Asking questions

Interviews and expertise in global health research

—

Abstract

Household surveys are part of the mix of objects, techniques, beliefs, and practices that constitute the science of global health. Households are selected for inclusion in these surveys using sampling techniques that vary based on the purpose of the exercise. For instance, cross-sectional surveys collect information on the current circumstances of or health practices within a set of households that have been selected to form a representative sample of the population of interest. Impact evaluations are another survey practice; these randomly assign a health intervention to one of two (or more) groups of households and then conduct multiple survey rounds to estimate its causal impact. All surveys use questionnaires to collect information that is numeric (for example, age), binary (‘yes’ or ‘no’ are the two response options), categorical (pick one or more from a given list of responses), or scaled (for example, on a scale of one through five, with five being the best and one being the worst, please rank the quality of health services provided). Such surveys rely on people called ‘enumerators’ to interview household members and record their responses, which are then compiled into a dataset and analysed using statistical software programs. Findings are circulated in the global health research community through presentations at academic and research institutes, policy briefs, working papers, books, and journal articles.

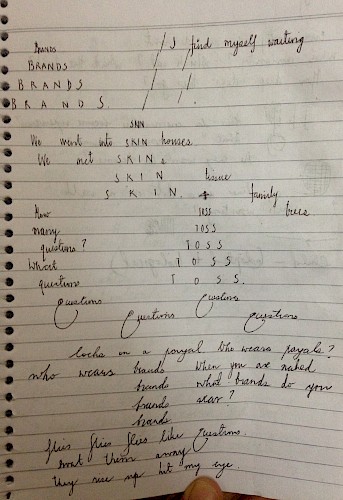

In this article, I investigate such household surveys and what they can reveal about the production of knowledge in global health, drawing upon my experience training and accompanying enumerators for a survey conducted in northern India in 2016. Following a brief overview of the methodological framework guiding this research, I summarize the survey from which the experiences recounted here are drawn. I then describe interactions among enumerators, survey respondents, and myself to illustrate how practical, social, and ethical circumstances shape the questions enumerators ask and the data they record. I argue that claims to expertise made by global health researchers often depend on their ability to overlook these contextual aspects of data collection. The arguments presented here are organized into two parts: the first describes how the enumerators’ working conditions shape the data they collect, and the second analyses how researchers use this data to make claims about research subjects. The questions I hope to shed light on are: How does the enforced intimacy of the interview encounter affect the questions enumerators ask and the responses they collect? How is the information shared by respondents and recorded by enumerators used to establish expertise in global health research?

This article follows the storytelling format employed by Pigg (2013, 128) to capture ‘the complexity of a research praxis that unfolds in and through complicated intersubjective relationships’. By foregrounding the relationships between survey respondents and enumerators, and between enumerators and researchers, I explore facets of global health that are often hidden from view but are fundamental to its practice. Unpacking the multiple meanings that global health holds for people it employs and affects allows us to understand the negotiations that give it its composite character. My goal is to add to our understanding of the conception of knowledge in global health and thereby contribute to ongoing conversations about global health’s theoretical underpinnings. My focus on praxis is motivated by a series of interrelated questions raised under the umbrella of critical global health studies, including Brada’s (2011, 287) question, ‘If so many mobilize so much behind such a thing as “global health”, isn’t it worth knowing how it is made and under what conditions?’ By studying a data collection exercise, I try to understand how the work of global health is envisioned by those responsible for producing data that sustain it. This is also a response to Adams (2016, 190), who compels us to ‘ask not only what happens to health when metrics are produced in these ways, but also what new demands are placed on those labouring in the world of global health, that is, not just those labouring under the burdens of disease and morbidity but also under the burdens of data production’.

Field practice

In June 2016 I was hired as a consultant by the World Bank to monitor and support the training of enumerators for a household survey being conducted in the North Indian state of Uttarakhand. This was the baseline survey for an impact evaluation the bank was rolling out as part of a new loan agreement being discussed with the government of Uttarakhand at the time. The evaluation was designed by experts based in New Delhi and Washington, DC, who were employed by the bank or hired by it as consultants. It aimed to evaluate the ability of certain public-private partnerships to improve access to health services for poor people and those living in remote areas. The survey covered a sample of 10,800 households spread across a hundred villages in seven districts of the state. Using a quantitative questionnaire comprised of ten modules, the survey captured information about families’ recent encounters with the health system. It covered topics such as household health expenditures, maternal and child care, treatment for chronic diseases, access to formal and informal medical care providers, and socioeconomic status. Depending on the size of the household, it could take forty-five to ninety minutes to complete an interview.

