As 'psychosocial interventions' continue to gain traction in the field of global mental health, a growing critical literature problematises their vague definition and attendant susceptibility to appropriation. In this article, I recast this ill-defined quality as interpretive flexibility and explore its role in processes of translation occurring at the frontlines of care in rural Nepal. Drawing from 14 months of ethnographic fieldwork among community-based psychosocial counsellors, I consider how the broad and flexible notion of the 'psychosocial problem' operates as a 'boundary object' in transnational mental health initiatives—that is, how it facilitates the collaboration of service users, clinicians, donors, and policymakers in shared therapeutic projects without necessarily producing agreement among these parties regarding the nature of the suffering they address. I suggest that psychosocial interventions may be gaining popularity not despite but precisely because of the lack of a unitary vision of the problems psychosocial care sets out to alleviate. In closing, I reflect on what distinguishes 'psychosocialisation' from medicalisation and highlight the limitations of the latter as a critical paradigm for the anthropology of global mental health.

Psychosocialization in Nepal

Notes on Translation from the Frontlines of Global Mental Health

—

Abstract

Introduction

As I waited at a crowded bus stop with Kalpana—Ashrang’s first and only psychosocial counsellor—a middle-aged woman nearby struck up a conversation. [1] The dialogue quickly slipped into a familiar groove. The woman enquired, politely, what I was doing in this out-of-the-way corner of the Himalayan foothills. By way of explanation, Kalpana began talking about the six-month psychosocial counselling training course in Kathmandu where we had first met. Her job now, she said, was to help people who were continuously worrying, who couldn’t sleep, and who were very afraid. ‘People who have a lot of heart-mind problems,’ she summarised. She continued that the counselling she did—here using the lay term for giving counsel, paraamarsa, rather than the technical term for psychosocial counselling, manobimarsa—involved having a conversation with someone to help them find a solution to their particular problem. ‘Before the earthquake there was not much of this support,’ she explained, ‘but now there is more.’

The woman listened attentively, registering understanding in her facial expression. ‘Oh, you mean people who are very afraid all the time?’ she asked, and then added, ‘there are some people like this in my village.’ She disappeared into the crowd, emerging a few minutes later with a neighbour whose daughter, she told us, had ‘this type of problem’. For months, the girl had been complaining of excessive fear and refused to leave the house, even to attend school. After some further discussion, the young mother asked how she could meet Kalpana again and the two women exchanged numbers. Kalpana reassured her that she would visit, adding, ‘Don’t be afraid. We are here. And if we can’t solve the problem, I will send someone else who can help.’

Living with a newly trained counsellor as she established the first psychosocial services in her region, I witnessed exchanges like this one on a regular basis. It quickly became clear that almost no one living in Sindhupalchok district had heard the Nepali word ‘psychosocial’ [manosaamaajik] before. More surprisingly, Kalpana also used the term sparingly, even though it was precisely the identification of a psychosocial problem that served as a gateway to counselling and other mental health services.

Intrigued, I began systematically asking counsellors across the district how they explained their work to people in the communities they served. I was particularly interested in how they navigated initial meetings with potential clients and their families, during which the status of a given problem as psychosocial (or not) was negotiated. Given a growing critical literature on psychosocial interventions, I was curious about the implications of recasting rural Nepalis’ suffering in psychosocial terms: did this framing efface or supplant other locally salient framings of distress? Did it medicalise normal responses to adversity and structural violence, undermining individual agency and throwing open the door for new forms of therapeutic governance?

In this paper, I argue that we cannot begin to answer these important questions without careful attention to the communicative practices of frontline clinicians, among whom psychosocial counsellors occupy a prominent place in Nepal. These frontline practitioners sit at the nexus of not only different vocabularies, ethnopsychologies, and ontologies of suffering, but also different regimes of value, all highly consequential in terms of how care is pursued and provided. The ways in which counsellors represent the object of their care to potential clients have tremendous implications not only for the course(s) of therapy individuals choose to pursue, but also for how notions of mental disorder and psychosocial disability take on meaning and legitimacy in relation to other locally salient readings of affliction.

In what follows, I begin by tracing the ascent of psychosocial models of care in Nepal and more widely in the field of global mental health (GMH). I then draw on conversations with psychosocial counsellors working in one predominantly rural hill district of Nepal to explore the microdynamics of what I here term ‘psychosocialisation’: the process through which varied human problems come to be construed as appropriate objects of psychosocial care (cf. Abramowitz 2014). Zooming in on the interactions of frontline counsellors and potential clients, I examine how the vague and flexible category of the ‘psychosocial problem’ is deployed in everyday practice with particular attention to its role in processes of translation.

My use of ‘translation’ here encompasses, but is not limited to, the linguistic and cultural adaptations that GMH practitioners are themselves increasingly concerned with. Drawing inspiration from science and technology studies (STS) and in particular the work of Susan Leigh Star, I understand translation as a process that strives not merely to convey meaning to people in different sociolinguistic worlds, but also to enlist their support and cooperation (Callon 1986; Callon and Law 1982; Star and Griesemer 1989; Star 2010). Star’s key intervention was her insistence that such cooperation can be achieved even in the absence of consensus about the problem at hand; for example, scientific experts, donors, bureaucrats, and amateur enthusiasts can work together to realise projects without necessarily agreeing about what is at stake (Star and Griesemer 1989; Star 2010). [2] This collaboration is facilitated, she argues, by ‘boundary objects’:

objects which are both plastic enough to adapt to local needs and the constraints of the several parties employing them, yet robust enough to maintain a common identity across sites. They are weakly structured in common use, and become strongly structured in individual-site use […] They have different meanings in different social worlds but their structure is common enough to more than one world to make them recognizable, a means of translation. (Star and Griesemer 1989, 393).

While somewhat dated and not without its shortcomings, [3] I suggest this original formulation of the boundary object helpfully singles out important qualities of the ‘psychosocial problem’ in GMH today—namely, the ways it facilitates collaboration in complex transnational therapeutic endeavours without requiring different stakeholders to first reach consensus about the nature of affliction. I then discuss the implications of this analysis for the anthropology of GMH, arguing that available critical lenses in medical anthropology fall short of capturing the distinct discursive politics at work in contemporary processes of psychosocialisation. I close by sketching some lines of inquiry that might allow us to gain greater critical traction in this young and rapidly shifting field of intervention.

‘Psychosocial interventions’ in global mental health

Leading guidelines define ‘psychosocial support’ as closely related to ‘mental healthcare’, adopting a different approach to achieve overlapping aims (Inter-Agency Standing Committee 2007). While mental health services focus on curing disorders (frequently with the help of medication), psychosocial care is generally geared towards alleviating distress or improving functioning and wellbeing using non-biological therapeutic interventions (Psychosocial Working Group 2003, 1). In recent years, psychosocial approaches have enjoyed growing popularity within global mental health (GMH), a young and interdisciplinary field concerned with scaling up mental health services in low- and middle-income countries (White et al. 2017).

Whereas early GMH initiatives foregrounded evidence-based psychiatric treatments, advocates have progressively rebranded the movement as one that transcends the psychiatric paradigm (Bemme and Kirmayer 2020). Bemme’s (2018) nuanced genealogical work describes how GMH actors began to downplay rigid psychiatric nosologies in favour of a broad and malleable ‘umbrella language’ for mental health, one which is well-aligned with psychosocial approaches. Leading figures in GMH now claim that the majority of problems captured in the global burden of mental disorders would be better labelled mental ‘distress’ (Patel et al. 2014a, 18) and have called for the expansion of the field’s purview from the treatment of mental illness to the promotion of mental health and wellbeing (Patel et al. 2018). The guiding problematisation of the global ‘treatment gap’ has given way to the more inclusive ‘care gap’, which explicitly eschews the ‘medical connotation’ that was seen as excluding ‘a range of effective psychosocial interventions available today’ (Pathare, Brazinova, and Levav 2018, 1; Patel et al. 2018). Indeed, the latest The Lancet commission on GMH suggests psychosocial interventions delivered by non-specialist workers should be the ‘foundation of the mental health-care system’ going forward (Patel et al. 2018, 9).

Beyond reflecting ideological developments, the embrace of psychosocial interventions in GMH is also a practical response to the challenges of implementation in diverse low-resource settings. Psychosocial interventions are more feasible to deliver through ‘task shifting’, or the delegation of clinical tasks to non-specialist workers who often lack the training to distinguish between different disorders. They are also seen as more ‘acceptable’ to people holding divergent ideas about mental illness, enabling practitioners to overcome ‘demand-side barriers’ to care (Patel 2014; Kohrt and Griffith 2015).

