During the spring of 2020, public messaging in the United States regarding COVID-19 conveyed the idea that pandemics and viral infections strike people from ‘all walks of life’ and that ‘diseases know no borders’. Corporations and media outlets disseminated the message that ‘we are all in this together’. While there might be some truth in these messages, they have also been challenged as existing social inequalities have been exposed by the impacts of COVID-19. The slogan ‘we are all in this together’—which apportions risk equally—is undermined when we consider the ‘social apparatus’ that informs people’s everyday lives. While people from some walks of life have been afforded the opportunity to telework, for instance, others have been required to report physically to workplaces. Given the tag ‘essential workers’, these people often work in places that carry greater risk of infection, partly because these spaces are some of the few remaining in which crowds continue to gather during the global pandemic. We use Lisa Marie Cacho’s (2012) formulation of the concept of ‘social death’ to offer a working theoretical model of essential workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. We engage with Cacho’s model of ‘social death’ to highlight the blurred lines, in times of crisis, between those rendered valuable and valueless (or disposable).

The Essential Crowd

Service Workers and Social Death in Pandemic Times

—

Abstract

‘These essential workers are out there putting themselves at risk to allow the rest of us to socially distance. And they come from disadvantaged situations, they come from disadvantaged communities.’

—Beth Bell, Global Health Expert,

University of Washington (quoted in Branswell 2020).

‘When there is noise and crowds, there is trouble.’

—Dejan Stojanovic, The Shape (2000).

‘As soon as a man has surrendered himself to the crowd,

he ceases to fear its touch. Ideally, all are equal there;

no distinctions count.’

—Elias Canetti, Crowds and Power (1984).

Introduction

During the spring of 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic hit and developed in the United States, public messaging about the situation—including U.S. presidential discourse—conveyed the idea that pandemics and viral infections strike people from ‘all walks of life’ (or, as Canetti phrases it above, ‘no distinctions count’) and, further, that ‘diseases know no borders’. Corporations and media outlets disseminated the message that ‘we are all in this together’. While some truth might reside in these messages, they have also been challenged as the impacts of COVID-19 have become clearer, exposing existing social inequalities. In fact, the slogan ‘we are all in this together’—which apportions risk equally—is undermined when we consider the social and economic apparatus that informs people’s everyday lives. While those from some socioeconomic backgrounds have been afforded the relative safety of teleworking, for instance, others, collected under the banner of ‘essential workers’, have been required to report to workplaces, some of them places of mass gathering.

The tag ‘essential workers’ encompasses a wide array of professions and jobs, and this breadth of category can serve to obscure the reality that many essential workers must report to workplaces which carry considerable risk of infection. This is partly because the spaces in which many essential workers perform their jobs contain some of the few remaining and sanctioned crowds within the unfolding global pandemic. That is to say, people performing certain jobs have been obligated to tend to the public face-to-face (within crowded spaces) or labour together in confined places (forming crowds themselves) under the banner of ‘essential’ activities. As we discuss below, in many instances this labour has taken place under less-than-ideal working conditions, in defiance of safety guidelines relating to crowds and social distancing. This becomes more gruesome when we realise that although the term ‘essential worker’ includes doctors, nurses, and other medical and professional personnel (that is, those who are arguably trained to operate during a pandemic), a large proportion of those falling into the essential worker category are some of the most grossly underpaid and unprotected workers within our economic structure. For us this raises the question: essential to whom and essential for what?

Unlike Canetti’s (1984) notion of a free-forming, organic crowd where a ‘man’ surrenders himself and where ‘all are equal’, the ‘essential worker’ category is manufactured and shaped by the economic forces and structures that summon its labour. This category has also been defined and formed by political motivation. For instance, in August 2020 the White House formally declared teachers to be essential workers ‘as part of their efforts to encourage schools around the country to reopen for in-person learning’ (Westwood 2020). Prior to this, teachers had not been considered, named or counted as essential workers.

