SICK

The deadly logic of the limited good

—

Abstract

Editor’s note: click on images to enlarge or watch as slideshow.

1. A medical assistant in highland Guatemala looks back at me as my son is wheeled to surgery. Photo credit: Andrew Roper.

1. A medical assistant in highland Guatemala looks back at me as my son is wheeled to surgery. Photo credit: Andrew Roper.Jakelin Ameí Rosmery Caal Maquín was born just after my first son, close enough that her mother and I must have been in labor at the same time. Seven years later, shortly after Jakelin’s birthday, she died far from home. She had just crossed into the United States from Mexico at one of the border’s most remote ports of entry with a large group, including her father. When they were apprehended by border patrol they surrendered. Within hours, Jakelin’s temperature soared to 40.9 degrees Celsius (Hugo 2018). On a transport bus to a larger station, she vomited and became unconscious. Emergency medical technicians revived her but could not keep her alive (Holpuch 2018).

On Christmas Eve, 2018, the day Jakelin’s body was returned to her grieving mother in Guatemala, another Guatemalan child died in border custody. Felipe Gómez Alonzo was eight years old. Official US policy states that even adults should be released from holding facilities, which are often cold and uncomfortable, within seventy-two hours, but Felipe had spent nearly a week moving between holding cells with his father (Mark 2018). In the middle of the day, on 24 December, he was evaluated for ‘glossy eyes’ and prescribed antibiotics and ibuprofen. His chart said he had a common cold. He was released to a cell and many hours later, around 5 pm, someone brought him the medicine. Shortly afterward he began to vomit. By midnight, while my sons were curled up safely in their warm beds dreaming of Santa, he was dead (US Department of Homeland Security 2018).

2. My son and me in the hospital recovery room, the day after his accident. Photo credit: Andrew Roper.

2. My son and me in the hospital recovery room, the day after his accident. Photo credit: Andrew Roper.Both of my sons, now ages four and seven, have been sick in Guatemala. Coughs, rashes, the flu, and worse. Kind men and women have made them tea for upset stomachs or brought them damp cloths for their fevers. When my younger son was one, he had an accident, falling down our apartment stairs. He knocked out his teeth, crushed his lower jaw, and needed surgery. Guatemalans we barely knew ushered us to the hospital. While we were there, people checked in with us frequently to make sure we had everything they could provide. One man whose name I never learned saw me with my older child in the waiting room and brought me food from the cafeteria, knowing that even the trip across the building would be hard for me to make. Strangers came out of nowhere to see how they could help.

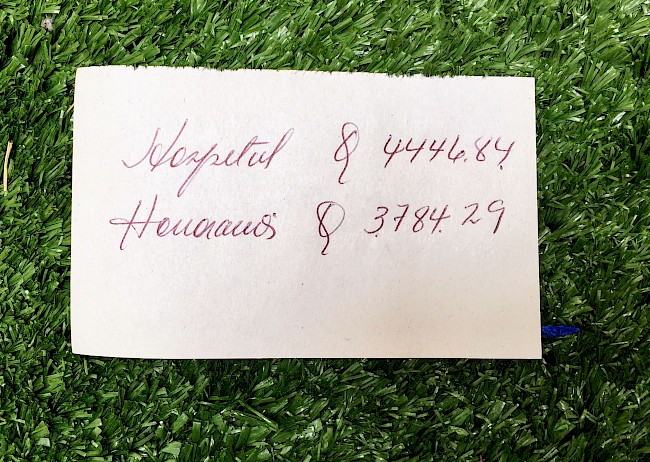

3. The entire bill, divided between hospital costs and surgery costs, and handwritten on a piece of paper, came to just over US$1,000. Photo by the author.

3. The entire bill, divided between hospital costs and surgery costs, and handwritten on a piece of paper, came to just over US$1,000. Photo by the author.Our bill for two days in the hospital, intensive care, X-rays, doctor’s evaluations, surgery, and our meals came to just over US$1,000. It’s not an inconsequential amount of money but it would not bankrupt us: better still, every cent of this bill was paid by our Dutch health insurance. This is one inequity at play: some families are destroyed by debt or death when kids get sick, while others are not. Another inequity happens well before the hospital.