Thus far, social science critiques of GMH have drawn heavily on well-worn Foucauldian tropes, often adopting ‘the usual frame of the battle between medicalization and its discontents, experts and patients, and the colonizing reach of disciplines and the insurgencies beating them back’ (Béhague and MacLeish 2020, 10; see also Ecks 2020; Cooper 2016). In this vision, GMH catalyses the mass medicalisation of mental suffering across the Global South, undermining local cultural knowledge and deflecting attention away from social and structural determinants; the field is often described as an extension of or complicit with various wider efforts at social and economic control (e.g., Clark 2014; Das and Rao 2012; Mills 2014; Mills and Fernando 2016; Kottai and Ranganathan 2020; Watters 2010; Fernando 2011; Summerfield 2012).

Within this critical literature, psychosocial interventions have been described as poorly defined, amplifying the potential for appropriation and unintended consequences (Kohrt and Song 2018; Watters 2010; Pupavac 2002). For example, Abramowitz’s (2014, 25) compelling ethnographic case study in Liberia describes psychosocial interventions as a vector for ‘humanitarian social engineering’. The lack of a clear definition of psychosocial care, she argues, gave license to international organisations to remould Liberian subjectivities as they saw fit. Liberian counsellors working for these organisations were in turn empowered to act as ‘moral missionaries’, imposing their own interpretations of normative humanitarian values—at times quite forcefully—on clients and community members (Abramowitz 2014, 113).

Abramowitz’s rich ethnographic account stands as a stark warning of how psychosocial interventions can be exploited to diverse social and political ends. At the same time, it reveals the extent to which these ends are shaped by frontline clinicians, whose positioning and labour ‘complicate our all-too-routine differentiation of medical healing systems into “the global” and “the local”’ (Abramowitz 2010, 326). The next step forwards, Abramowitz (ibid.) suggests, is to bring ethnographic scrutiny to bear upon the subjective experience of these actors at the frontlines of care. What follows is an offering in this direction. After introducing my research context and methods, I provide a close reading of Nepali counsellors’ accounts of the translational work they engage in. My analysis asks: how might these accounts challenge, exceed, or refine the critical frames through which we approach the GMH project?

Psychosocial care in Nepal

Nepal is widely described in the global mental health (GMH) literature as suffering from a dire shortage of mental healthcare resources, with only a single public mental hospital and an estimated 110 psychiatrists and 15 clinical psychologists serving a population of 29 million (Sherchan et al. 2017). The first psychosocial counselling programmes were introduced during a violent Maoist insurgency that racked the country from 1996–2006 (Seale-Feldman 2020a). Exemplifying ‘task shifting’, these programmes trained two new cadres of frontline practitioners: psychosocial counsellors (four to six months of training) and community psychosocial workers (one to two weeks of training) (Kohrt and Harper 2008).

The practitioners who developed these early psychosocial programmes were influenced by medical anthropology, including research on ethnopsychology and idioms of distress (Sharma and van Ommeren 1998; Tol et al. 2005; Jordans et al. 2003). Physician-anthropologists Kohrt and Harper (2008) identify two distinct Nepali concepts of ‘mind’ that influenced service design: the ‘brain-mind’ [dimaag] located in the head, associated with rational thought and behaviour, and the ‘heart-mind’ [man] in the chest, the site of transient everyday thought and emotion. Terms associated with disorder of the brain-mind, such as ‘mental illness’ [maanaasik rog], carry stigmatising connotations of moral failure, chronicity, and severity that may deter people from engaging with services (Kohrt and Hruschka 2010; Kohrt and Harper 2008). Psychosocial programmes in Nepal have attempted to distance themselves from these connotations by claiming to address suffering in the ‘heart-mind’ (Kohrt and Harper 2008). Accordingly, the Nepali neologism for ‘psychosocial’ combines the terms man [heart-mind] and samaaj [society], and the word adopted for ‘psychosocial counsellors’, manobimarsakarta, can be translated as ‘person who advises on matters of the heart-mind’ (ibid.).

In the post-conflict period, this ‘culturally adapted’ model of psychosocial care was progressively formalised and expanded in a piecemeal fashion into different parts of the country. By the early 2010s, Nepal had become an important node in the GMH assemblage, and its flagship research programme incorporated psychosocial counsellors as one element of an essential mental healthcare package (Jordans, Luitel, Kohrt, et al. 2019; Jordans, Luitel, Garman, et al. 2019). The devastating earthquake of 2015 rallied ample funding and political support for mental health, and advocates worked to channel the sudden influx of resources towards the goal of sustainably scaling up services across the country, or ‘building back better’ (Seale-Feldman and Upadhaya 2015; Seale-Feldman 2020b; Chase et al. 2018).

My doctoral research charted this moment of optimism through 14 months of ethnographic fieldwork (2016–2017). [4] Following preliminary research among programme planners and clinicians in Kathmandu, I relocated to the rural hill community I here call ‘Ashrang’, in the heavily earthquake-affected Sindhupalchok district. In the two years following the disaster, mental health and psychosocial services had become available to Ashrang’s 6,000–8,000 residents [5] for the first time. A government-financed psychosocial support centre was established and staffed by a psychosocial counsellor (Kalpana) and two community psychosocial workers. [6] The region’s female community health volunteers (a lynchpin of the government’s health delivery system in rural areas) received training in the identification of and referral for mental health problems. A Kathmandu-based psychiatrist began visiting a pharmacy in a nearby town once a month to perform consultations, and three primary care doctors working in another nearby town received training modelled on the World Health Organization’s (WHO) mhGAP Intervention Guide and a supply of psychotropic drugs. These services and goods were free for patients with the exception of certain psychotropic drugs not on the government’s free drugs list. Referral between these different services was possible, but was limited in practice by poor coordination.

During my time in Ashrang, I lived with Kalpana and her family and participated as fully as possible in everyday community life. I conducted immersive participant observation among and interviews with frontline clinicians, former clients, and caregivers associated with the psychosocial support centre Kalpana directed. [7] I also visited and interviewed psychosocial counsellors in other parts of the district and participated in mental health and psychosocial training courses across the country. During my first months in Ashrang, Kalpana sometimes moonlighted as my research assistant and accompanied me to interviews. [8]

My ethnographic access was exceptional in two ways that are worth noting from the outset. First, the clinicians I interacted with had been trained by some of the most senior and experienced counsellors in the country at an organisation that prioritises cultural adaptation, community-based care, and anthropological insights. [9] Second, my focus was a sustainably government-financed psychosocial support programme that trained laypeople to provide counselling in their own communities. In contrast, at the national level psychosocial counselling is more often provided through short-term NGO projects and mobile teams (Seale-Feldman 2020a), while psychiatric treatments have achieved much wider coverage within the public health system to date (Chase et al. 2018). This latter point is significant because, in the many instances when clients consult biomedical providers during the course of counselling, they might find their problem suddenly refashioned as a ‘mental illness’; and, as a consequence, the complex work of psychosocialisation is swiftly undone.

As such, my account should not be read as comprehensive portrait of GMH practice in Nepal, and nor is the carefully crafted model of counselling that exists in Nepal representative of the gamut of psychosocial interventions in use internationally. Instead, what my vantage point afforded was a glimpse of one of the field’s most contextually sensitive and reflexive frontiers and the aspirational politics it embodies. In practitioner-speak, you might call this an ethnography of ‘best practice’.

In order to develop a more vivid picture of this frontier, I turn now to two ethnographic vignettes that situate processes of psychosocialisation in the everyday life and work of frontline counsellors. Each sheds some light on how the broad and flexible category of ‘psychosocial problems’ might enable cooperation among people who hold differing views of the suffering being addressed through counselling (mental health researchers, counsellors, and clients). I then draw from interviews with counsellors across the district to examine the specific challenges they faced when attempting to secure cooperation from potential clients as well as some common translational strategies they used to accomplish this. In all direct quotes that follow, words that were spoken in English rather than Nepali are italicised.

Two psychosocial problems

Radha

In spring 2017, the Kathmandu-based professionals planning psychosocial programmes and frontline counsellors like Kalpana worked under starkly different conditions. While the capital city showed few visible traces of the earthquake that had rocked it two years earlier, the vast majority of residents in Ashrang still lived in provisional shelters of corrugated metal—‘huts [chhaapro], not homes [ghar]’, people often corrected me. When two counsellors from another part of the district visited Ashrang one morning, Kalpana and her mother-in-law seated them on the only portion of their old house still standing: a large, uncovered concrete slab jutting out from the hillside supported by the unliveable remains of two rooms below. This open concrete surface, adjacent to the cramped hut where they now slept, had become the heart of everyday family life; it was here that food was cooked over open fires, meals were eaten cross-legged on straw mats, harvests were dried in the sun, and a steady stream of visitors were entertained.

The counsellors, Prakash and Krishna, were visiting on their day off simply to pass the time. Prakash had made a professional visit once before and was on friendly terms with my host family. As we chatted casually under the beating sun, a gaunt and balding old man approached. My body tensed up as I recognised Chakrit, a severe alcoholic known for his violent impulses. This morning he was already visibly intoxicated. He sat down in an empty plastic chair and asked for a piece of the freshly picked cucumber my host mother was cutting for our guests. Kalpana handed him a slice.

