Studying the contemporary clinic necessitates rethinking what it means to both enter and access ‘the field’. In these Field Notes, I reflect on the beginnings of fieldwork and the processes of crafting research protocols which can stand up to formal ethics reviews. Rather than treating the process as a barrier to ‘real’ ethnographic research, I suggest that the mundane institutional realities of inserting oneself into a bureaucratic atmosphere form a particular—but no less valid—kind of ethnographic experience. I call this experience ‘cubicle ethnography’, after how the structures of the office—keys, badges, desktop computers—reflected negotiations of access and my own legitimacy as a visiting ethnographer.

Cubical ethnography

Another kind of fieldwork

—

Abstract

I am walking through empty rows of cubicles on my way to a stairwell, in pursuit of a meeting that may or may not be happening, at which I may or may not be welcome. My plastic ID badge taps against the single key on my lanyard, which then clanks against my belt. The gentle tap-clank, tap-clank, tap-clank contrasts with the silence on the floor, heightening my sense of myself. I feel increasingly anxious. Like the sound, I consider myself an interruption. And yet I am still here, reading the sign above the coffee-maker, which reminds us, gently, to ‘wash me when you’re done!’ I notice how the same bottle of water remains cool, awaiting its purpose for months in a dorm-sized mini-fridge. I am still showing up, still attempting to actualise something like the fieldwork I imagined, while struggling to live through my experience not as a prelude to the main event, but as the thing itself. Cubicle ethnography.

While for many anthropologists (exponentially more in the time of COVID-19), ‘the field’ is already a non-place, I found the roomful of more-often-empty-than-not cubicles a particularly ironic non-place. Despite my fantasies of intimacy, themselves stemming from stagnant geography, my entry into the field felt more like an office sitcom than an anthropological adventure. In my slightly broken desk chair surrounded by grey felted walls, occasionally in the company of others in liminal positions—interns—I was incessantly plagued by the question of access, which also became a question of entitlement. Was this ‘the field’? What was it that I wanted ‘in’ to? And what justifies interrupting something as critical as medical care for the sake of a dissertation?