A multinational consulting group, based in the United Kingdom and with offices in India, had been hired to collect data for the baseline survey of the evaluation. To ensure good data quality in the last round of baseline data collection, four World Bank consultants were asked to monitor the training and performance of enumerators hired by the firm for this round. Training of enumerators was organized and conducted by the firm at an ashram run by a regional civil society organization in a small town in Uttarakhand. While the firm’s trainers and enumerators lived at the ashram during the training, World Bank consultants (myself included) stayed at a more expensive hotel about two hours away. We had a car at our disposal and were driven to the ashram every morning to observe and help with the training. Over roughly two weeks, at least two consultants monitored the trainings every day.

Thirteen enumerators participated in the training; they all were college students from another region of Uttarakhand. Of the thirteen, three had participated in previous rounds of this baseline survey. Most of the other ten were new to survey work and had been encouraged to participate in the training by older students in their college who had worked as enumerators for similar surveys. These new enumerators were given room and board by the consulting firm during the course of the training, with the understanding that they would be paid a daily wage once they started conducting survey interviews. Because the firm had not been able to recruit experienced enumerators to participate in this round of the survey, multiple days of mock interviews and field practice were organized. In the mock interviews, a consultant acted as the head of a household and the enumerator had to approach and interview her. For field practice, enumerators were taken to villages close to the ashram and were expected to approach and interview the head of a household. We judged enumerators on their ability to confidently approach the person to be interviewed, explain the purpose of the interview to them, and convince them to participate. This necessitated an understanding of survey sampling methods and data confidentiality. We asked enumerators to inform respondents that the information they were collecting would help the state government and the agencies supporting it evaluate health programmes that would soon be implemented. They were to also explain to respondents that information would not be traced back to them or used to alter any government services that their family was receiving. In addition, we expected enumerators to ask questions in a manner that the respondent understood and felt comfortable answering. Based on their performance, we approved six enumerators to conduct interviews for the last round of the baseline survey. Of these six, two had participated in previous survey rounds, two were studying social work at the graduate level and thus had some experience approaching poor or rural households and enquiring about their access to social services, and two had no educational or professional experience conducting household surveys apart from the training they had received in the previous two weeks. These last two were deemed suitable for conducting interviews under the supervision of more experienced enumerators or supervisors.

Fieldwork

Upon the completion of training, I joined a team of six enumerators and their supervisor in the town of Satpuli. With a guest house as their base, this team was conducting interviews in two administrative blocks of Uttarakhand’s Pauri Garhwal district. Each day they split into two groups and went to a village, or two neighbouring villages, to interview heads of select households. They left the guest house in the morning, at a time that would allow each enumerator to interview an average of six households in a day. Based on the distance of the village from Satpuli, they would return to the guest house for food and rest in the evening or at night. My task was to accompany the enumerators, observe them as they conducted interviews, and relay this information to the World Bank team. I did this for four days, and finding that the enumerators were doing what we expected them to do, I left Uttarakhand.

On my first day in Pauri, I accompanied Ramesh, a new enumerator we had helped train, to the six households he had to interview that day. In one of the houses, an eight-year-old child suffering from cerebral palsy lay on the bed and drifted in and out of sleep as Ramesh interviewed his father about his family’s experience with health services in the region. For many years, the family had been trying to get support from the government for the child, either in the form of a disability grant or care services, but had not yet been able to do so. The father seemed dejected and questioned the government’s desire to help families such as his. When Ramesh explained the purpose of the survey to him, he expressed apprehension about the usefulness of such exercises and yet cooperated by answering all our questions. As the interview progressed, the realization that this survey was not going to help his family directly, at least in the short term, hung heavy above me.

Over the next few days of fieldwork, I was repeatedly confronted by the seeming irrelevance of this survey for the families we were visiting. Often it was expressed directly by family members. Each day, an enumerator and I met at least one family that had a member suffering from a debilitating illness, the treatment of which was draining their resources. Services provided by the government – in the form of pensions, free pharmaceuticals, and Ayurvedic doctors at the closest public health centre – were deemed inadequate and the state was often presented as uncaring. Thinking about my responsibility to these families, I began to question whether the research I was helping conduct was motivated by a desire to help families in need of public services or driven by other priorities. Similar to research coordinators in other settings, I was finding it hard to reconcile research goals with the needs of research subjects (Fisher 2006).

During my last day of fieldwork, an enumerator and I met a man suffering from tuberculosis (TB). He told us that patients were left to die like animals at the government hospital he was first admitted to when he felt ill. He had received better care at the military hospital his family subsequently took him to, and was now receiving treatment under the government’s directly observed short-course treatment (DOTS) programme. Due to TB, he felt too weak to work and had stopped earning, as a result of which his family’s income had suffered. When he spoke to us, he either looked down or to his side to prevent the air emanating from his lungs from reaching us. As a result, he did not make eye contact with either the enumerator or with me almost the entire time we were with him. After about an hour of interviewing this man, the enumerator asked him – as per the requirements of the questionnaire he was responsible for completing – to ‘please imagine a ladder with steps numbered from zero at the bottom to ten at the top. The top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you and the bottom of the ladder represents the worst possible life for you’. He was then shown a black and white print of a ladder and asked, ‘On which step of the ladder would you say you personally feel you stand at this time?’ and ‘On which step do you think you will stand about five years from now?’