After placing the cucumber in his mouth, Chakrit leaned sharply to one side, upending his chair and rolling onto the concrete below. He began to sob loudly, slapping himself all over his body and then slapping the hard ground. As we looked on, he spat out the half-chewed cucumber and then picked the mush up and anointed the centre of his forehead with it in mock ceremony.

While I kept my eyes fixed on Chakrit in fear of what he would do next, Krishna began to talk knowledgeably about the withdrawal response of people addicted to alcohol. This piqued my curiosity; if the counsellors had relevant training, why hadn’t Chakrit been identified as a candidate for their services, as someone with a ‘psychosocial problem’? They later explained to me that if an addict sought help—something Chakrit had never done—they could provide counselling and referrals. But a case as severe as Chakrit’s would require medication and the support of a rehabilitation centre, and the nearest was three hours away. Under these conditions, trying to enlist Chakrit in psychosocial services seemed futile. In contrast, Chakrit’s wife Radha was one of first counselling clients Kalpana had enrolled.

As Chakrit continued to sob loudly, Kalpana’s mother-in-law told our guests about Radha’s misfortunes. She explained that Chakrit had been savagely beating his wife for decades. With both humour and vindictiveness in her voice, she recounted a night she had spent at the home of the couple’s neighbour years earlier. When the noise from Chakrit’s beatings kept them awake, she and her hosts marched next door and threatened to tie up his hands and feet.

In later years, relatives and even the local women’s cooperative intervened on Radha’s behalf, but the solutions were always temporary. Chakrit always resumed drinking and beating his wife, and Radha gradually became a meek and dishevelled old woman. When a mental health researcher from Kathmandu visited to evaluate the impact of the new psychosocial support centre, he told me that Radha suffered from severe post-traumatic stress disorder and suicidal ideation. But Kalpana, Radha’s only clinical contact, had not been trained to identify mental disorders. When her mother-in-law finished speaking, Kalpana turned to her colleagues and translated Radha’s predicament into the technical language they shared: ‘She has a psychosocial problem.’ Prakash and Krishna shook their heads, comprehending.

Although Kalpana and the Kathmandu-based mental health researcher had different understandings of what ailed Radha—locating her problem in her heart-mind and her brain, respectively—the identification of a ‘psychosocial problem’ enabled a shared recognition that she required care and that counselling was an appropriate response. This shared recognition was crucial for cooperation between frontline counsellors and the more highly trained mental health experts funding, supervising, and evaluating their work. As Bemme (2018) has argued persuasively, the embrace of broad and flexible therapeutic objects—such as the ‘psychosocial problem’—facilitates these kinds of multi-disciplinary collaborations in GMH. Yet the success of GMH interventions requires the cooperation of another equally important stakeholder, one that could be surprisingly difficult to engage in the rural Nepali context: the client.

Tara

After weeks of gentle nagging, I convinced Kalpana to clear an afternoon in her busy schedule to accompany me during my interview with Tara. Tara had been disabled by paralysis of the feet and housebound for over two years. She lived with her deaf, elderly mother, who worked as a labourer in neighbours’ fields during the day. As I grew to know Tara over sporadic cups of tea, I learned that the onset of her paralysis coincided with a string of difficult events in her life. Tara’s husband had been convicted of a heinous crime and imprisoned. Refusing to remain in her husband’s house, Tara moved with her daughter to Kathmandu, but she soon lost custody of the girl to her in-laws.

The first night Tara slept alone in her rented room in the capital, she awoke to a searing pain in her feet and discovered she could no longer walk. She suspected that her affliction was the result of witchcraft and sought the help of a series of shamans and mediums. By the time we met two years later, she expressed a mixture of doubt and hope about the costly rituals that had yielded some relief, but never a cure.

Tara sat with Kalpana and me for hours as the monsoon rain thundered against the metal roof of her sparsely furnished hut. She spoke at length about the circumstances surrounding the mysterious onset of her paralysis, recounting in excruciating detail how her daughter had been wrested away from her by conniving in-laws. As she described the state of despondency she fell into thereafter, I recognised a number of the complaints I had heard Kalpana use to describe ‘psychosocial problems’: loss of appetite, not listening to others, talking non-stop, staring off into space, and remaining fixated on one thing. Seizing on these details, Kalpana intervened in my interview: ‘Being fixated on one thing like that, had that happened to you before, or was it just at that time that this happened?’

Tara explained:

First when I started to work alone, I could only think, ‘How can I pass the time alone? How can I educate my daughter? Even though I didn’t study myself, I have to educate her in a good school, give her good food and clothes in Kathmandu. I also can’t go back to my natal village.’ Now that I had no one to look after me, they weren’t looking after me.

‘You kept thinking that in your heart-mind?’ Kalpana enquired.

‘Yeah,’ Tara responded, ‘I kept thinking that in my heart-mind. And that jerk [my husband], I kept remembering him …’

Again Kalpana interrupted with a question: ‘Anyway, because of him you had a big wound in your heart-mind?’

‘Yeah,’ Tara agreed before attempting to pick up the thread of her story again.

But Kalpana had more to say:

That wound, that anguish [piDaa] happened in your heart-mind, no? That anguish is all in the heart-mind, but in one’s own body what shows? Being fixated on one thing, not feeling like eating—our body showed that […] it is that anguish that is showing. But what people say is, ‘Oh this problem is nothing.’

It was only when sifting through my interview transcripts months after this exchange that I recognised what Kalpana had accomplished in just a few sentences. Without using any technical jargon, and drawing directly from Tara’s own account of what happened to her, Kalpana had reframed Tara’s suffering as a problem amenable to precisely the type of care she was trained to provide. This new framing was consistent with lay understandings of distress and care in rural Nepal—for example, that difficult life experiences cause emotional wounds, that such wounds might steal one’s appetite, and that sharing with others afforded some measure of relief (Chase et al. 2013). Where it departed from received wisdom about the heart-mind’s suffering was in the weight and moral valence accorded it: most people, Kalpana implied, too readily dismiss such problems as ‘nothing’, when in fact they warrant care and concern.

Crucially, drawing attention to the emotional wounds Tara had suffered did not rule out other possible labels for or explanations of her paralysis. After this initial meeting, Tara continued to surmise that she was the victim of witchcraft, even as she expressed a strong desire to share her heart-mind’s ‘tension’ in the context of counselling. Kalpana, for her part, never challenged Tara’s claims of supernatural causality and strongly encouraged her to continue the daily prayer through which she had found some relief.

In brief, Kalpana had successfully enlisted a new counselling client even while she and Tara retained quite different ideas about the nature of Tara’s affliction. Each counsellor I interviewed employed slightly different strategies and metaphors to achieve this, but several common threads ran through their accounts. In the next section, I examine these common threads more closely with a focus on the translational possibilities afforded by the flexible notion of the psychosocial problem.

Translating ‘psychosocial problems’ in rural Nepal

Categorical caution

I met Hari in his cramped office in Chautara, a small city housing Sindhupalchok district’s administrative headquarters. Hari presented as a busy and highly competent man. His desk was stacked high with papers and he received a seemingly endless barrage of phone calls, each of which he answered on the spot. Yet when I asked how he explained what ‘psychosocial’ means to potential clients during first encounters, he broke into a sheepish grin as though I were quizzing him on difficult exam material. ‘That’s very hard work!’ he exclaimed, and then laughed.

If you say exactly ‘psychosocial’, ‘mental health’, those are kind of heavy words, kind of difficult. When you say that people don’t understand, and they also get a little afraid. When you’re saying ‘psychosocial’, when you’re saying ‘psychosocial problems’, they think, ‘Uh oh, this is a big problem’.

Discussing ‘psychosocial problems’, it became clear, was a delicate task with high stakes. Frontline clinicians contended both with problems of comprehensibility and with a normative morality in which some manifestations of psychosocial problems were heavily laden with stigma and vigilantly hidden away while others were deemed unimportant and dismissed. Counsellors thus echoed Kohrt and Harper’s (2008) observation that problems labelled ‘mental’ carry connotations of moral failure that can lead to hopelessness and inaction. Yet, as Hari suggests, the unfamiliar Nepali neologism for ‘psychosocial’, smacking of technical knowledge and professionalised forms of care, was liable to provoke similar effects.

In what ways, then, did the adoption of a psychosocial approach facilitate translation? The answer, it seemed, lay not in the term ‘psychosocial’ itself, but in the leeway this flexible concept afforded counsellors to tailor and adapt their descriptions of counselling’s object to the contexts in which they worked. Unlike ‘mental illness’, which had a clear, widely recognisable equivalent in Nepali, the term for ‘psychosocial problems’ was unknown, encouraging counsellors to engage a range of creative and at times even poetic proxies.