Taking this into account, other questions emerge when trying to conceptualise essential workers as forming a crowd and being within it. These include: What happens when a category of workers is summoned and forced together during a global pandemic? What happens when a worker is unable to avoid the crowd at a time when crowded spaces can be lethal? And what happens when hundreds of thousands of people are forced to labour as part of the lethal crowd? We can invoke Stojanovic’s (2000) insight here that where there is noise and crowds, there is trouble. This has become a haunting truth as the pandemic continues to unfold; according to figures from the Economic Policy Institute, the essential crowd in the US numbers over 55 million workers (McNicholas and Poydock 2020).

In this article, we use Lisa Marie Cacho’s (2012) formulation of the concept of ‘social death’ to offer a working theoretical model of essential (crowd) workers as well as of the concept of social death in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. We use four specific, paired examples of essential workers operating during the early months of the pandemic and primarily consider those working in food processing plants and canneries, agricultural fields, warehouses, and grocery stores. Why these groups in particular? According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), ‘people from some racial and ethnic minority groups are disproportionately represented in essential work settings such as healthcare facilities, farms, factories, grocery stores, and public transportation’; they add that ‘some people who work in these settings have more chances to be exposed to the virus that causes COVID-19 due to several factors, such as close contact with the public or other workers, not being able to work from home, and not having paid sick days’ (CDC 2020). We use these examples of essential workers to illustrate and expand the concept of social death as we see it having taken place in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic. Before we delve into that discussion, we would like to expand on the concept of the essential worker crowd.

The essential worker crowd

Our aim in this article is to offer a theoretical analysis of the potential material consequences of State-sponsored rhetorical strategies vis-à-vis a subsection of workers deemed essential in the United States at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. From the start of the pandemic and during the multiple state-mandated lockdowns enacted in the United States, those considered to be essential workers were part of national discourse and State rhetoric. However, as discussed above, the term has been difficult to discuss and analyse, given the vast differences among the people who are included in the category. As Deepa Das Acevedo conveys, ‘[t]he single most important consequence of being deemed “essential” is that a worker enjoys the ability—or suffers the obligation—to continue working’ (2020, 2). This point is even more striking given that in April 2020 the unemployment rate in the United States reached 14.8 per cent—an unprecedented peak since data collection began in 1948 (Falk et al. 2021).

For the purposes of this article, we focus on a specific subsection of workers included within the category ‘essential worker’, and we refer to this subsection as the ‘essential crowd’. These workers share the following features and circumstances: they were allowed or required to work during lockdowns; their work was required to enable the rest of the social/economic system and infrastructure to continue operating; they often lacked access to adequate protection while labouring; and they were bound by economic necessity. Excluded from this are the subsections of essential workers exposed to the dangers of the pandemic by the moral imperatives involved within their work. For instance, medical professionals such as doctors, nurses, lab technicians, and first responders have an ethical imperative to provide care; those working in technology—such as IT and media workers—have a commitment to provide the public with information; and those working in the law are sworn to keep the justice system functioning. We continue the position of Das Acevedo, who maintains that although the safety of healthcare workers (to which we would add those in fields of technology and law) has been more or less protected, other essential workers have been left largely ‘vulnerable to their employers’ determinations regarding adequate personal protective equipment and social distancing measures’ (2020, 2). Das Acevedo continues, ‘In the United States more than in any other highly developed nation, one both works to live and works to have something to live for’ (idem, 5). This juxtaposition becomes especially ironic when workers are required to work during a deadly pandemic, for it is within this very context that the nature of the concepts ‘to live’ and ‘to live for’ are brought into question.