The cruelty of asking these questions to a man suffering from a potentially deadly disease shocked me then and it continues to rattle me today. Since leaving Uttarakhand, my unease has condensed around a question Ramesh asked me that night, once we were all back at the guest house in Satpuli. I was due to leave Uttarakhand the next morning and met the six enumerators I had been working with to thank them for their patience and commend them on their hard work. We exchanged phone numbers and promised to stay in touch. Grappling with what I had witnessed over the past few days, I asked them what they felt about conducting household surveys on access to health services in their state. Most enumerators said participating in this exercise helped them understand the problems faced by villagers. A few said the experience motivated them to help alleviate these problems. I probed further and asked them about the families they had interviewed in Pauri. Ramesh confidently answered back with the question, ‘Inke saath to mazaak ho raha hai na, ma’am?’ (Isn’t a joke being played on them, ma’am?).

Ramesh’s question

Ramesh’s question succinctly challenges the methods and practices that have come to define global health research in places like Uttarakhand. In this section, I use it to consider how the working conditions and ethical challenges faced by enumerators affect their work. In order to draw attention to how enumerators shape the data they collect, I focus on the manner in which enumerators ask questions and record responses. By describing and analysing interactions observed between enumerators and families in Uttarakhand, I hope to extend earlier research conducted in North America and sub-Saharan Africa on the position of data collectors and research coordinators in clinical trials, demographic surveillance sites, and other forms of public health research (see for example Fisher 2006; Kamuya et al. 2013).

The history of enumerative exercises conducted on the Indian subcontinent can help us contextualize the implementation of global health surveys in India today. In his historical study of enumeration in India from 1600 to 1900, Guha (2003, 154) notes that in precolonial India, ruling authorities, at the imperial and local levels, enumerated people for both fiscal and military purposes and ‘the idea of the enumerated community was widely understood’. The advent of a colonial regime and the development of demography as a discipline led to the establishment of more centralized institutions of enumeration and to an expansion in the scope of the exercise as the object of enumeration shifted from households to individuals living within them. Population censuses were undertaken by the British government in all provinces of the colony between 1868 and 1872, and the first comprehensive, synchronous census of the Indian population was conducted in 1881 (Guha 2003). This exercise has been repeated at ten-year intervals since and is ‘one of the largest administrative exercises undertaken in the world’ (Government of India n.d.). Cohn (1987) estimates that at least half a million enumerators would have been involved in the population censuses conducted in the late nineteenth century, and the Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India notes that it trained two and a half million people to act as enumerators for the 2011 census (Government of India n.d.). Census enumerators have been, and continue to be, local people with close ties to the state. In 2011, elementary school teachers employed as permanent staff in government schools acted as enumerators in rural areas, whereas teachers and officials from central, provincial, and local governments collected census data in urban areas. All of them were trained for three days and, on average, interviewed between 750 and 800 people in three weeks (Government of India n.d.).

Historical research has highlighted how the social, economic, and political backgrounds of data collectors can influence the results of enumeration exercises. For instance, in his study of the first colonial census of the state of Rajasthan in 1835, Peabody (2001) finds that native informants who acted as local enumerators played a crucial role in determining the kind of information that was collected about the state’s population and the categories into which this information was organized. Contemporary global health surveys in India share key similarities with state-sponsored enumeration exercises with regards to the role and position of enumerators in these projects. In both instances, enumerators are deployed for a short period of time to conduct a fixed number of interviews in a specific geographic location. They act as intermediaries between the enumerating agency and its population of interest but are generally not involved in the design of the enumeration exercise itself. Nor do they have a say in how the data they collect is ultimately used and disseminated. In rural areas, enumerators are drawn from a relatively small pool of literate adults and are given a few days of training to prepare them for enumeration. These similarities encourage us to consider how the social and economic circumstances of people hired to collect data for global health surveys in India today might influence the conduct and results of these surveys.

In his discussion on the employment of ‘hired hands’ in research, Roth (1966) likened the position of data collectors to that of workers in a production unit. He argued that some form of cheating or negligence in the collection or processing of research data should be expected from these workers because they have no say in the design or effects of the work they are hired to do. Subsequent research has paid closer attention to how the work of data collectors is affected by structural and situational factors, such as the terms of employment, the socioeconomic and historical context in which they work, and the ethical challenges that ensue from their close interaction with research subjects (Biruk 2011; Finn and Ranchhod 2013; Fisher 2006; Fisher et al. 2013; Kamuya et al. 2013; Kingori 2013; Kingori and Gerrets 2016; Reynolds et al. 2013; Staggenborg 1988; True, Alexander, and Richard 2011; Waller 2012).