4. We travel between countries by airplane, where roundtrip tickets are as low as US$300. Guatemalan children must take the dangerous and difficult land route between countries, and the expenses for this passage cost roughly US$10,000. Photo by the author.

4. We travel between countries by airplane, where roundtrip tickets are as low as US$300. Guatemalan children must take the dangerous and difficult land route between countries, and the expenses for this passage cost roughly US$10,000. Photo by the author.Consider our border crossings. Because my sons are US citizens they do not need to apply in advance for a visa to visit Guatemala. They were not born in the United States, but for them – for their chunky little white bodies – this does not matter. Their passage costs a couple hundred dollars, not the thousands of dollars that Guatemalans will pay to travel north. We present their passports upon arrival, and everyone is so kind I do not even think of this as a checkpoint. They are quickly welcomed into Guatemala and allowed to stay for months.

Guatemalan children arriving at the US border face a different reality. Applying for a visa to visit the United States from Guatemala is expensive and, unless families are very rich, the application will be denied. As a result, children are smuggled across Mexico, walking for long and uncertain days on bruised and calloused feet to desolate or disorganized points of entry. Upon arrival, their pleas to enter are typically rejected.

The causes of death for Jakelin and Felipe are disputed (Valverde 2019). Hospital records point to dehydration and the flu. Both fathers signed government-issued forms shortly before their deaths saying the children were healthy, but these only exist in English or Spanish; Jackelin’s father speaks Q’eqchi’ and Felipe’s father speaks Chuj, two of Guatemala’s twenty-one Mayan languages. When looking to determine the cause of death, Francisco Cantú, a former border patrol official, points to a widespread and encouraged culture of cruelty. He writes, ‘What happened to Jakelin is not an aberration, but rather the predictable outgrowth of the dehumanizing practices that define US border policy’ (Cantú 2018). He knows what he’s talking about, having worked for the agency between 2008 and 2012, where he was trained to pour water down the drain in front of thirsty survivors.

6. Consuela Guerra Xícara holds my son at her house in the state of Quetzaltenango, Guatemala. Photo by the author.

6. Consuela Guerra Xícara holds my son at her house in the state of Quetzaltenango, Guatemala. Photo by the author.After Jakelin’s death, Department of Homeland Security Director Kristjen Nielsen pointed to her parents: ‘This family chose to cross illegally’, she said in a television interview, although this is not true. It is beside the point that Jakelin crossed at a deliberately understaffed point of entry, where registering her large group was impossible (Isacson, Meyer, and Hite 2018). It does not matter where one crosses. Seeking asylum is a legal right, protected by US and international law (Schlein 2018).

The number of unauthorized border crossers into the United States is far lower now than in previous decades (Ward and Singhvi 2019), but the number of families entering the United States has grown tremendously in recent years (Jordan 2018). The violence and poverty in Central America has been widely reported, but here is a sobering statistic: for every child under five who dies in the United States, four children in Guatemala will die (World Bank 2017; USAID 2019). K’iche’-Maya anthropologist Irma Alicia Velásquez Nimatuj (2018) notes that Guatemala has seven public hospitals for its seventeen million inhabitants, each one in deplorable condition. Its ministry of health operates on a meager budget. She notes that specialized doctors survive on less than US$500 per month, while the presence of pharmaceutical companies grows larger and larger (Velásquez Nimatuj 2018).