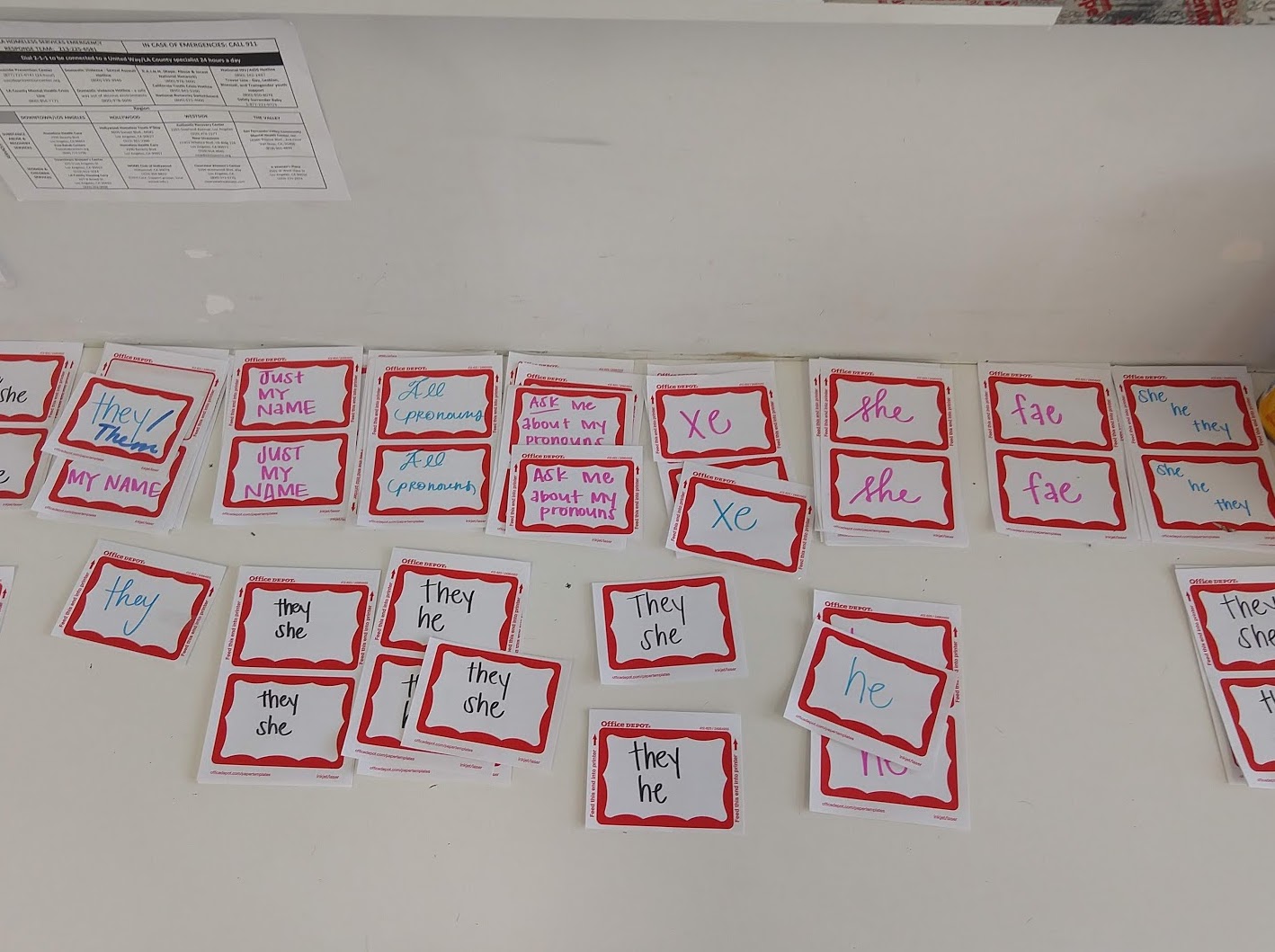

My research asks how gender is enacted within the context of clinical medical care by tracking the provision of gender-affirming medicine to young people in the United States—young people like Riley, a five-year-old who had entered the room with one burning question for the doctor: ‘How do you make a vagina?’, and Quentin, whose rainbow chucks dangled off the edge of the exam table as he talked about the prospect of going off to theatre camp with his newly prescribed testosterone gel packed alongside his toothbrush and allergy medication. These young people and their parents were generous enough to permit me to lurk in the corner of the exam room while they spoke with their providers, only asking me to step out when it was time for a physical exam and when parents were also required to leave, allowing for some deepened privacy between the doctor in question and her patient. From the beginning, it felt miraculous to even find a clinic which was, in theory, open to an ethnographic observer. Of course, this was only the beginning of a much longer process of finding my way in and reconciling my idea of what access was with the experience of obtaining it.

As other ethnographers of hierarchical and deeply bureaucratic institutions will recognise, the distance between the fourth floor and the fifth is often far greater than a single flight of stairs would suggest. As I sat in my cubicle, I imagined what was happening underneath my feet, what conversations were taking place in open doorways, which doctors were dashing to find copies of flyers or ask their colleagues about odd lab results or strategies for managing a particularly challenging parent. I knew that for me to be present for even some of those conversations, I needed to construct a set of protocols that would hold up to the far more demanding stipulations of hospital IRB administrators, one of whom characterised my project (not unkindly) as a ‘total surveillance’ of the clinic’s goings-on. My expectation—that I should be able to simply ‘be’ around the clinic in as natural a way as possible so as to better notice the ways that gender and gender care are described and practised—may not strike anthropologists as strange in the least, but it came across as quite strange to those charged with protecting the integrity of the clinic. For them, it was impossible to consider assenting to the project’s progression without first receiving a far more detailed account of my own intentions and the safeguards I had in place. As such, I had to deeply consider how I would be able to communicate the breadth and depth of my observations to those who worked and sought treatment at the clinic.