There are two other groups that we do not address in this article: non-essential workers working from home and workers who have lost their jobs because of the pandemic. Although each of these groups is worthy of discussion, we focus here on the essential workers that must routinely leave home—a presumed place of safety. As McCormack et al. put forward, regardless of the fact that ‘the label [essential worker] reflects society’s needs’, this ‘does not mean that society has compensated those workers for additional risks incurred on the job during the current pandemic’ (2020, 388). Das Acevedo (2020) addresses the fact that while essential labour is not a new concept, during the COVID-19 pandemic the ‘for whom’ shifted from ‘essential for the employer’ to ‘essential to society’. Missing from both conceptions of essential labour, according to Das Acevedo, is that from the worker’s point of view the labour is always essential. That is, work is essential to workers’ livelihoods and well-being. She explains that: ‘Essential labor replicates and exacerbates an attitude that has always been central to American work law: the idea that work should be measured, classified, regulated, and renumerated according to how much it benefits someone other than the worker’ (2020, 6). Das Acevedo points out that early in the pandemic it was made to seem that new ways of thinking about work would arise, with ‘essential labour’ emerging as ‘a seemingly disruptive concept’; however, ‘popular discourse and relevant law came to define essential labor as labor that is essential to society’ (ibid.). In so doing, the worker remained unprioritised.

In light of this insight we can add to our discussion of what transforms essential workers into crowds. Scholarly literature concerning crowds usually assumes that they come together or are put together coherently—with some exceptions, riots being the most notable (Surowiecki 2005, XIX). James Surowiecki takes this point further by claiming that there is wisdom in crowds, for a crowd’s ‘collective verdict’ contains ‘so much information’ (idem, 11). With the groups we discuss below, the essential workers are put together and placed at risk by ‘parallel’ labouring—that is, working closely together—which demonstrates that their collective fate is to be placed together for the benefit of society or the nation.

Looked at somewhat differently, the ‘we’ in the slogan ‘we are all in this together’ serves to make these workers part of a national collective. In this way, we can consider them to be ‘imagined’, in line with Benedict Anderson’s (2016) concept of an ‘imagined community’. Anderson articulates a constituted nation, through nationalism, as an imagined community and suggests that its members ‘will never know most of their fellow members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each other lives the image of their communion’ (2016, page). Anderson adds that communities are to be distinguished not by their falsity or authenticity but by the style in which they are imagined; he states that, ‘regardless of the actual inequality and exploitation that may prevail in each, the nation is always conceived as a deep, horizontal comradeship’ (idem, 6).

Conceived of as being akin to an imagined community, essential workers can be viewed through the concept of the nation as follows: members of the (imagined) essential crowd labour in synchronicity or communion without knowing one another and in doing so, they keep the nation’s population well-stocked and fed; they are distinguished by design as a self-sacrificing crowd; and the spectre of (willing) death marks the limited imaginings that shape public perceptions of this category of workers.

Importantly, Kevin Vasquez (2021) points out that the characterisation of essential workers as heroes by corporate leaders and political figures has often been self-serving. Vasquez states, ‘Beneath a hollow verbal appreciation [of essential workers] lurked a different reality. By calling workers ‘essential’ and turning them into heroes, their deaths became justified’ (2021, page). Vasquez maintains that ‘The language of the “essential worker” was cynically appropriated by corporations … to launder their responsibility and to rationalize the coercive social order that compelled underpaid workers to surrender their bodies and health for corporate profits’ (ibid., page). This appropriation, he writes, was enabled by politicians and mass media, which ‘compelled the working class to bear a greatly disproportionate share of the burden’ (ibid., page). Vasquez continues, ‘Essential workers, packed into crowded restaurants, factories, and grocery stores, did not, generally speaking, receive unemployment benefits, increased pay, paid sick leave, or better working conditions during the pandemic’. In fact, he emphasises, ‘the workers deemed most critical to the continued functioning of our society are also often the most mistreated and worst paid’ (ibid., page). These workers have routinely occupied positions of precarity.

Methodologically, in our discussion below we rely on data and reports that were appearing as we initiated this article, at a point early in the pandemic and during state-mandated lockdowns. While we did not conduct interviews with members of the groups we consider, many of the reports we cite below did rely on first hand accounts by workers concerning their treatment and labour conditions. Important to note is that the category ‘essential worker’ has a legal history that has, perhaps ironically, contributed to the precarious labour conditions of these very workers. While we do not invoke this history in detail in this article, we do wish to acknowledge that the legal domain itself has often been complicit in the precarity of many ‘essential workers’. Thus these workers are already in a disadvantaged position before a pandemic strikes. With these points in mind, we proceed to a discussion of four different groups within the essential crowd.