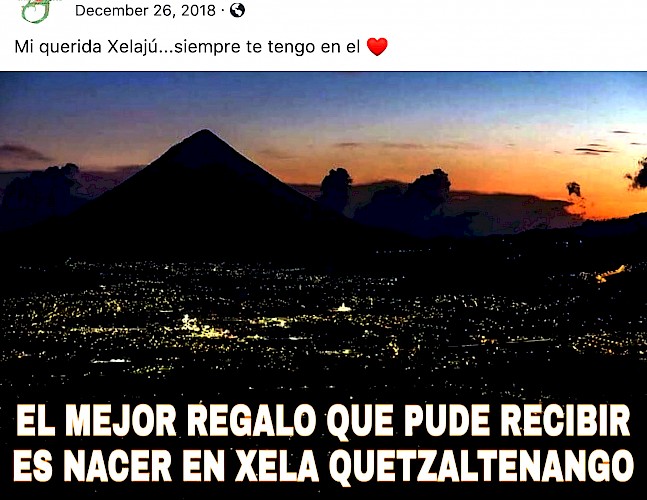

The day after Christmas, a K’iche’ friend of mine posted a message on social media that read, ‘The best present I could get is to be born in Xela Quetzaltenango’. This isn’t unusual: Guatemalans I know care deeply about their land and their languages. They do not desire to live and work elsewhere. But they also live in a country where violent crime, including the targeted assassination of Indigenous leaders, is infrequently prosecuted (Dudley 2017; Martin 2019), and where poverty has a stranglehold on Indigenous children, upwards of 70 percent of whom are chronically malnourished (Miller 2011; Yates-Doerr 2018). They live in a country that consistently ranks in the top ten of countries vulnerable to ever-escalating consequences of climate change (Kreft, Eckstein, and Melchior 2016), where coffee is being ravaged by a rust blight that is expected to intensify and that is linked to global warming (Renton 2014). They run from a deep history of Indigenous genocide and foreign intervention that has routinely trammeled efforts to build democracy and alleviate poverty. They run to the monster that is the US border, knowing of the peril but with the hope that fleeing will allow them to survive.

7. The day after Christmas a Guatemalan friend recirculated a post celebrating Guatemala. It reads, ‘The best gift I could get is to be born in Xela, Quetzaltenango’. Screenshot by the author.

7. The day after Christmas a Guatemalan friend recirculated a post celebrating Guatemala. It reads, ‘The best gift I could get is to be born in Xela, Quetzaltenango’. Screenshot by the author.US politicians allege that Guatemalan parents use their children to shield them from danger. In a recent speech encouraging the expansion of border security, Trump declared: ‘These children are used as human pawns’ (Kiely et al. 2019).

The words of Somali-British poet Warsan Shire (2011) offer a powerful response: ‘No one puts their children in a boat unless the water is safer than land’,she writes. To think these parents – or any parents – do not care desperately about their babies is to think they are not human. Which is, of course, a cornerstone of the Trump administration, which rose to political power on a platform that frequently described Latinx people in the United States as animals.

Scientific research is clear on the fact that immigration can boost economic growth and that immigrants to the United States are more law-abiding than US-born citizens (see Enchautegui 2015). Geographer Elizabeth Oglesby (2019) documents how Central Americans living in the United States have drawn on extensive expertise gained in their home countries to make the United States a safer place for its workers.

Meanwhile, Trump is known for agitating his audiences with racist, anti-immigrant language. In a speech from 2015, Trump said this about immigrants: ‘They’re taking our jobs. They’re taking our manufacturing jobs. They’re taking our money. They’re killing us’ (quoted in Kohn 2016). His 2018 Homeland Security Report was titled, We Must Secure the Border and Build the Wall to Make America Safe Again. The resonance between this title and the fourteen words[note 1] understood as a white supremacist manifesto was immediately evident to many. More recently, the US government was partially shut down for thirty-five days over a desire to build a wall whose purpose was never protection but political theater. The crowd surrounding Trump is so fixated on hate that they would rather set their own house on fire than open their doors to exhausted children begging to come in.

9. Daniela walks with my son to the city’s central park. Daniela holds his hand so he is safe from traffic on the busy streets. Photo by the author.

9. Daniela walks with my son to the city’s central park. Daniela holds his hand so he is safe from traffic on the busy streets. Photo by the author.George Foster, a US anthropologist commonly held to be the founding figure of medical anthropology, wrote about ‘the image of the limited good’ (see Foster 1965). He drew on fieldwork with Indigenous communities in central Mexico in the 1960s to document the beliefs of ‘peasants’ (a term widely dismissed today for its racist connotations). He theorized that they believed that desirable things in life had fixed limits. Health. Wealth. Status. Power. Safety. Love. Each, he argued, was understood to exist in finite quantity. Because they were always in short supply, an individual or a family could improve their position only at the expense of others. One person’s gain was necessarily another person’s loss.

I did not work at the same time as Foster, but I have not seen this kind of economic calculus among Indigenous Maya communities in the twenty years I have been carrying out fieldwork in highland Guatemala.

