongoing systems of exploitation, and was powerfully shaped by the fact that trial participation allowed them to obtain medical care and socioeconomic benefits that were otherwise out of reach. I suggest that photographs of the material and social contexts in which clinical trials unfold in Liberia and elsewhere can reveal important dynamics that are not taken into account by normative bioethics.

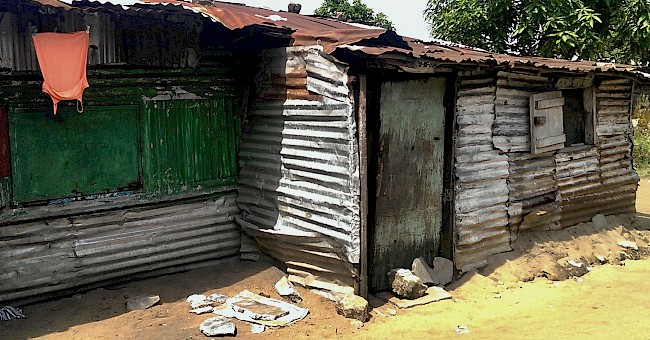

Ethical variability is produced by the social, historical, political, and economic contexts in which clinical trial research is deployed. Photograph 1 documents a community that might be seen, through the lens of normative bioethics, as having made an important, altruistic contribution to science and development by hosting Liberia’s first large-scale randomized Ebola vaccine clinical trial. Joshua, not pictured in the photograph, was a thirty-five-year-old man who lived in this community at the time of my research. He had lived through the Liberian civil wars (1989–1997, 1999–2003), and was working as a motorbike taxi driver when Ebola broke out in 2014. At that time, both his low income and his fear that he might contract Ebola from his passengers motived him to participate in the vaccine trial. For Joshua, participation was a way to protect his health and build economic capital; he hoped to receive a job supervising human subjects in upcoming trials at the conclusion of his participation. The trial gave participants a small amount of money to cover their travel to and from the site; this ‘transport compensation’ became his only source of income when his employer fired him because he feared that Joshua might become ill with Ebola from the vaccine and infect his passengers (photograph 1 shows a bike that Joshua used to ride but is now used by another driver). At the time of the trial, rumors were circulating that the vaccine research was causing the spread of Ebola, fueling stigma and discrimination towards trial participants and undermining their hopes for a better future through involvement in research. In addition to the stigma Joshua bore as a result of his affiliation with what many in the community termed ‘Ebola businesses’, he was also stigmatized as a member of ‘zogos’: a term that refers to street criminals and thugs in Liberia. In sum, Joshua’s participation in the clinical trial, like many others in the community, was not born out of volunteerism and altruism, but rather was built upon the precarity of the place where the trial research took place.

Why else was it important for precarious Liberians, like Joshua, to become human subjects in a large US-Liberian clinical research trial? Photograph 2 depicts a meeting room in the first research unit in Liberia to begin running various clinical research projects, which was referred to as ‘Little America’ by trial employees and connected to ‘Big America’ through regular videoconferences with trial sponsors and regulators. The naming of the research unit as a sort of archipelago of the United States has particular social, cultural, and economic resonances. Beginning with the establishment of the state in 1822 by American settlers and continuing into the present, privileged membership in Liberian society has long been equated with access to Western education and medicine, participating in formal employment and the cash economy, practicing Christianity, and speaking English (Utas 2003). Until the outbreak of the civil wars, wealthy Americo-Liberian families upheld a wardship system of exploitation in which people from poor areas traded their labor and compliance with the ruling class for a chance to achieve upward mobility in a highly stratified society (Dolo 2011). Little America similarly held up the promise of a better future for those who had access to this space, while at the same time harboring the risk of exploitation. Little America offered trial subjects medical care, workshops led by trial educators, and a variety of other forms of social and economic capital. It also implemented a tracking system, whereby people from the community were given some formal powers in order to facilitate compliance among trial participants. In these ways, Little America emulated the wardship system of the past. Trial subjects traded their compliance for various kinds of temporary support and hopes of upward mobility (for example, as trackers) in the expanding clinical research sector. Some trial subjects had bigger dreams: Joshua and others hoped that trial participation would eventually allow them to move to the United States. Photograph 3 reflects this dream: on a wall separating Monrovia and the Pacific Ocean, there is a painting of a Liberian driving a car somewhere in Brooklyn.