Food processing and agricultural fields

The Economic Policy Institute calculates that there are close to 11.4 million ‘food and agriculture’ workers in the United States, making up 20.6 per cent of the essential workers category (McNicholas and Poydock 2020). According to the Food and Environment Reporting Network (FERN), by November 2020, 548 meatpacking and 663 food processing plants across the United States had confirmed cases of COVID-19. At that time, 49,240 meatpacking workers and 13,242 food processing workers had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, and 253 meatpacking workers and 44 food processing workers had died of the disease (Douglas 2020).

The numbers alone, although important, do not convey the stories or context behind them. We would therefore like to briefly contextualise the numbers provided by FERN by outlining three high-profile cases involving food processing companies as they emerged in the U.S. during the summer of 2020: namely, three COVID-19 outbreaks within Pacific Seafood in Oregon, one among workers headed to work in Alaska for North Pacific Seafoods, and another at Foster Farms in California.

On 8 June 2020, the Salem Statesman Journal reported that Pacific Seafood, a processing plant in Newport, Oregon, had 124 confirmed positive cases (Barreda and Urness 2020). The company, which temporarily closed all five processing plants in the area (Fisher 2020), was then hit twice more the following September. One of these later incidents, at the beginning of the month, affected at least five employees in their Coos Bay, Oregon facility (Salmon Business 2020). The second incident occurred a few weeks later in Warrenton, Oregon, and involved nearly a hundred confirmed cases (Welling 2020). Pacific Seafood vowed to resume operations in their facilities as soon as they were ‘able to confirm the safety of our team members, fleet, and community … [and] resume all existing protocols … that go above and beyond current CDC guidance including sanitation, face coverings worn by all workers, plastic face shields and daily temperature checks’ (Barreda and Urness 2020).

In June 2020, the Associated Press released a story about 150 cannery workers being trapped in a Los Angeles hotel after three of them tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. The workers had been taken to the hotel for testing as they were en route (some from Mexico and others from Southern California) to a cannery owned by North Pacific Seafoods in Alaska. It was reported that all 150 workers were asked to remain confined in a small hallway while they were being tested, and that they shared pens when filling out forms. After the confirmed cases, all workers were forced to quarantine in rooms of the hotel without pay. The workers sued North Pacific Seafoods for false imprisonment, non-payment of wages, failure to pay minimum wages and overtime, negligence, and unlawful business practices (Associated Press 2020).

In August 2020, ‘Foster Farms announced that it would … temporarily close one of its poultry plants in Livingston, California’ after an outbreak that killed eight workers (Lin 2020). In addition to the eight deaths, ‘at least 392 plant employees tested positive for the virus’ (Lin 2020). This outbreak was declared ‘one of the largest occupational fatalities experienced during COVID-19 in the state of California’ and described as ‘significantly a big deal’ by Merced County Public Health Director, Dr Rebecca Nanyonjo-Kemp (Lauten-Scrivner 2020). According to reporting by the Merced Sun-Star, the county’s Department of Health ordered Foster Farms to meet the following requirements before reopening the plant: before they could report to work, all employees had to receive two negative results from COVID-19 tests taken no more than seven days apart; physical alterations to the workplace were required to ensure adequate social distancing for break spaces and areas of potential congregation; all facilities had to undergo an extensive deep clean by an external provider; and safety training and communication had to be provided to employees in English, Spanish, and Punjabi. Foster Farms responded that they would implement the ‘guidelines throughout the pandemic but could not protect workers exposed in the greater community’ (Merced Sun-Star 2020).

These three examples offer a brief illustration of conditions in which workers in the food and agriculture sector operated during the early stages of the pandemic, as reported by mainstream media outlets. As these accounts describe, working conditions that were commonly found included closed and perhaps poorly ventilated quarters and it was in these workplaces that dramatic outbreaks took place. The fact that the workers on their way to Alaska were required to quarantine in Los Angeles without pay also reveals that their work has been viewed as essential only insofar as they are willing or required to expose themselves to the virus.