Caught in a sudden rainstorm with my two-year-old on a visit to one of Guatemala’s poorest hamlets, a Mam woman pulled us into her home and made us scrambled eggs and French fries while the thunderclouds passed overhead. She dismissed my attempts to offer her anything in return. While traveling through the mountains to an unfamiliar city, the bus I was riding broke down and did not reach its destination until late at night. A kind K’iche’ couple was concerned about me traveling alone in the dark and offered me a room in their house for the night. The bed was soft, the food was good, and I ended up staying two weeks.

I could continue on with other examples for some time. These are not isolated incidents. It is the case that my family moves through Guatemala with privileges of skin color and passports (among other things), which influence the hospitality we are afforded. It is also the case that mothers in the communities where I’ve worked without these privileges routinely treat each other with kindness and concern as well. That both are true – that generosity is possible – challenges the logic of Foster’s cold, determinant reductionism. Relationships in this region are not governed by a zero-sum game.

11. Consuela Guerra and Carlos Xícara play with my children in their bedroom in highland Guatemala. On our return trip to Guatemala following my son’s accident they made room in their home for us to stay with them. They spent many hours playing with my children, ensuring they were happy and safe. Photo by the author.

11. Consuela Guerra and Carlos Xícara play with my children in their bedroom in highland Guatemala. On our return trip to Guatemala following my son’s accident they made room in their home for us to stay with them. They spent many hours playing with my children, ensuring they were happy and safe. Photo by the author.It is not Indigenous communities who adhere to the image of the limited good. Instead, the people who disseminate this image are upper class and White. The image of the limited good is a lie they peddle to keep the people who listen to them angry and scared. It is a sick, cancerous image, one that feeds upon the fear of the limit to grow.

Meanwhile, the women I know in highland Guatemala care for their families and their neighbors. For them, caring for one person does not mean harming someone else. Instead, they work to make things better, knowing sickness often spreads. When we are in Guatemala and my kids get sick, I invariably return home at the end of the day with bundles of herbs and vegetables, gifts whose only return is that my children will soon get well.

Sometimes I lie awake at night after I have put my sons to bed and I miss them, although they are only in the other room. I think of their beautiful pudgy cheeks, their chubby bellies, and the mischievous glimmer in their eyes when they know they are naughty. If my children died I would never recover. I feel this raw vulnerability about other children as well. My great-grandma lost a baby, a boy who would have been my grandma’s younger brother. They lived on a wheat farm in the southwest of the United States, some distance from medical care, and he was born sickly and did not survive. It was common then, but no less painful than today. The death haunted my great-grandmother, shaping everything about my grandma’s upbringing, which eventually shaped how she raised her children, and onward down to me. A century later, I am writing about his death.

What is happening to Guatemalan children now will similarly ripple outward for generations. Lifetimes from now, the deaths of Jakelin Ameí Rosmery Caal Maquín and Felipe Gómez Alonzo will be mourned. They could have been cared for – fed, brought clean clothes and warm tea, given soft beds to sleep on, welcomed – but they were not. Their sickness and vulnerability became grounds for uncaring, for rejection. Now they are gone.

I feel despair about their deaths, and, more broadly, about the enormity of the structural forces of racism and hate that orchestrate Indigenous children’s deaths at the US border. But despair is a poor motivator toward political action. It does not tend to enable an ability to respond, to see need in others and think: ‘we have responsibility here’. So let me instead end with a message about another kind of good: a good of abundance, a good that reassures us that we have enough, there is enough.

These days, as racist lies about immigrants stealing jobs and harming lives props up the argument for a border wall, I find myself inadvertently humming a version of a joyful child’s song that my parents sang to me when I was small. It may seem inappropriate to speak of children’s music when beholding the specter of cruelty and violence. But songs for children can turn accepted logics inside out and stir our imaginations in generative ways. This song was sung by singer/activist Malvina Reynolds, a daughter of Jewish immigrants. It is about love, and as a general political ambition ‘love’ unsettles me. Too often love is the kind of kinship-love that encourages fidelity to sameness, a high price for people who are not like me. But the song is about love and magic, and its message is a good one, especially for my little White sons who must learn how to share:

Love is something if we give it away, give it away, give it away.

Love is something if we give it away, we end up having more.