Global health requires the translation of global methodologies and instruments, such as questionnaires, to local spaces. Enumerators play a key role in this. While the motivations for enumerators to contribute to the production of global health knowledge might seem straightforward – they are paid for each interview they conduct – the context in which they work and their position in the global health research domain shape the contributions they make. Although enumerators are assigned tasks that require the closest interaction with research subjects, their experiences and suggestions do not usually inform health policies or research agendas. Respondents address their questions and concerns to enumerators but the latter rarely get to interact with the people who fund, design, and approve the surveys they carry out. Unless it is a pilot exercise, it is unlikely that enumerators’ observations during data collection will alter the research design because most enumerators are hired after the questionnaire has been finalized. Problems encountered during data collection are considered relevant only if they are linked directly to questions listed in the questionnaire. These, when recorded, are taken into account during data analysis. Research coordinators like me are hired to ensure that enumerators ask the questions listed, and we are responsible for relaying insights from fieldwork up to our managers. While these insights are often derived from the experiences of enumerators, the voice of the enumerator itself does not ‘travel up’. Enumerators cannot pressure us to report concerns we do not deem relevant enough to pass upwards.

Of all workers involved in the production of global health research, enumerators often have the fewest years of formal education, are paid the least, and are considered easiest to replace. Their position seems to mirror that of technicians hired by English scientists in the seventeenth century; as Shapin (1989, 557) observes, ‘Though science could not be made if this work were not done, it is thought that anyone can do it, that such workers are easily interchangeable on the labor market and that no knowledge-ability and little skill are involved in its performance’. The design of the research study Ramesh and I were hired to conduct assumed that a couple of weeks were sufficient to train people on how to seek consent and conduct hour-long interviews on complex and personal topics such as income, expenditures, and medical histories. Crucially, because trainees were not paid during training, it was not in their interest to prolong training even if they felt the need. The research design also assumed that enumerators’ experience conducting interviews did not need to inform the questions they were tasked with asking. Rather, researchers expected enumerators to understand and to be able to explain to respondents the importance of each question listed in the questionnaire, if they were asked.

Enumeration is not simply the act of reading out a question and recording the response but is an interactive exercise bound by norms of social engagement. Enumerators are expected to establish a level of familiarity with respondents within a short period of time so that the latter feel comfortable answering sensitive questions. However, the artificiality inherent in the research encounter shapes the interview and leaves a trace on the data collected. One way that it does so is by altering the questions asked by enumerators so that they are no longer standardized across survey participants. As Krumpal (2013, 2035) notes, ‘If the interviewer feels uncomfortable about asking a certain question, she may skip the question entirely or deliberately change the wording of the question. Such interviewer effects may seriously distort answers to sensitive questions’. In the survey I was helping conduct, one of the older male enumerators was visibly uncomfortable asking a young mother about her current breastfeeding practices. This was because in the geographic and social space wherein the survey was being conducted, conversations about breastfeeding do not generally take place between young women and older men who are strangers. One of the ways the enumerator tried to overcome his discomfort was by changing the question’s wording, choosing not to use the word ‘stan’ (breast in Hindi) while asking the question. Instead he asked the young mother whether she fed her child ‘apna doodh’ (your milk). My point is not that he asked the incorrect question or that the response he received was different from the ‘true response’ questionnaire designers were looking for. Rather, this example illustrates enumerators’ capacity to modify questions based on situational factors. This ability is crucial for ensuring that respondents answer questions: enumerators need to ask questions in ways that do not offend or incite respondents. It seems that in translating the written question to one that can be asked, enumerators implicitly acknowledge the unsuitability of the written question to the current context. Their translation is constructed specifically for the person being interviewed and thus varies across survey participants.

Besides shaping the translation of a question, situational factors also influence how much time enumerators take to ask it. For instance, in categorical questions that allow for multiple responses, the number of responses a respondent picks may be affected by the number of times the enumerator reads out all the response categories to her and the speed at which he does so. The amount of time an enumerator is able to give to such questions is influenced by practical concerns – such as the time he has left to complete the interviews he has been assigned for the day – and social conditions that determine his rapport with the respondent. Several studies have noted the crucial role played by gender and class with regards to the latter (Blaydes and Gillum 2013). The influence of the enumerator and his circumstances on the collected data is also evident in scale questions like the one asked to the TB patient. These often require enumerators to guide respondents who are not familiar with providing numerical responses to affective questions. In explaining the question and using examples to show what a particular number on the scale could mean, the line between probing and leading the respondent to a particular response becomes blurred. In such cases, making sense of the question becomes a collaborative exercise and the enumerator’s presentation of it can seep into the respondent’s answer. The necessity of this collaboration illuminates the opaque nature of such survey questions and sheds light on the gap between research design, which assumes that all respondents are asked the same question and understand it the same way, and research practice, which depends on enumerators’ ability to explain and modify questions based on the circumstances of an interview.