Medical metaphors

Prakash was the oldest counsellor I met in Sindhupalchok, as well as the most experienced. He had a slow and kindly manner of speaking that always immediately put me at ease. When I asked how he interacted with potential clients during first encounters, he too suggested I had put my finger on one of the most difficult aspects of his vocation. He explained:

I don’t say ‘psychosocial’ […] The way I explain it [is] ‘in our body people can have various types of illness, no? And we also do the treatments for our illness in our body. But sometimes in our heart-mind, our heart-mind can also be sick’.

In lieu of directly translating ‘psychosocial problem’, Prakash and other frontline counsellors I interviewed relied heavily on the proxies of an illness or problem of the heart-mind, frequently drawing analogies to bodily afflictions.

At first glance, the sick heart-mind appears to be a classic example of medicalisation. Like the term ‘nerves disease’ used by some psychiatrists in Nepal as a translation for depression (Harper 2014), the ‘sick heart-mind’ seems to locate emotional distress squarely within the purview of ‘health’. Yet unlike nerves [nasaa, also translated as ‘veins’], the heart-mind [also translated as ‘mind, heart, feelings’ (Karki 2009, 313)] is not experienced phenomenologically as a body part like any other. Much like the colloquial romantic use of ‘heart’ in English, it is simultaneously bodily and abstract, experienced viscerally within the chest but distinct from the physical heart organ [muTu]. Crucially, then, counsellors’ use of medical language was transparently metaphorical rather than literal.

Nor were counsellors’ references to bodily affliction always pathologising. Sometimes discussions of heart-mind ‘problems’ evaded medical analogies altogether. Other times, as in Kalpana’s conversation with Tara, the notion of ‘sickness’ was replaced with the notion of a ‘wound’ in the heart-mind, readily recognised by laypeople as the emotional sequelae of trying life circumstances or social rupture. Although she made use of a medical metaphor, Kalpana clearly located the origins of Tara’s wound in the world of social relations rather than a biologised individual interior.

On the whole, rather than medicalising emotional distress, psychosocialisation worked more often to socialise bodily suffering as counsellors traced the roots of embodied discomfort and dysfunction to the emotional reverberations of social life. Indeed, although counselling training materials emphasise the interconnections between social, somatic, and psychological problems, in everyday practice Nepali counsellors tend to frame aetiology as a ‘one-way street’ in which social problems produce emotional and bodily effects (Sapkota et al. 2007; Kohrt and Harper 2008, 485).

New category, familiar complaints

Premila was a mother of four who had long lived in Kathmandu with her parents-in-law. It was not until the 2015 earthquake, several years after her training as a psychosocial counsellor, that she found employment in one of Nepal’s mental health NGOs. The job brought her to a town in the hills of Sindhupalchok where she lived in a rented flat during the week. On the weekends, she made the four-hour bus ride back to Kathmandu to see her family.

When I asked Premila how she explained what ‘psychosocial’ meant to potential clients, she affected the soothing voice she used in her counselling practice and offered a short, eloquent description of how the heart-mind’s wounds were reflected in the body as in a mirror. Yet after this poetic beginning, Premila quickly unpacked this relationship in far more concrete and mundane terms: ‘For example, if it has become hard for the heart-mind, the body feels tired, doesn’t feel like working, doesn’t feel like eating, doesn’t feel like sleeping, doesn’t feel like speaking.’

Over the course of my conversations with counsellors, I came to see this practice of example-listing as the most consistent element of psychosocialisation. Whichever metaphor they employed to locate a problem in the ‘heart-mind’, frontline counsellors unanimously went on to reel off a series of complaints and afflictions that anyone in rural Nepal could easily recognise and relate to. It was through such lists that abstract notions of a wound, illness, or problem in the heart-mind took on substance, that counsellors staked out the bounds of the new category of suffering they were trained to attend to. And in all the encounters I observed, it was in the course of listing that potential clients and community members first expressed understanding of what this new mode of care—that is, counselling—was trying to address.

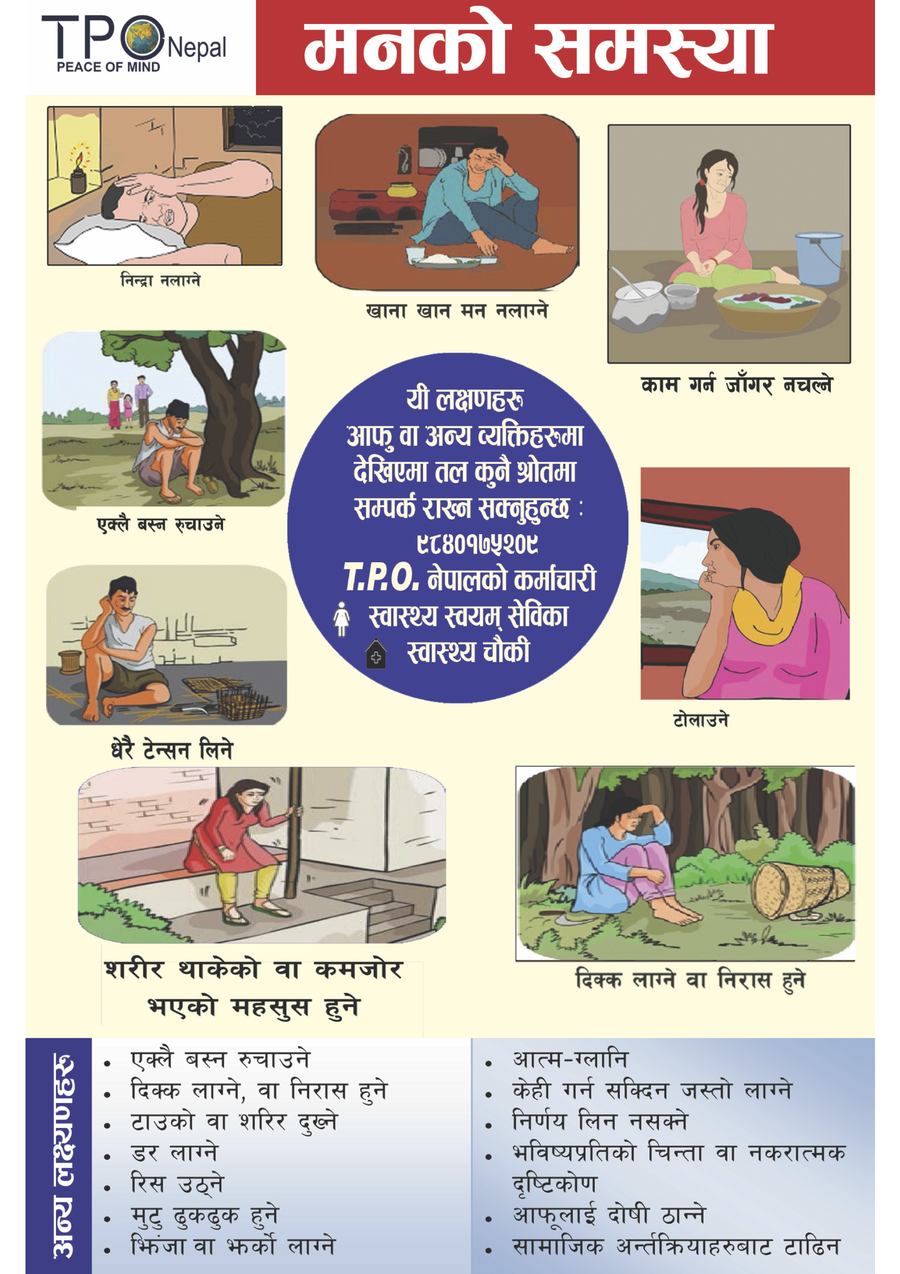

Although counsellors sometimes used the word ‘symptoms’, the lists they ran through did not derive from any formal diagnostic criteria for mental disorders. Instead, they were populated with local ‘idioms of distress’, well documented in anthropological and transcultural psychiatric work in Nepal (Nichter 1981; Sharma and van Ommeren 1998; Kohrt and Hruschka 2010; Chase and Sapkota 2017). Figure 1 offers an illustrated list of complaints that counsellors frequently mentioned. ‘Psychoeducational’ posters like this one were sometimes displayed in public places or distributed in communities by mental health NGO staff to help ‘raise awareness’ about when and where members of the public should seek help for ‘heart-mind problems’. In everyday interactions with clients and families, however, counsellors rarely referred to such materials or offered exhaustive lists of possible symptoms. Instead, they generated symptom lists on an ad hoc basis, flexibly tailoring their descriptions to the particular social contexts in which they worked and, at times, to individual illness trajectories.