3. A wall separating Monrovia and the Pacific Ocean, featuring a painting of the Brooklyn skyline and a Liberian car driving alongside it

3. A wall separating Monrovia and the Pacific Ocean, featuring a painting of the Brooklyn skyline and a Liberian car driving alongside itWhat actually happened to people when their participation in the trial ended? Participants like Joshua received a simple paper certificate to signify their official participation in and graduation from the Little America trial. The graduation certificate materialized the quasi-professional status of trial participants. Participants’ contributions to the trial could be characterized as ‘clinical labor’, that is, as one of the many forms of labor that exist globally without labor protection (Abadie 2015; Cooper and Waldby 2014; Parry 2015). At the same time, graduation from the trial was also an intensely local experience that closely resembled the graduation ceremonies that occurred after post-civil war reintegration programs. These programs combined labor, training, and temporary financial support with the aim of reintegrating ex-combatants and community members alike into post-civil war society (Kilroy 2015). Ebola clinical trial research similarly reintegrated marginalized people, like Joshua, into the national collective. Tellingly, both post-civil war reintegration programs and the Ebola clinical research trial generated expectations that participants would be offered ongoing care and support and opportunities for upward mobility, expectations that would be disappointed upon graduation.

While Joshua hoped that his participation in Ebola clinical trial research would somehow provide a route to the kind of life depicted in the mural in photograph 3, instead, after the trial was over, he ended up spending a lot of time at home alone (photograph 4), in the neighborhood where he continued to encounter the bike that he used to ride and that allowed him to earn income. Like the other trial participants I encountered, he was disappointed that the care and support he had once accessed through the trial had stopped once the active phase of the trial was over. Right up until trial graduation, Joshua held out hope that Little America would compensate him for his struggles and the setbacks he had experienced as a result of his participation. In particular, he kept hoping that he would soon have the opportunity to enroll in other trials as a ‘responsible’ human subject with previous trial experience, or that he might become a supervisor or tracker of other human participants in upcoming Little America projects. However, none of that happened. Joshua had received the experimental vaccine, and only graduates who received the placebo or those who had never participated at all were invited to participate in next Ebola vaccine trial. Once Joshua received his graduation certificate, he refused to participate in other Little America participatory research projects for which he was eligible because he felt used, betrayed, and abandoned.

Joshua’s story is unfinished. Perhaps he decided to commit himself to those other research projects for which he was eligible. Perhaps he got his motorbike back, perhaps he is driving a car somewhere in Brooklyn. What this photo essay illustrates is the social, historical, and economic contexts that shape and constrain ‘voluntary’ decisions to participate in research, those which lie beyond the scope of normative bioethical assumptions. By subscribing to one-size-fits-all discourses, normative bioethics risks mispresenting the participatory motives of trial subjects seeking recognition and support in settings of precarity. Photography combined with ethnography can expose the ethical variability of clinical trials and offer a different view on bioethics in practice.

About the author

Arsenii Alenichev is trained as a biologist and bioethicist with a specialization in international research ethics. He is currently a PhD student affiliated with the University of Amsterdam and the Barcelona Institute for Global Health.

References

Abadie, Roberto. 2015. ‘The “Mild-Torture Economy”: Exploring the World of Professional Research Subjects and Its Ethical Implications’. Physis 25 (3): 709–28. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-73312015000300003.

Cooper, Melinda, and Catherine Waldby. 2014. Clinical Labor: Tissue Donors and Research Subjects in the Global Bioeconomy. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Dolo, Emmanuel. 2007. Ethnic Tensions in Liberia’s National Identity Crisis: Problems and Possibilities. Cherry Hill, NJ: Africana Homestead Legacy Publishers.

Kilroy, Walt. 2015. Reintegration of Ex-Combatants after Conflict: Participatory Approaches in Sierra Leone and Liberia. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Parry, Bronwyn. 2015. ‘Narratives of Neoliberalism: “Clinical Labour” in Context’. Medical Humanities 41 (1): 32–37. https://doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2014-010606.

Petryna, Adriana. 2005. ‘Ethical Variability: Drug Development and Globalizing Clinical Trials’. American Ethnologist 32 (2): 183–97. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.2005.32.2.183.

Utas, Mats. 2003. ‘Sweet Battlefields: Youth and the Liberian Civil War’. PhD diss., Uppsala University.

Endnotes

1 Back

To protect the anonymity of trial participants in the context of significant stigma surrounding Ebola, the images presented here contain no people.