The ethical challenges enumerators face while working also leave their mark on the collected data. This is because ethical considerations affect enumerators’ attitude towards research processes and participants. While researchers hope that their findings will guide policies and programmes, they cannot ensure that research subjects will directly benefit from their study. During our survey in Uttarakhand, many household members reacted with irritation when we explained the purpose of the survey to them and requested their participation. They explained that similar surveys had been conducted in their village in the recent past but had not resulted in any improvements. They questioned our argument that the state would be able to take steps towards solving their problems once it knew what those problems were. Some people agreed to be interviewed when the enumerators and I acknowledged that we needed their cooperation simply to complete the jobs we had been assigned. Compared to the uncertainty of the benefits that could accrue to families we interviewed, the benefits of this survey for those conducting it are apparent. Research coordinators like me, enumerators, supervisors, and other employees of the consulting firm and the World Bank were all paid for our involvement in this exercise. Funders, who own the collected information, use it to showcase their knowledge about health services in an area. Project managers share survey results with concerned governmental agencies and use the data to advance discussions about aid. Researchers publish findings – which sometimes compare findings from other geographical areas –and gain professional recognition within the global health research community through their use of this data. In this way, the information shared by families, when converted into a dataset, becomes a form of capital. Janes and Corbett (2009, 176) discuss how this export of information recalls a new form of colonialism by ‘extending uses of sites in the global south to study their disease burdens to satisfy the needs of science … to find new subjects and explore new problems’. They acknowledge that this manner of knowledge creation and exchange in the field of global health can be unfair and ethically problematic.

Enumerators witness the inequitable nature of global health research during their day-to-day work. Their close interaction with respondents and their geographic and socioeconomic distance from senior researchers can make them feel more connected to research subjects than to the research team (True, Alexander, and Richard 2011). As Kingori and Gerrets (2016) illustrate, the ensuing moral challenges can lead to data fabrication and deviation from research protocols when coupled with difficult working conditions and a hierarchical division of labour that does not provide room for data collectors’ concerns to inform the research process. These deviations can substantially affect research findings (Finn and Ranchhod 2013). The position of enumerators as intermediaries between research subjects and institutions can also lead enumerators to develop an expectation that participants’ contribution to the success of a study be reciprocated in a way that is meaningful to them (Reynolds et al. 2013). In the survey Ramesh and I were conducting, enumerators used a variety of methods to convince people to participate in research: they spoke about the importance of the survey and its potential benefits, mentioned the backing of the state, pleaded, and sometimes deliberately underestimated the time an interview would take (for example, saying an interview would last thirty minutes when it was likely to last an hour). These techniques were used to convince potential respondents that their time and effort in sharing information would be compensated, either in the form of improved services or the enumerator’s well-wishes. Enumerators thereby took on the ethical labour of convincing participants that they would benefit in some way by participating in the research.

Ramesh’s question taps into the frustration enumerators can feel when working in highly inequitable research contexts and finding themselves unable to use resources made available for research to help respondents asking for assistance. I would argue that conducting interviews for quantitative surveys among poor people about sensitive topics can prod those who are doing the questioning to view their respondents as powerless beings in need of help. Given the speed and movement that have come to characterize global health activities, enumerators hired on short-term contracts and conducting cross-sectional surveys are tasked with collecting specific information within a limited period of time from people they are unlikely to meet again. This ensures that they often lack information about the broader context of a respondent’s life, including her motivations for participating in a research study. Enumerators’ conception of such research subjects as people being manipulated and taken advantage of by local and global institutions can make them critical of the research process. In response, they might skip questions they feel could embarrass or unnecessarily burden respondents (Kingori 2013).

Other actions that might result from enumerators’ desire to help respondents, or at least not burden them further, include efforts to cheer them up by encouraging them to be optimistic about the present or future. Such efforts can also affect research results. The twin questions that ended the questionnaire we were fielding in Uttarakhand illustrate this point. While asking about which rung of the ten-step ladder respondents felt their household stood on currently and expected to be standing on five years down the line, a couple of young enumerators I observed subtly encouraged respondents to pick a higher number for the second question than they had picked for the first. For instance, in a household we visited in a remote village in Pauri, the respondent was a father of three who lived with his children and wife in a small mud hut. He worked as a daily wage labourer but recently had been having difficulties working regularly due to an injury. When asked about the ladder, the respondent picked the same low number for both questions, saying he didn’t expect his family’s situation to improve in the near future. The enumerator asked him if he was sure about this. When he assured us that he was, the enumerator pointed out to him that his young children – who were sitting on the bed with their father and had listened in on the whole interview, at times helping him answer questions about their education and health – were going to school and would thus attain a higher educational status than their parents. Might this not positively affect the family’s situation in the coming years? The respondent wasn’t sure and hesitated to change his answer. As the enumerator and respondent continued their conversation, however, the respondent’s eldest child, a young girl between ten and twelve years of age, scooted towards the printout of the ladder that the enumerator was holding out to her father and with a shy smile put her finger on a higher number than the one her father had initially picked. Everyone present in the hut, including the child’s parents, laughed. The enumerator asked the question again and this time the respondent chose the number his daughter had picked. This was recorded as the household’s answer even though, contrary to research protocol, it was not the answer initially given by the head of the household. Upon observing multiple encounters such as this one, I came to regard enumerators’ efforts to deliberately end some interviews on a positive note as a way for them to give something back to families with whom they had spent an hour talking about meaningful and private topics such as births, deaths, illnesses, and incomes. Such efforts allowed enumerators to see their work as a beneficial exchange rather than an extractive exercise.