Figure 1. An ‘Information, Education and Communication’ handout

publicly available in the resources section of TPO-Nepal’s website (Retrieved 15

September 2019 from http://tponepal.org/category/iec-materials/;

designed and published in Nepal and reproduced here with permission of the copyright

holder TPO-Nepal). The title reads ‘heart-mind problem’ [manko samasyaa] and viewers are

told they can contact TPO-Nepal, a female community health volunteer, or a health post

if they recognise any of these ‘symptoms’ in themselves or others (beginning top centre

and moving clockwise): not feeling like eating, having no interest in working, being

absent-minded/staring into space, being bored or frustrated, feeling your body is tired

or weak, ‘taking a lot of tension’, ‘liking to stay alone’, and not being able to sleep.

Additional symptoms listed at the bottom include the head and body hurting, feeling

fear, getting angry, heart palpitations, feeling irritated, guilt/remorse, feeling like

you can’t do anything, the inability to make decisions, anxiety and a negative view

towards the future, blaming oneself, and avoiding social interaction.

Figure 1. An ‘Information, Education and Communication’ handout

publicly available in the resources section of TPO-Nepal’s website (Retrieved 15

September 2019 from http://tponepal.org/category/iec-materials/;

designed and published in Nepal and reproduced here with permission of the copyright

holder TPO-Nepal). The title reads ‘heart-mind problem’ [manko samasyaa] and viewers are

told they can contact TPO-Nepal, a female community health volunteer, or a health post

if they recognise any of these ‘symptoms’ in themselves or others (beginning top centre

and moving clockwise): not feeling like eating, having no interest in working, being

absent-minded/staring into space, being bored or frustrated, feeling your body is tired

or weak, ‘taking a lot of tension’, ‘liking to stay alone’, and not being able to sleep.

Additional symptoms listed at the bottom include the head and body hurting, feeling

fear, getting angry, heart palpitations, feeling irritated, guilt/remorse, feeling like

you can’t do anything, the inability to make decisions, anxiety and a negative view

towards the future, blaming oneself, and avoiding social interaction.

Embracing pluralism

Importantly, gathering familiar complaints like those listed in Figure 1 under the loose heading of a ‘heart-mind problem’ did not rule out other possible groupings, labels, or explanations. The counsellors I interviewed all told me they avoided contradicting other readings of clients’ symptoms, and some counsellors had considerable confidence in shamanic and ritual practitioners. I discussed the matter at length with Krishna, the youngest counsellor I met in Sindhupalchok district. A serious and thoughtful student of social work in his early twenties, Krishna told me:

That shamanic ritual [jhaar-phuk] is also like a kind of counselling, it seems to me […] Whatever problems can be addressed through counselling, it has also happened that shamanic ritual can decrease them […] It is not appropriate for me to go into the community and say, ‘You shouldn’t believe in shamans.’

An important exception to this rule, Hari pointed out, was when families had already spent exorbitant sums of money on shamanic interventions to no avail, as was often the case in the relatively common and intractable instances of spirit possession among adolescent girls in Nepal (or ‘conversion disorder’, in the view of Nepali mental health professionals). Seale-Feldman (2019) has eloquently described how counsellors challenged rural communities’ understandings of affliction in such instances. Her account draws attention to the outer limits of the aspirational politics my interlocutors endorsed—that is, the point at which the ideal of beneficent coexistence with shamans breaks down.

Yet in the rural community-based counselling practices I observed, in contrast with short-term NGO-led interventions, there were additional social and structural reasons for embracing therapeutic pluralism. Counsellors lived in the same villages as the shamans serving their clients and maintained relationships with them as neighbours and sometimes, as in Kalpana’s case, kin. Moreover, in a context of busy schedules and dire resource constraints, clients who found relief through other avenues lessened the burden of care borne by counsellors—often young married women juggling numerous domestic responsibilities alongside their poorly remunerated professional duties (Chase et al. 2020). In Tara’s case, for example, Kalpana eventually declined to offer counselling; pointing to Tara’s claims of gradual improvement through prayer, she explained that she could not afford to spend time with clients already on the mend.

In my interlocutors’ cautious usage, then, the label of ‘psychosocial problem’ emphatically did not supplant other framings of affliction and nor did clients’ willingness to receive counselling mean they agreed with their counsellors about the nature of what ailed them; instead, the label functioned as a loose second-order concept or umbrella category that flexibly absorbed and accommodated other characterisations of suffering. What, then, did this loose reframing achieve?

Mobilising hope and care

Surendra was a portly middle-aged man who owned a small shop in a town on the highway. When I stopped by for a snack one afternoon we got to chatting and I learned that he had been employed as a psychosocial worker for just over a year. When I asked him how his first encounters with potential clients usually went, he told me that he too used the term ‘heart-mind-related illness’, and then elaborated:

First of all, we establish a relationship with the family and tell them about psychosocial problems: ‘This kind of problem can be like such and such […] After doing treatment it will be cured. Like other illnesses, you have to […] keep supporting them. By support I mean you have to continually show them love and kindness [daya maya]’.

Surendra’s account brings another key element of psychosocialisation to the fore: the assertion that care for heart-mind problems is both warranted and feasible.

Counsellors illustrated the importance of care by emphasising the disruptive effects of heart-mind problems in people’s lives. They pointed to physical and relational consequences that jeopardised not only an individual’s wellbeing, but their ability to work and provide for their family. Counsellors also challenged the normative moral judgments that might prevent families from seeing the suffering individual as worthy or deserving of care. Sushila, for example, explained:

We spread these kinds of examples, like, ‘After first starting from a psychosocial problem, that becomes depression, and if something bad happens then at the end that person can even come to the point of committing suicide. In our community, how many people have already committed suicide? And after they commit suicide, the community says, “This person is like this,” but they don’t ask what happened to him before’.

By framing suicide as a result of not who someone is but of what happened to them, Sushila actively redrew ‘the boundaries between conditions for which an individual is to be accorded responsibility, and those for which responsibility is to be located elsewhere’ (Rose 2006, 481).

A final cross-cutting element was the emphatic assertion that such problems could indeed be solved. Unsurprisingly, counsellors often emphasised the idea that psychosocial problems could be solved through counselling, using more familiar proxies such as ‘conversation’ [kuraakaani] or ‘giving counsel’ [paraamarsa]. Sushila, for example, went on to tell prospective clients:

So many things can be fixed through conversation […] how many things, if someone listens to them—if you have something to say and someone listens to that for you—how light your heart-mind will feel. And we listen to that for you. We do the work of listening for you and it is very confidential.

Invoking lay knowledge about the heart-mind’s suffering, Sushila and other counsellors reassured clients that such problems could be resolved with minimal social and financial cost.

Taken together, these strategies established new grounds for hope and action in the face of conditions that were often mysterious, disruptive, and intransigent. In the many cases where families had exhausted their patience and resources by the time they met a counsellor, psychosocialisation re-invoked the responsibility to seek care at the same time that it marked out new pathways for doing so.

Theorising translation in global mental health

Existing literature on translation in global mental health (GMH) focuses mainly on the challenges linguistic and cultural difference pose for research and intervention (van Ommeren et al. 1999; van Ommeren 2003; Snodgrass, Lacy, and Upadhyay 2017; Van Ommeren et al. 2000; Swartz et al. 2014). In this body of work, translation is understood as a process fundamentally concerned with meaning—that is, with generating representations that are both comprehensible and meaningful in a given social context. The present analysis explores the usefulness of a conceptualisation of translation informed by science and technology studies (STS), which additionally considers how representations are shaped by the desire to enlist support and cooperation (Callon 1986; Star and Griesemer 1989).

Clinicians involved in the GMH project of ‘scaling up’ are not merely charged with introducing new concepts and services in low-resource settings; they must also ensure the intended beneficiaries actually engage with them. In rural communities in Nepal, this means persuading people to invest precious time and energy in unfamiliar and potentially stigmatising forms of care intended to treat conditions accorded relatively low value. At any point, potential clients can (and often do) ‘refuse the transaction by defining its identity, its goals, projects, orientations, motivations, or interest in another manner’ (Callon 1986, 62).

The enrolment of clients in mental health and psychosocial services, we see clearly in counsellors’ accounts above, hinges on much more than dutifully conveying meaning; it calls for the translation of interests—that is, ‘the ideas or instructions [clinicians] purvey’ must be ‘translated into other people’s own intentions, goals and ambitions’ (Mosse 2005, 8). The care agendas of potential clients and their families in rural Nepal must be brought into alignment with those of frontline counsellors. This is no mere matter of tokenistic cultural sensitivity; it is fundamental to the production of ‘success’ in GMH projects (Mosse 2005). And as the growing literature on ‘demand-side barriers to care’ attests, achieving such alignment is no small feat (Patel 2014; Patel et al. 2018).

Psychosocialisation, as I saw it play out in Nepal, offers a new solution to this problem of translation, one that differs markedly from the medicalising approach of psychiatry. Instead of replacing existing illness categories and idioms of distress with a single authoritative diagnosis, it loosely repackages them in ways that shift constellations of hope and obligation, framing such suffering as requiring, worthy of, and amenable to the forms of care on offer. By grouping familiar complaints under the flexible, metaphorical umbrella headings of ‘wound’, ‘illness’, or ‘problem’ in the heart-mind, counsellors reconfigured the moral landscape of affliction without directly specifying its nature.