It’s just like a magic penny: hold it tight and we won’t have any.

Lend it spend it and we’ll have so many,

they’ll roll all over the floor.

The song continues, refusing the image of the limited good. It holds a vital lesson for undoing national politics today, trading austerity and loss for abundance and generosity: ‘It’s a treasure and we’ll never lose it. Unless we lock up the door’.

13. Consuela Guerra and Carlos Xícara say goodbye to my son as we head to a trip to country’s capital. Photo by the author.

13. Consuela Guerra and Carlos Xícara say goodbye to my son as we head to a trip to country’s capital. Photo by the author.Acknowledgements

My recent research in Guatemala has been generously funded by a Veni Grant (#016.158.020) from the Dutch Science Foundation and the European Research Council ‘Futurehealth’ Grant (#759414). I thank Rosario García Meza, Cari Maes, Maria Garcia Maldonado, Glenda Lopez, Kim Sigmund, Andie Thompson, and Mercedes Duff for their feedback on the content of this article, and Joan Gross, whose comments inspired me to write it. I thank MATeditors Liz Cartwright, Erin Martineau, and Sarita Jarmack for their care throughout its production. My deepest gratitude goes to the countless Guatemalans who have welcomed me and my family into their country.

About the author

Emily Yates-Doerr is an anthropologist at Oregon State University and the University of Amsterdam, where she is the principal investigator of a European Research Council research project titled, ‘Global Future Health: A Multisited Ethnography of an Adaptive Intervention’ (http://www.uva.nl/en/profile/y/a/e.j.f.yates-doerr/e.j.f.yates-doerr.html). She has carried out ethnographic research in Guatemala over the past twenty years. Other publications in Medicine Anthropology Theory include ‘Translational competency: On the role of culture in obesity interventions’ and ‘Mushroom worlds and Earth beings: A resurgence of postrepresentational anthropology’. You can follow Emily on Twitter at @eyatesd.

References

Cantú, Francisco. 2018. ‘7-year-old Jakelin Caal Maquin Died at the Border. What Happened to Her Is Not an Aberration’. Los Angeles Times, 18 December. https://www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-oe-cantu-border-patrol-cruelty-20181218-story.html.

Dudley, Steven. 2017. ‘Homicides in Guatemala: Analyzing the Data’. Insight Crime, 20April. https://www.insightcrime.org/investigations/homicides-in-guatemala-analyzing-the-data/.

Enchautegui, Maria E. 2015. ‘Immigrant and Native Workers Compete for Different Low-Skilled Jobs’. Urban Institute, 13 October. https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/immigrant-and-native-workers-compete-different-low-skilled-jobs.

Foster, George. 1965. ‘Peasant Society and the Image of the Limited Good’. American Anthropologist 67 (2): 293–315.

Hoban, Brennan. 2017. ‘Do Immigrants “Steal” Jobs from American Workers?’ Brookings Now, 24 August. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brookings-now/2017/08/24/do-immigrants-steal-jobs-from-american-workers/.

Holpuch, Amanda. 2018. ‘Guatemalan Migrant Girl, Seven, Dies in US Border Control Custody’. The Guardian, 14 December. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/dec/14/guatemalan-girl-aged-seven-dies-in-custody-on-us-mexican-border.

Hugo, Kristin. 2018. ‘Body of Seven-Year-Old Migrant Child Who Died in US Custody at Border Returned to Guatemala’. The Independent, 25 December. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/migrant-child-death-us-border-guatemala-jakelin-caal-maquin-a8699086.html.

Isacson, Adam, Maureen Meyer, and Adeline Hite. ‘“Come Back Later”: Challenges for Asylum Seekers Waiting at Ports of Entry’. WOLA, Advocacy of Human Rights in the Americas, 2 August. https://www.wola.org/analysis/come-back-later-challenges-asylum-seekers-waiting-ports-entry/.

Jordan, Miriam. 2018. ‘“A Breaking Point”: Second Child’s Death Prompts New Procedures for Border Agency’. New York Times, 26 December. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/26/us/felipe-alonzo-gomez-customs-border-patrol.html.