Establishing expertise

Building on Roth’s discussion on how a hired-hand mentality affects research outputs, Staggenborg (1988) emphasizes the need to differentiate between different kinds of hired hands. Both workers and researchers are employed to perform specific research tasks. However, while the former do not have an interest in social research or academic careers, the latter do. My participation in this research study was motivated by a desire to strengthen my credentials as a public health researcher. On the other hand, Ramesh entered the pool of possible enumerators for this study because he was encouraged by his elder sister and older friends to try out enumeration as a means to earn some income and explore career paths while staying close to home; he did not intend to build a career in research. Similarly, structural factors such as research funding and study duration affected us differently. While I was paid for each day I was in Uttarakhand, Ramesh and other enumerators were not. These differences shaped how we approached our work, what we felt about the research process, the conclusions we drew from our experiences, and how we used the same. As illustrated above, the data collected by enumerators was shaped by the context of an interview and their conception of the respondent. These factors determined the way they asked questions, the responses they recorded, and which aspects of the research protocol they followed or disregarded during a given interview. Global health researchers create knowledge products – at least in part – to establish expertise, which depends on their ability to emphasize or disregard certain aspects of research practice. This ability is in turn affected by the material aspects of their research.

To explain the way expertise comes into play in research settings, I must begin by analysing my reasons for writing this article. So far, I have argued that it is important to pay attention to aspects of data collection that are not covered by the instructions, questions, and translations printed on a questionnaire. By placing value on these aspects, I have also conferred value on my witnessing of them. I am thereby using my spatial proximity to enumerators and respondents – a result of my relatively low position in the hierarchy of global health research – as a stepping stone to present myself as a thoughtful intellectual who holds valuable knowledge about the research process. As Carr (2010, 19) finds, ‘people become experts not simply by forming familiar – if asymmetrical –relationships with people and things, but rather by learning to communicate that familiarity from an authoritative angle’. In writing this article, I am laying claim to the possession of expert knowledge. In line with Dumit’s notion of ‘expert objects’, I am doing so by presenting enumerators as objects that require special knowledge to be understood (Dumit quoted in Carr 2010). I am also casting myself as an expert by differentiating my knowledge from that of other researchers involved in this survey. This is in line with Carr’s (2010, 22) argument that ‘realizing one’s self as an expert can hinge on casting other people as less aware, knowing, or knowledgeable. Indeed, expertise emerges in the hoary intersection of claims about types of people, and the relative knowledge they contain and control, and claims about differentially knowable types of things’.

While my claim to expertise is based on aspects of the survey I was granted access to, other researchers studying this impact evaluation may use different resources to establish their expertise. Researchers responsible for making scientific claims about the population of interest may base their expertise on the collected data and in ‘unknowing’ those features of survey interviews that are not captured in it (Geissler 2013). This unknowing is crucial to the production of global health knowledge. Adapting Michael Taussig’s concept of ‘public secrets’ to transnational health research, Geissler (2013, 14) describes how ‘as a countercurrent to the scientific project of making the unknown known – rendering a dangerous landscape of disease legible and navigable – certain facts about the world, including vital inequalities, are here made “unknown” or rather, handled … as “public secrets”’. He illustrates how material inequalities among research staff and between research workers and participants contribute to the successful production of scientific knowledge but are not discussed in scientific texts or public debates because doing so might ‘raise regulatory concerns and potential disciplinary action, rupturing the collaborative texture [of research projects] and possibly causing moral unease’ (Geissler 2013, 21). These concerns also ensure that the social and ethical undercurrents that run through survey interviews and shape the collected data are not generally acknowledged in knowledge products created for the global health research community. Like material inequalities, inequalities in the distribution of benefits and burdens that result from research are felt and experienced but not considered crucial to the quality of research findings. Unknowing them is necessary for the production of global health knowledge because publicly recognizing them leads one to question the legitimacy of the survey, both in terms of the reliability of data produced and the motivations driving the exercise in the first place. Thus, to circumvent these questions and continue the production of global health research, ‘both unknowing and knowledge are critical to the practical conduct of everyday research practices’ (Geissler 2013, 23).