Yet as Star and Griesemer’s (1989) work reminds us, counsellors and laypeople in rural Nepal are only two groups of actors among many who must collaborate in order to realise the GMH ambition of extending services across low- and middle-income countries. [10] International donors, development organisations, the World Health Organization (WHO), researchers, government ministries, professionals of varied psy-disciplines, and service user advocates are also tied into these therapeutic projects, despite their often divergent understandings of what is at stake (Bemme 2018). The category of the ‘psychosocial problem’ facilitates this collaboration in much the same way as Star’s ‘boundary object’ (Star and Griesemer 1989; Star 2010).

On one hand, the definition of ‘psychosocial problems’ is vague in common use across the broader fields of global health, development, and humanitarian response. Critical social scientists have rightly drawn attention to the lack of operational definitions, the confusion between means and ends, and the blackboxing of complex mind/body/society relations it effects (Kohrt and Song 2018; Watters 2010; Pupavac 2002; Abramowitz 2014). Judging by the diversity of interventions implemented in its name, the category of ‘psychosocial problems’ might as well be defined as ‘suffering not otherwise being addressed’. Star’s work recasts this vagueness as the interpretive flexibility required for cooperation among so many diverse actors. In other words, it suggests psychosocial interventions may be gaining popularity not despite but precisely because of the lack of a unitary vision of the problems they set out to address.

On the other hand, the meaning of ‘psychosocial problems’ is relatively well-structured in its local use at specific sites. Counsellors’ accounts showed remarkable similarities, including the near-exclusive reliance on Nepali language proxies of a problem, sickness, or wound in the ‘heart-mind’ as well as the idioms of distress they populated these labels with. This local definition is now enshrined in culturally adapted counsellors’ training curricula that have been refined and formalised over a decade and adopted by leading NGOs in the sector.

Nepali psychosocial counsellors tack back and forth between these more- and less-structured definitions of ‘psychosocial problems’, enabling them to broker collaborations across geographic, disciplinary, and social distance. Able to speak in the internationally recognisable idiom of a ‘psychosocial problem’ to researchers, clinical supervisors, and the mental health specialists they refer to, they also have leeway to translate the object of their care in context-specific ways in their work with clients—ways that absorb, rather than challenge, other locally salient interpretations of suffering.

The practices of frontline psychosocial workers like those I interviewed are, increasingly, where the ambitions of GMH are brought into alignment with the care aspirations of intended beneficiaries and their families in diverse low-resource settings worldwide. Importantly, the translations these practitioners effect do not necessarily efface difference or produce agreement about the nature of affliction. We see a new discursive politics at work in these Nepali counsellors’ accounts in which authority is established not by unilaterally rejecting local discourses of affliction, but by mobilising capacious therapeutic objects that flexibly absorb and accommodate them. Generating meaningful anthropological critique in this new political terrain may require rethinking the theoretical lenses through which we have historically approached the globalisation of the psy-ences. [11]

Concluding thoughts for the critical anthropology of global mental health

A growing body of scholarship highlights the limitations of well-established paradigms of medical anthropological critique in the face of increasingly complex and self-reflexive global health interventions. This account joins a chorus of voices questioning the central place of medicalisation theory in anthropological analyses of the globalisation of the psy-ences. Recent work in this vein has highlighted the singular trajectories of medicalisation in different contexts (Han 2012), the potential for medicalisation to resocialise rather than desocialise suffering (Behrouzan 2015), and the limited persuasive power of attempts to medicalise ‘outside the narrow circles of biological psychiatry’ (e.g., Kitanaka 2008, 153). A recent special issue on the ‘global psyche’ calls for a move beyond ‘the hermeneutics of suspicion underlying much medicalization scholarship to ask what other modes of critique might be possible and useful’ (Béhague and MacLeish 2020, 8).

My analysis contributes to this conversation a portrait of a therapeutic practice that has begun to escape the logics of the ‘medical’ altogether. Psychosocialisation, as described by my interlocutors in Nepal, is not only distinct from medicalisation; it may represent the very undoing of medicalisation. Where psychiatric approaches have long sought to establish mental suffering as a medical problem amenable to pharmaceutical treatment, Nepali counsellors recast embodied suffering as a social problem amenable to relational forms of intervention. Where psychiatry has navigated the field of mental suffering using as its roadmap the medical model of diagnosis and treatment, psychosocial approaches relax the medical model’s grip on care. And compared with psychoanalytic approaches that have long been the Other of biomedical psychiatry (Béhague and MacLeish 2020), psychosocial interventions are mobile, brief, and affordable—easily transported across boundaries and delegated to laypeople after short targeted training courses.

Yet this is not the only story of psychosocialisation that can be told. Indeed, in Indian-administered Kashmir, the story runs directly counter my own: psychosocial counsellors have begun to adopt the forms and therapeutics of doctors in a bid to assert their legitimacy locally, ultimately reinforcing a medical model (Varma 2012). Likewise, the confluence of humanitarian ideals and Christian morals that shaped counselling practices in Liberia (Abramowitz 2014) is a far cry from the lay knowledge of the heart-mind mobilised by practitioners in Nepal as they worked to circumvent a normative morality that apportions blame to those suffering. This diversity, I have worked to show, is not an unintended by-product of globalisation; instead, it speaks to the flexibility that makes psychosocial interventions so readily globalise-able.

My analysis of psychosocialisation, then, does not support a sweeping critique of ill-defined therapeutic objects such as ‘distress’ and ‘psychosocial problems’ in global mental health (GMH). Indeed, when therapeutic objects function as ‘boundary objects’, ill-structured ‘global’ definitions necessarily tell us very little about the proliferation of more structured local meanings they abet. If we accept that translation strives for cooperation rather than consensus, the position that scaling up psychosocial interventions will have the same harmful or homogenising effects across diverse sites of implementation becomes as untenable as the position that it will yield uniformly positive outcomes. And it is for this reason that psychosocialisation cannot operate as new master concept for analysing global social change; at least, not in the way medicalisation long has.

Instead, meaningful critiques of psychosocialisation must be grounded in close attention to processes of translation in each new social setting. Ironically, the more sweeping and nebulous the therapeutic objects adopted at the level of global policy, the more precise, contextualised, and geographically specific our critiques must be. This is a task to which the anthropologist’s epistemological toolbox is particularly well suited; it requires mastery of multiple languages, a sensitivity to history and context, a concern with emic interpretations, and a commitment to crafting bespoke critical accounts at the expense of generalisability.

As others have noted (Abramowitz 2010; Varma 2012; Kienzler 2020), the practices of frontline clinicians working within transnational mental health projects offer rich ethnographic terrain for such investigations. Practitioners with a few days to a few months of training deliver a growing proportion of mental health and psychosocial care across the Global South, and there is an urgent need for a more robust conceptualisation of their roles and contributions. As the counsellors’ accounts above attest, these actors do far more than passively transport meaning or execute the wills of their superiors; they are ‘mediators’ in Latour’s (2005) sense, creatively and agentively transforming meaning with consequences that can never be predicted at the outset. If we continue to structure our critiques around the psychiatrists at the helm of the GMH endeavour—construing community workers as mere ‘handmaidens of biomedical expertise’ (Campbell and Burgess 2012, 381)—we risk reproducing clinical hierarchies that direly undervalue the labour of frontline workers worldwide (Maes 2015; Brodwin 2013; Chase et al. 2020).

In sum, as psychosocial interventions delivered through task-shifting continue to gain traction in GMH, ethnographies of frontline practice are more essential than ever to a critical anthropology concerned with the social and political consequences of ‘scaling up’. Research on the views, interests, and communicative strategies of frontline psychosocial providers across different sites has much to teach us about the implications of shifting GMH policies for those most marginalised from centres of power and expertise. Ethnographers might further consider engaging with frontline providers as co-investigators and social critics in their own right, designing studies around the difficulties and dilemmas community workers themselves deem most pressing. Such studies, my experience suggests, could provide valuable opportunities to make more incisive and impactful critiques of GMH practice while simultaneously challenging us to refine and develop medical anthropological theory.

Acknowledgements

This research would not have been possible without the partnership of TPO-Nepal (https://tponepal.org/). I am grateful to Dristy Gurung, Dr Kamal Gautam, Nagendra Luitel, Parbati Shrestha, Sujan Shrestha, Kripa Sidgel, and Sunita Rumba for their support and guidance during my fieldwork. Pia Noel, David Mosse, Christopher Davis, Michael Hutt, Joanna Cook, and Ian Harper provided valuable comments on earlier iterations of this article, and conversations with Dörte Bemme enriched it. I received financial support for my doctoral work from SOAS University of London, the University of Cambridge (Frederick Williamson Memorial Fund Grant), and the University of Edinburgh (Tweedie Exploration Fellowship). I also benefitted from a two-month research residency at the Brocher Foundation.