During the first weeks of my residence among the fifth-floor cubicles, I considered that the work I was doing on the fifth floor was not merely preparation for ‘real’ work (i.e., fourth-floor work) but was an ethnographic experience in and of itself. This thought process allowed me to explore the undergirding assumptions of the anthropological entitlement to access; the way, for instance, we are trained to imagine and justify our belonging in spaces to which, for many of us, we do not belong. In the beginning, I spent my days alternating between anxiously sweating through group meetings, where I inevitably fumbled over my own introduction (hello, I am an anthropologist, a graduate student . . . an ethnographer? Hello, I am here to do my dissertation research? Hello, I am here working with the clinic? The trans youth program? Hello, I am . . . from Chicago?), and sitting in a bank of cubicles working on an ever more detailed set of research protocols. These protocols outlined my role as someone who would be able to encounter, if not use, legally protected ‘Personal Health Information’.

Envisioning how to avoid capturing information like legal names, birthdates, and diagnoses was a major component of the months I spent dreaming of gaining access to what I imagined was the clinic itself. But my protocols didn’t only need to account for how I would distinguish my own data from protected heath information; they also needed to communicate how I planned to discipline myself as an observer. I needed to describe and justify how I would provide ongoing opportunities for employees, especially those who would become acclimated to me and my ever-present black notebook, to say ‘no’—to tell me to leave a meeting, to strike a conversation out of my notes, to remove data which I may have encountered but did not actually have the right to access, even to simply decline the ‘opportunity to participate in a research project’, which did not, after all, offer any benefits.

Much of this kind of work remains invisible in anthropological scholarship, though I have no doubt that it makes up much of the time researchers spend in the field. When I looked for guidance and models, most of the anthropological writing on paperwork, consent processes, and other practices of ‘the cubicle’ (see in particular Lederman 2006 and that series of papers in American Ethnologist) seemed to circulate complaints about how modern ethics review is poorly suited to judging the riskiness of ethnographic methods. At the same time, considering the grounding of anthropology itself—the ways in which the ethics of colonialism and white supremacy fuel and justify the exposure of communities to study, where access is treated as entitlement rather than something to be negotiated—it seemed to me that the requests for clear and pragmatic plans were also a way of learning what it meant to be granted access to contemporary medical infrastructures of care. As my primary contact wrote to me immediately after I had relocated to a new city for the project, she was ‘quite protective’ of her team and her patients. Why should I be trusted?

She wanted to know my intentions, as most do. The ‘why’ of the project and the ‘why’ of this place, these people. But even after supplying a reasonably satisfactory answer, I remained deeply uncertain of my role in relation to the clinic—and this before I had even embarked upon the work that I would soon begin to understand as cubicle ethnography.

For those of us embedded in bureaucracy (which, to some extent, all institutionally legitimised academics and proto-academics are) as a part of our ethnographic experience, what I call ‘cubicle ethnography’ refers to a particular kind of institutional experience. It seemed to me that, as I obtained trust and access through the distanced mechanisms of paperwork, key cards, and Outlook calendars, my experience felt different than I had expected institutional ethnography to feel. Rather than building relationships through informal networks of friendships or by simply being there, I celebrated other wins, like landing an internal email address or realising I could pick up the phone on my desk to call tech support when my desktop stopped turning on. More importantly, rather than taking those as perfunctory actions that simply provided the infrastructure to do the work my protocols described—the work that let me meet Riley, Quentin, and more than 50 other young patients—I started to see such work as valuable in its own right.

Accepting the construction of research protocols as an ethnographic process in itself forced a much more rigorous process of accounting for myself. It allowed me to see the personal and professional boundaries emerging around me not as obstacles to be worked through but as legitimate restrictions on what I was entitled to access. In hindsight, it seems clear that all of the work I did to pass through the clinic review was also necessary to understand the infrastructure of the clinic itself. It was quintessentially ethnographic in that what I learned from being there wasn’t anything I could have known to ask.