The spatial and geographic dimensions of research also influence the construction of health expertise (Erikson 2011; Harper 2011). In this article, I have presented myself as an expert by claiming that the geographic distance separating researchers in New Delhi and Washington, DC, from enumerators and respondents in Pauri opens a gap between research design and practice. I have used this gap to shed light on the subjective and contextual nature of data, and to question the ability of quantitative survey methods to represent an objective reality. On the other hand, the expertise of quantitative researchers relies on the survey questionnaire being a physical boundary that separates subjective experience from objective information. Researchers are able to diagnose the health problems faced by a population because the questionnaire is designed to collect only and all the information necessary to calculate such statistics. In this way, the physical aspects of our respective epistemologies determine how we gather information and shape our claims to expert knowledge.

Conclusion

This article originated from moments of unease during fieldwork that compelled me to think more deeply about what transpires during a survey interview. I hope the discussion presented above sheds light on the processes that shape the creation of global health knowledge, and that it shows that the acts of asking, listening, and reporting are not dispassionate exercises. Rather, they are motivated, consciously and subconsciously, by aspects of the survey that fall beyond research design and protocols. Enumerators alter survey questions to suit situational circumstances and to elicit narratives about illness, treatment, kinship, etc. They have to disregard parts of these narratives that cannot be incorporated as numeric or categorical responses to survey questions and they also disregard instructions given in the research protocol that could hinder their relationship with respondents. Enumerators’ conception of respondents is thus framed by the questions they are tasked with asking, the limited time they spend with them, their consequent inability to understand the broader context behind respondents’ participation, and the ethical dilemmas they face as a result of this work. These aspects of an interview shape the responses an enumerator expects, receives, and records as data. As researchers go about analysing this data to produce scientific evidence about the research population, acknowledging or ‘unknowing’ certain aspects of data collection allows them to claim expertise and assert their position as holders of knowledge.

Understanding the processes that create global health knowledge allows us to see the multiple functions this knowledge serves. For enumerators and researchers, household surveys are a source of income. The production of global health knowledge thus helps sustain livelihoods. Similarly, it helps sustain engagements between research experts, funders, and policy makers who approve the research. The knowledge produced through global health research efforts enables researchers to present themselves as intermediaries between policy makers and subjects. Overall, it seems that this knowledge fulfils various purposes while it is being produced, before it even reaches the possibility of influencing local and global health policies. A theme that emerges from this analysis is the ability of this form of knowledge production to support the sustenance of certain pre-existing identities and relationships. Delineating the constituencies and functions served by the production of global health knowledge thus helps direct our attention to the ecology of actors and institutions that global health research supports and depends upon.

In this article, I have tried to shed light on the micropolitics that undergird the practice of global health research, using the figure of the enumerator to complicate Janes and Corbett’s (2009, 174) argument that ‘the global circulation of expert knowledge produces particular relations of power between policy makers and policy subjects’. I suggest that in order to understand how this power is produced and exercised we need to pay attention to the actors linking these groups and we need to study how they construct knowledge and expertise. This article is thus an effort at ‘peopling’ global health (Biehl and Petryna 2014, 376). By giving import to actors, stories, and moments that are typically considered inconsequential, I have tried to ‘render visible the messy practicalities of our ethical commitments, the hidden architectures of our desire for engagement, and the effects both of these have in global health’ (Adams 2016, 192). Engaging with the practical, administrative, day-to-day doing of global health is one way of learning how the machine works. It can help us understand how its hidden and exposed components interact to enable its functioning.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dwai Banerjee, Matthew Birkinshaw, Thomas Crowley, James L.A. Webb Jr., Seth Ligo, Swati Puri, Bhrigupati Singh, and MAT’s editorial team and anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and questions.

About the author

katyayni seth is a first year PhD student in the Department of Anthropology at Brown University.

References

Adams, Vincanne. 2016. ‘What Is Critical Global Health?’ Medicine Anthropology Theory 3 (2): 186–97. https://doi.org/10.17157/mat.3.2.429.

Biehl, João, and Adriana Petryna. 2014. ‘Peopling Global Health’. Saúde e Sociedade 23 (2): 376–89. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-12902014000200003.

Biruk, Crystal. 2011. ‘Seeing Like a Research Project: Producing “High-Quality Data” in AIDS Research in Malawi’. Medical Anthropology 31 (4): 347–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2011.631960.

Blaydes, Lisa, and Rachel M. Gillum. 2013. ‘Religiosity-of-Interviewer Effects: Assessing the Impact of Veiled Enumerators on Survey Response in Egypt’. Politics and Religion 6 (3): 459–82. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048312000557.