About the author

Liana E. Chase is an assistant professor of anthropology at Durham University. Her research sits at the nexus of anthropology and psychiatry, exploring the implications of social diversity and inequality for mental healthcare. Chase has a longstanding regional focus on the Nepal Himalaya, where she has been involved in anthropological research for over a decade. Her work has been published in a range of journals including The Lancet Psychiatry, Social Science and Medicine, Transcultural Psychiatry, and Global Mental Health. She is currently beginning fieldwork for a three-year ethnographic study of ‘Peer-supported Open Dialogue’, an innovative approach to mental healthcare being trialled in the UK's NHS.

Footnotes

-

All participant names and some identifying details have been changed to preserve anonymity. ‘Ashrang’ is a fictitious name for the rural municipality where I worked in Sindhupalchok district.↩︎

-

Star and Griesemer (1989) adopt the notion of interessement, developed to describe the process by which scientists recruit and maintain support from non-scientists, but go on to underscore the need to move beyond this dyadic conception to recognise a greater diversity of actors, each with their own concerns, worldviews, and entrepreneurial projects, who must be enlisted to see a given project succeed.↩︎

-

Star and Griesemer (1989) developed the concept of boundary objects with a view towards understanding how information is translated and managed within scientific enterprises. In a later piece, Star (2010) expands this definition to consider boundary objects that emerge in relation to work requirements more broadly. She also acknowledges that the word ‘boundary’ problematically suggests a fixed and clear line between incommensurable social worlds, when it should instead be read as a ‘shared space, where exactly that sense of here and there are confounded’ (idem., 603).↩︎

-

Ethical approval was obtained from the Nepal Health Research Council and SOAS University of London.↩︎

-

Exact population omitted to preserve anonymity.↩︎

-

Although a room was rented to house the psychosocial support centre, budget restrictions meant that its condition and location were poor. As a result, the vast majority of counselling took place in clients’ homes.↩︎

-

In accordance with the terms of my ethical approval, I did not observe any counselling sessions or interview current clients of the psychosocial support centre. My perspective on clinical encounters was therefore limited to what I learned from interviews with clinicians, former clients (considered recovered at the time of my fieldwork), and caregivers of current and former clients.↩︎

-

Although she does not speak English, Kalpana knew my project well enough to step in and clarify when my imperfect Nepali caused confusion or misunderstanding. I also had two bilingual research assistants in Kathmandu who transcribed audio recordings of my interviews in Nepali and checked my translations to English for accuracy.↩︎

-

During fieldwork, I was affiliated with the Transcultural Psychosocial Organization-Nepal (TPO-Nepal). TPO-Nepal is one of the largest and most active organisations in Nepal’s small mental health sector and the implementing partner for all four major GMH projects underway in the country (Seale-Feldman 2020a).↩︎

-

Star and Griesemer’s (1989) work develops a complex ‘ecological’ view of the distribution of power in large-scale projects, one that takes the conversation beyond the binary of scientists/experts imposing their visions on laypeople/non-experts to recognise the diversity of actors working on translations of their own at any given moment. They call this the ‘n-way’ nature of interessement.↩︎

-

I use this term to refer to ‘the disciplines and professions concerned with the human mind, brain, and behavior’ (Raikhel and Bemme 2016, 151), including but not limited to psychiatry, psychology, social work, neuroscience, psychotherapy (including psychoanalytic approaches), and psychosocial support.↩︎

References

Abramowitz, Sharon. 2014. Searching for Normal in the Wake of the Liberian War. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Abramowitz, Sharon. 2010. ‘Trauma and Humanitarian Translation in Liberia: The Tale of Open Mole’. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 34 (2): 353–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-010-9172-0.

Béhague, Dominique P., and Kenneth MacLeish. 2020. ‘The Global Psyche: Experiments in the Ethics and Politics of Mental Life’. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 34 (1): 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/maq.12570.

Behrouzan, Orkideh. 2015. ‘Medicalization as a Way of Life: The Iran-Iraq War and Considerations for Psychiatry and Anthropology’. Medicine Anthropology Theory 2 (3): 40–60. https://doi.org/10.17157/mat.2.3.199.

Bemme, Doerte. 2018. ‘Contingent Universals, Aggregated Truth: An Ethnography of Knowledge in Global Mental Health’. PhD thesis. Montreal: McGill University.

Bemme, Dörte, and Laurence J. Kirmayer. 2020. ‘Global Mental Health: Interdisciplinary Challenges for a Field in Motion’. Transcultural Psychiatry 57 (1): 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461519898035.

Brodwin, Paul. 2013. Everyday Ethics: Voices from the Front Line of Community Psychiatry. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Callon, Michel. 1986. ‘Some Elements of the Sociology of Translation: Domestication of the Scallops and the Fishermen of St. Brieue Bay’. Sociological Review Monography 32: 57–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.1984.tb00113.x.

Callon, Michel, and John Law. 1982. ‘On Interests and Their Transformation: Enrolment and Counter-Enrolment’. Social Studies of Science 12 (4): 615–625.

Campbell, Catherine, and Rochelle Burgess. 2012. ‘The Role of Communities in Advancing the Goals of the Movement for Global Mental Health’. Transcultural Psychiatry 49 (4): 379–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461512454643.

Chase, Liana E., Kedar Marahatta, Kripa Sidgel, Sujan Shrestha, Kamal Gautam, Nagendra P. Luitel, Bhogendra R. Dotel, and Reuben Samuel. 2018. ‘Building Back Better? Taking Stock of the Post-Earthquake Mental Health and Psychosocial Response in Nepal’. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 12 (44): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-018-0221-3.

Chase, Liana E., Dristy Gurung, Parbati Shrestha, and Sunita Rumba. 2020. ‘Gendering Psychosocial Care: Risks and Opportunities for Global Mental Health’. Lancet Psychiatry. Web. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30483-1.

Chase, Liana E. and Damayanti Bhattarai. 2013. ‘Making Peace in the Heart-Mind: Towards an Ethnopsychology of Resilience among Bhutanese Refugees’. European Bulletin of Himalayan Research 43: 144–166.

Chase, Liana E., and Ram P. Sapkota. 2017. ‘“In Our Community, a Friend Is a Psychologist”: An Ethnographic Study of Informal Care in Two Bhutanese Refugee Communities’. Transcultural Psychiatry 54 (3): 400–422. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461517703023.

Clark, Jocalyn. 2014. ‘Medicalization of Global Health 2: The Medicalization of Global Mental Health’. Global Health Action 7 (1): 24000. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v7.24000.

Cooper, Sara. 2016. ‘Global Mental Health and Its Critics: Moving Beyond the Impasse’. Critical Public Health, 26 (4): 355–358.https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2016.1161730.

Das, Anindya and Mohan Rao. 2012. ‘Universal Mental Health: Re-evaluating the Call for Global Mental Health’. Critical Public Health 22 (4): 383–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2012.700393.

Ecks, Stefan. 2020. ‘A Medical Anthropology of the “Global Psyche”’. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 34 (1): 143–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/maq.12569.

Fernando, Suman. 2011. ‘A “Global” Mental Health Program or Markets for Big Pharma?’ Open Mind 168 (22): 2353.

Han, Clara. 2012. Life in Debt: Times of Care and Violence in Neoliberal Chile. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Harper, Ian. 2014. Development and Public Health in the Himalaya: Reflections on Healing in Contemporary Nepal. London: Routledge.

Inter-Agency Standing Committee. 2007. IASC Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings. Geneva: IASC.

Jordans, Mark J. D., Nagendra P. Luitel, Emily Garman, Brandon A. Kohrt, Sujit D. Rathod, Pragya Shrestha, Ivan H. Komproe, Crick Lund, and Vikram Patel. 2019. ‘Effectiveness of Psychological Treatments for Depression and Alcohol Use Disorder Delivered by Community-Based Counsellors: Two Pragmatic Randomised Controlled Trials within Primary Healthcare in Nepal’. The British Journal of Psychiatry 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.300.

Jordans, Mark J. D., Nagendra P. Luitel, Brandon A. Kohrt, Sujit D. Rathod, Emily C. Garman, Mary De Silva, Ivan H. Komproe, Vikram Patel Id, and Crick Lund. 2019. ‘Community-, Facility-, and Individual-Level Outcomes of a District Mental Healthcare Plan in a Low-Resource Setting in Nepal: A Population-Based Evaluation’. PLoS Medicine 16 (2): e1002748.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002748.

Jordans, Mark J. D., Weitse A. Tol, Bhogendra Sharma, and Mark van Ommeren. 2003. ‘Training Psychosocial Counselling in Nepal: Content Review of a Specialized Training Program’. Intervention: The International Journal of Mental Health, Psychosocial Work and Counselling in Areas of Armed Conflict 1 (2): 18–35.