Kiely, Eugene, Lori Robertson, Robert Farley, Brooks Jackson, and D’Angelo Gore. 2019. ‘Fact Checking Trump’s Immigration Address’. FactCheck.Org: A Project of the Annenberg Public Policy Center, 9 January. https://www.factcheck.org/2019/01/factchecking-trumps-immigration-address/.

Kohn, Sally. 2016. ‘Nothing Donald Trump Says on Immigration Holds Up’. Time Magazine, 29 June. http://time.com/4386240/donald-trump-immigration-arguments/.

Kreft, Sönke, David Eckstein, and Inga Melchior. 2016. Global Climate Risk Index 2017. Berlin: German Watch. https://germanwatch.org/sites/germanwatch.org/files/publication/16411.pdf.

Mark, Michelle. 2018. ‘The 8-Year-Old Migrant Boy Who Died on Christmas Eve Was Held in US Custody for Nearly a Week – against Border Patrol's Own Rules’. Business Insider, 26 December. https://www.businessinsider.com/felipe-gomez-alonzo-border-patrol-custody-death-2018-12.

Martin, Maria. 2019. ‘Killings of Guatemala's Indigenous Activists Raise Specter of Human Rights Crisis’. National Public Radio, 22 January. https://www.npr.org/2019/01/22/685505116/killings-of-guatemalas-indigenous-activists-raise-specter-of-human-rights-crisis.

Miller, Talea. 2011. ‘Malnutrition Plagues Guatemala’s Children’. PBS News Hour, 16 February. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/latin_america-jan-june11-nutrition_02-16.

Oglesby, Elizabeth. 2019. ‘How Central American Migrants Helped Revive the US Labor Movement’. The Conversation, 18 January. https://theconversation.com/how-central-american-migrants-helped-revive-the-us-labor-movement-109398.

Renton, Alex. 2014. ‘Latin America: How Climate Change Will Wipe Out Coffee Crops – and Farmers’. The Guardian, 24 March. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/mar/30/latin-america-climate-change-coffee-crops-rust-fungus-threat-hemileaia-vastatrix.

Schlein, Lisa. 2018. ‘UNHCR: People Seeking Asylum Have Legal Right to Enter US’. Voice of America, 21 October. https://www.voanews.com/a/people-seeking-asylum-have-legal-right-to-enter-us-territory/4622526.html.

Shire, Warsan. 2011. Teaching My Mother How to Give Birth. London: Flipped Eye Publishing, Mouthmark series.

USAID. 2019. ‘Where We Work: Guatemala’. Washington, DC: Maternal and Child Survival Program, USAID. https://www.mcsprogram.org/where-we-work/guatemala/.

US Department of Homeland Security. 2018. ‘CBP Shares Additional Information about Recent Passing of Guatemalan Child’. 25 December. https://www.dhs.gov/news/2018/12/25/cbp-shares-additional-information-about-recent-passing-guatemalan-child.

Valverde, Miriam. 2019. ‘Were Migrant Children Who Died Very Sick before Taken into U.S. Custody, as Trump Claimed?’ Politifact, 3 January. https://www.politifact.com/truth-o-meter/article/2019/jan/03/were-migrant-children-very-sick-border-patrol-took/.

Velásquez Nimatuj, Irma A. 2018. ‘An Open Letter to President Donald J. Trump and the Government of the United States of America’. Skylight, 22 October. https://skylight.is/2018/10/an-open-letter-to-president-donald-j-trump-and-the-government-of-the-united-states-of-america/. Translated from ‘Carta al presidente Donald Trump y al goberierno de Estados Unidos de América’. El Periodico, 19 October. https://elperiodico.com.gt/opinion/2018/10/19/carta-al-presidente-donald-trump-y-al-gobierno-de-estados-unidos-de-america/.

Ward, Joe, and Anjali Singhvi. 2019. ‘Trump Claims There Is a Crisis at the Border. What’s the Reality?’ New York Times, 11 January. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/01/11/us/politics/trump-border-crisis-reality.html.

World Bank. 2017. ‘Mortality Rate, under-5 (per 1,000 Live Births). 1960–2017’. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.DYN.MORT.

Yates-Doerr, Emily. 2018. ‘Why Are So Many Guatemalans Migrating to the U.S.?’ Sapiens, 25 October. https://www.sapiens.org/culture/guatemala-migrants-united-states/.