Brada, Betsey. 2011. ‘“Not Here”: Making the Spaces and Subjects of “Global Health” in Botswana’. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 35 (2): 285–312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-011-9209-z.

Carr, E. Summerson. 2010. ‘Enactments of Expertise’. Annual Review of Anthropology 39 (1): 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.012809.104948.

Cohn, Bernard S. 1987. ‘The Census, Social Structure and Objectification in South Asia’. In An Anthropologist among the Historians and Other Essays, 224–54. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Erikson, Susan L. 2011. ‘Global Health Business: The Production and Performativity of Statistics in Sierra Leonne and Germany’. Medical Anthropology 31: 367–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2011.621908.

Finn, Ardon, and Vimal Ranchhod. 2013. ‘Genuine Fakes: The Prevalence and Implications of Fieldworker Fraud in a Large South African Survey’. Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit Working Paper Series 115. Cape Town: SALDRU, University of Cape Town.

Fisher, Celia B., Gala True, Leslie Alexander, and Adam L. Fried. 2013. ‘Moral Stress, Moral Practice, and Ethical Climate in Community-Based Drug-Use Research: Views from the Front Line’. AJOB Primary Research 4 (3): 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/21507716.2013.806969.

Fisher, Jill A. 2006. ‘Co-ordinating “Ethical” Clinical Trials: The Role of Research Coordinators in the Contract Research Industry’. Sociology of Health & Illness 28 (6): 678–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2006.00536.x.

Geissler, Paul W. 2013. ‘Public Secrets in Public Health: Knowing Not to Know While Making Scientific Knowledge’. American Ethnologist 40 (1): 13–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12002.

Government of India. n.d. Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India.New Delhi: Ministry of Home Affairs. http://censusindia.gov.inh. Accessed on 12 October 2018.

Guha, Sumit. 2003. ‘The Politics of Identity and Enumeration in India c. 1600–1900’. Comparative Studies in Society and History 45 (1): 148–67.

Harper, Ian. 2011. ‘World Health and Nepal: Producing Internationals, Healthy Citizenship and the Cosmopolitan’. In Adventures in Aidland: The Anthropology of Professionals in International Development, edited by David Mosse, 123–38. New York: Berghahn Books.

Janes, Craig R., and Kitty Corbett. 2009. ‘Anthropology and Global Health’. Annual Review of Anthropology 38 (1): 167–83. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-091908-164314.

Kamuya, Dorcas, Sally Theobald, Patrick Munywoki, Dorothy Koech, Wenzel Geissler, and Sassy Molyneux. 2013. ‘Evolving Friendships and Shifting Ethical Dilemmas: Fieldworkers’ Experiences in a Short Term Community Based Study in Kenya’. Developing World Bioethics 13 (1): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/dewb.12009.

Kingori, Patricia. 2013. ‘Experiencing Everyday Ethics in Context: Frontline Data Collectors Perspectives and Practices of Bioethics’. SocialScience & Medicine 98: 361–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.10.013.

Kingori, Patricia, and René Gerrets. 2016. ‘Morals, Morale and Motivations in Data Fabrication: Medical Research Fieldworkers Views and Practices in Two Sub-Saharan African Contexts’. Social Science & Medicine 166: 150–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.08.019.

Krumpal, Ivar. 2013. ‘Determinants of Social Desirability Bias in Sensitive Surveys: A Literature Review’. Quality & Quantity 47 (4): 2025–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-011-9640-9.

Peabody, Norbert. 2001. ‘Cents, Sense, Census: Human Inventories in Late Precolonial and Early Colonial India’. Comparative Studies in Society and History 43 (4): 819–50.

Pigg, Stacy Leigh. 2013. ‘On Sitting and Doing: Ethnography as Action in Global Health’. Social Science & Medicine 99: 127–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.07.018.

Reynolds, Lindsey, Thomas Cousins, Marie-Louise Newell, and John Imrie. 2013. ‘The Social Dynamics of Consent and Refusal in HIV Surveillance in Rural South Africa’. Social Science & Medicine 77: 118–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.015.

Roth, Julius A. 1966. ‘Hired Hand Research’. The American Sociologist 1 (4): 190–96.

Shapin, Steven. 1989. ‘The Invisible Technician’. American Scientist 77 (6): 554–63.

Staggenborg, Susanne. 1988. ‘“Hired Hand Research” Revisited’. The American Sociologist 1 (3): 260–69.

True, Gala, Leslie B. Alexander, and Kenneth A. Richard. 2011. ‘Misbehaviors of Front-line Research Personnel and the Integrity of Community-based Research’. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics 6 (2): 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1525/jer.2011.6.2.3.

Waller, George. 2012. ‘Interviewing the Surveyors: Factors which Contribute to Questionnaire Falsification (Curbstoning) among Jamaican Field Surveyors’. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 16 (2): 155–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2012.687560.