A month or two before I was scheduled to leave the clinic and return to Chicago, my academic home, I had scheduled a meeting with a medical fellow (Anna) during which I planned to conduct a brief interview about her experience working at the gender clinic. One of the many pleasures of Southern California is that it’s almost always possible to meet outside, and so we had decided to have our conversation on the patio attached to the staff breakroom. The room was locked, as usual, and I had arrived early, also as usual. Anna’s office was along the same hallway, so I poked my head in through the doorframe and said, ‘Hi!’

She sat at her desk, typing, with her blue striped ID badge marking her as a physician, just as my orange stripe marked me as a trainee, the only category on the form I had filled out that seemed broad enough to encompass my nearly illegible status as ‘volunteer ethnographic researcher from another institution and definitely not a doctor’.

Anna asked if she could have a few more minutes and I replied, ‘Of course, I can just wait.’

She looked a little confused, and said, ‘We can just meet on the patio.’

‘Oh, I don’t think I can unlock that door. I just have a key to the fifth floor, where the social work interns have their cubicles.’

Anna raised her eyebrows. ‘The universal key? I’m pretty sure it works on that door too.’

Flustered, but with dawning understanding of just how much more sense that would make, I laughed at myself and promised to give it a try.

The key worked perfectly. Anna and I chuckled about it later, and she told me how the same key would also open her office door, and probably most of those on that floor too . . .

I had never bothered to try the key in the break room door, or in any other door besides the one I was specifically told that it worked in, despite my many days spent sitting in my solitary cubicle wishing for more opportunities to be ‘somewhere’ ‘something’ was happening. Now, I can only reflect on the myriad ways that access, and trust, is materialised. I think it means something that my key opened doors I didn’t try, and I think it means something that I had to learn to embrace the institutional performance of acceptable research as also a performance of my willingness to be a part of the process; to open myself up to the organisation I was asking to be open to me.

Cubicle ethnography is not romantic. There are some early mornings, fewer late nights. I never managed to snag an invitation to happy hour among the core staff, whose offices a floor away meant that we saw each other at meetings and sometimes in the elevator. The ethnographic experiences of the cubicle, of the elevator, and the silent hallway, like the nods of the security guard doing rounds, have less to say about what it means to study the clinical care of gender than about what it means to undertake contemporary anthropology in a hyper-regulated and distanced world (when this regulation is in part to mediate the harms that research, and researchers, have done and continue to do). But the note that I would like to end on is this.

In spring, I leave for a week. It’s graduation season. The social work interns, whose two-days-a-week schedules sometimes overlap with mine, are moving from unpaid labour into mostly under-compensated positions across the city. When I return, all of their cubes are even emptier than before; the pinned photos or books that used to offer a bit of personality have gone missing. On my desk, though, is a small wallet photo of a young person wearing a graduation cap and gown. Thanks, they say to me in a little note. Stay in touch. Their picture goes into a (small) stack of personal cell phone numbers and information about people’s kids, divorces, pets. The little body of evidence, for myself, that the cubicle is a place too.

Acknowledgements

This research has been supported by the Wenner-Gren Foundation, the University of Chicago Center for the Study of Gender and Sexuality, and the Gianinno Graduate Research Award. This work would not have been possible if not for the willingness of the clinic staff, interns, and patients; I am immensely grateful for their patience and generosity.

About the author

Paula Martin is a PhD candidate in the Department of Comparative Human Development at the University of Chicago and a graduate of the School of Social Service Administration. Her work sits at the intersections of medical anthropology, gender studies, and feminist science and technology studies. In her dissertation, she tracks how gender-affirming medicine is understood and utilised by providers, youth, and their families in the contemporary United States. Through clinical participant observation, in-depth interviews with experts and youth, as well as analysis of current trends in the clinical research on gender care, her dissertation explores interrelated logics of gender, temporality, and knowledge.

References

Lederman, Rena. 2006. ‘Introduction: Anxious Borders between Work and Life in a Time of Bureaucratic Ethics Regulation’. American Ethnologist 33 (4): 477–81. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.2006.33.4.477.