Kienzler, Hanna. 2020. ‘“Making Patients” in Postwar and Resource-Scarce Settings. Diagnosing and Treating Mental Illness in Postwar Kosovo’. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 34 (1): 59–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/maq.12554.

Kitanaka, Junko. 2008. ‘Diagnosing Suicides of Resolve: Psychiatric Practice in Contemporary Japan’. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 32 (2): 152–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-008-9087-1.

Kohrt, Brandon A., and James L. Griffith. 2015. ‘Global Mental Health Praxis: Perspectives from Cultural Psychiatry on Research and Intervention’. Kirmayer, J. Laurence, Robert Lemelson, and Constance A. Cummings, eds. Re-Visioning Psychiatry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 575–612.https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139424745.029.

Kohrt, Brandon A., and Ian Harper. 2008. ‘Navigating Diagnoses: Understanding Mind-Body Relations, Mental Health, and Stigma in Nepal’. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 32 (4): 462–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-008-9110-6.

Kohrt, Brandon A., and Suzan J. Song. 2018. ‘Who Benefits from Psychosocial Support Interventions in Humanitarian Settings?’ The Lancet 6 (4): 354–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30102-5.

Kohrt, Brandon A., and Daniel J. Hruschka. 2010. ‘Nepali Concepts of Psychological Trauma: The Role of Idioms of Distress, Ethnopsychology and Ethnophysiology in Alleviating Suffering and Preventing Stigma’. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 34 (2): 322–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-010-9170-2.

Kottai, Sudarshan R. and Shubha Ranganathan. 2020. ‘Task-Shifting in Community Mental Health in Kerala: Tensions and Ruptures’. Medical Anthropology 39 (6): 538–552. https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2020.1722122.

Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Maes, Kenneth. 2015. ‘Task-Shifting in Global Health: Mental Health Implications for Community Health Workers and Volunteers’. Kohrt, Brandon A., and Emily Mendenhall, eds. Global Mental Health: Anthropological Perspectives. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press. 291–308.

Mills, China. 2014. Decolonizing Global Mental Health: The Psychiatrization of the Majority World. New York City, NY: Routledge.

Mills, China and Suman Fernando. 2014. ‘Globalising Mental Health or Pathologising the Global South? Mapping the Ethics, Theory and Practice of Global Mental Health’. Open Access 1 (2): 188–202.

Mosse, David. 2005. Cultivating Development: An Ethnography of Aid Policy and Practice. New York City, NY: Pluto Press.

Nichter, Mark. 1981. ‘Idioms of Distress: Alternatives in the Expression of Psychosocial Distress: A Case Study from South India’. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 5: 379–408.

Patel, Vikram. 2014. ‘Rethinking Mental Health Care: Bridging the Credibility Gap’. Intervention: Journal of Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Conflict Affected Areas 12: 15–20.

Patel, Vikram, Shekhar Saxena, Crick Lund, Graham Thornicroft, Florence Baingana, Paul Bolton, Dan Chisholm, Pamela Y. Collins, Janice L. Cooper, Julian Eaton, Helen Herrman, Mohammad M. Herzallah, Yueqin Huang, Mark J. D. Jordans, Arthur Kleinman, Maria Elena Medina-Mora, Ellen Morgan, Unaiza Niaz, Olayinka Omigbodun, Martin Prince, Atif Rahman, Benedetto Saraceno, Bidkut K. Sarkar, Mary De Silva, Ilina Singh, Dan J. Stein, Charlene Sunkel, and Jürgen Unützer. 2018. ‘The Lancet Commission on Global Mental Health and Sustainable Development’. The Lancet 392 (10157): 1553–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31612-X.

Pathare, Soumitra, Alexandra Brazinova, and Itzhak Levav. 2018. ‘Care Gap: A Comprehensive Measure to Quantify Unmet Needs in Mental Health’. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 27 (5): 463–67. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796018000100.

Peters, Larry. 1978. ‘Psychotherapy in Tamang Shamanism’. Ethos 6 (2): 63–91.

Psychosocial Working Group. 2003. ‘Psychosocial Intervention in Complex Emergencies: A Conceptual Framework’. Edinburgh: Psychosocial working group.

Pupavac, Vanessa. 2002. ‘Pathologizing Populations and Colonizing Minds: International Psychosocial Programmes in Kosovo’. Alternatives 27: 489–511.

Raikhel, Eugene and Dörte Bemme. 2016. Postsocialism, the Psy-ences and Mental Health. Transcultural Psychiatry 53 (2): 151-175. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461516635534.

Rose, Nikolas. 2006. ‘Disorders Without Borders? The Expanding Scope of Psychiatric Practice’. BioSocieties 1 (4): 465–84. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1745855206004078.

Sapkota, Ram P., Kate Danvers, Wietse A. Tol, and Mark J. D. Jordans. 2007. Advanced Reader for Community Psychosocial Workers. Kathmandu: Sahara Paramarsha Kendra/USAID.

Sherchan, Surendra, Reuben Samuel, Kedar Marahatta, Nazneen Anwar, Mark H. van Ommeren, and Roderico Ofrin. 2017. ‘Post-Disaster Mental Health and Psychosocial Support: Experience from the 2015 Nepal Earthquake’. WHO South-East Asia Journal of Public Health 6 (1): 22–29. https://doi.org/10.4103/2224-3151.206160.

Seale-Feldman, Aidan. 2019. ‘Relational Affliction: Reconceptualizing “Mass Hysteria”’. Ethos 47 (3): 307–325. https://doi.org/10.1111/etho.12245.

Seale-Feldman, Aidan. 2020a. ‘Historicizing the Emergence of Global Mental Health in Nepal (1950–2019)’. Himalaya 39 (2): 29–43. https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol39/iss2/7.

Seale-Feldman, Aidan. 2020b. ‘The Work of Disaster: Building Back Otherwise in Post-Earthquake Nepal’. Cultural Anthropology 35 (2): 237–263. https://doi.org/10.14506/ca35.2.07.

Seale-Feldman, Aidan, and Nawaraj Upadhaya. 2015. ‘Mental Health after the Earthquake: Building Nepal’s Mental Health System in Times of Emergency’. Fieldsights. Web. 14 October. http://www.culanth.org/fieldsights/736-mental-health-after-the-earthquake-building-nepal-s-mental-health-system-in-times-of-emergency.

Sharma, Bhogendra, and Mark van Ommeren. 1998. ‘Preventing Torture and Rehabilitating Survivors in Nepal’. Transcultural Psychiatry 35 (1): 85–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461510368892.

Snodgrass, Jeffrey G., Michael G. Lacy, and Chakrapani Upadhyay. 2017. ‘Developing Culturally Sensitive Affect Scales for Global Mental Health Research and Practice: Emotional Balance, Not Named Syndromes, in Indian Adivasi Subjective Well-Being’. Social Science and Medicine 187: 174–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.06.037.

Star, Susan Leigh. 2010. ‘This Is Not a Boundary Object: Reflections on the Origin of a Concept’. Science Technology and Human Values 35 (5): 601–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243910377624.

Star, Susan Leigh, and James R Griesemer. 1989. ‘Institutional Ecology, “Translations” and Boundary Objects: Amateurs and Professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907–39’. Social Studies of Science 19 (3): 387–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631289019003001.

Summerfield, Derek. 2012. ‘Afterword: Against “Global Mental Health”’. Transcultural Psychiatry 49 (3–4): 519–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461512454701.

Swartz, Leslie, Sanja Kilian, Justus Twesigye, Dzifa Attah, and Bonginkosi Chiliza. 2014. ‘Language, Culture, and Task Shifting—An Emerging Challenge for Global Mental Health’. Global Health Action 7 (1): 23433. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v7.23433.

Tol, Wietse A., Mark J. D. Jordans, Sushama Regmi, and Bhogendra Sharma. 2005. ‘Cultural Challenges to Psychosocial Counselling in Nepal’. Transcultural Psychiatry 42 (2): 317–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461505052670.

Van Ommeren, Mark, Bhogendra Sharma, Suraj Thapa, Ramesh Makaju, Dinesh Prasain, Rabindra Bhattarai, and Joop de Jong. 1999. ‘Preparing Instruments for Transcultural Research: Use of the Translation Monitoring Form with Nepali-Speaking Bhutanese Refugees’. Transcultural Psychiatry 36 (3): 285–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/136346159903600304.

Van Ommeren, Mark. 2003. ‘Validity Issues in Transcultural Epidemiology’. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science 182: 376–78. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.182.5.376.

Van Ommeren, Mark, Bhogendra Sharma, R. Makaju, Suraj Thapa, and Joop de Jong. 2000. ‘Limited Cultural Validity of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview’s Probe Flow Chart’. Transcultural Psychiatry 37 (1): 119–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/136346150003700107.