Although working mostly outdoors rather than inside, the working conditions of farmworkers have also shown their vulnerability to infection. Comprising part of the 20.6 per cent ‘food and agriculture’ essential crowd, farmworkers’ working conditions are complicated by their migrating patterns and living conditions. According to the Economic Policy Institute, agricultural work ‘relies on approximately 220,000 workers on seasonal H-2A work visas and another estimated 1.5 million undocumented workers largely from Mexico and other Latin American countries’; this reliance on seasonal and undocumented workers, who experience precarious working conditions, ‘leaves workers with few protections and exposed to the virus’ (Reiley and Reinhard 2020).

The precarity of this group is reflected in the conflicting numbers concerning positive cases. On 24 September 2020, The Washington Post reported that a study conducted by Purdue University in collaboration with Microsoft found that 125,000 farmworkers around the United States ‘have tested positive for the coronavirus, as of September 22’ (Hayes 2020). However, Jayson Lusk, one of the Purdue investigators, suggested that this number may not reflect the reality of the situation, ‘as it does not include part-time and temporary workers’ (Reiley and Reinhard 2020). The researchers arrived at this estimate by applying ‘the county-by-county rate of the infection’s spread to the number of farmworkers and farmers in those counties’ (Hayes 2020). In November 2020, however, FERN disclosed that 267 farms and production facilities had had confirmed cases of COVID-19, that 11,137 farmworkers had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, and that 39 farmworkers had died because of the disease (Douglas 2020). This circumstance is situated within an exploitative history of migrant labour within the United States. Anthropologist Seth Holmes has discussed, for instance, the embodied symbolic violence that connects racism and economic exploitation within our food system (2013). Importantly, this is a violence and exploitation that has been rendered invisible by and within this very system.

Regardless of estimates and actual cases, a few points of commonality can be noted as putting farmworkers at risk. The Washington Post reported that farmers, or those that employ or contract farmworkers, sometimes do not allow their workers to get tested. According to their report:

In Yakima County, Washington, some fruit orchard owners declined on-site testing of workers by health departments at the height of harvest season even as coronavirus infections spiked. In Monterey, California, workers at some farms claimed foremen asked them to hide positive diagnoses from other crew members. And in Collier County, Florida, health officials did not begin widespread testing of farmworkers until the end of harvest, at which point the workers had already migrated northward (Reiley and Reinhard 2020).

According to the National Center for Farmworker Health (NCFH), ‘many [farm]workers fear testing for COVID since a positive test may mean a permanent job loss’ (NCFH 2020). However, testing is not the only issue. A study conducted by a partnership of ten worker organisations from California, Oregon, and Washington found that ‘workers employed by farm labor contractors may be less likely to receive PPE [personal protective equipment] from their employer’ (NCFH 2020). The Center also pointed out that ‘overcrowded and substandard housing conditions are a major concern for the potential of COVID-19 to spread through agricultural worker communities,’ as ‘a single building may house several dozen workers or more, who often sleep in dormitory-style quarters, making quarantining or social distancing efforts difficult if not impossible’. In addition, ‘limited access to restrooms and sinks, at home and in the field, may complicate hygiene prevention efforts’ (NCFH 2020).

Problems faced by those working on farms and those working in food processing plants converge on the issue of employers not appearing to take seriously the risks to which workers are exposed. This lack of care is compounded by poor pay, since Black and Latinx essential workers in food and agriculture are the lowest paid of essential workers, with median hourly wages of $12.59 and $13.05 respectively. This compares with $16.80 and $15.99, respectively, for Black and Latinx nonessential workers (McNicholas and Poydock 2020). In this regard, an awareness of race/ethnicity and social class informs how risk has been apportioned during the pandemic and via the category ‘essential worker’. While the nation has always relied on farm and migrant labour, explicitly categorising the work these individuals do as ‘essential’ has made work visible to a general public for which it is often invisible. At the same time, the danger of the work has been heightened for the workers themselves.

Warehouses and grocery stores

Also according to the Economic Policy Institute, there are 3.9 million essential workers who are working in the ‘transportation, warehouse, and delivery’ sector of the economy—comprising 7.2 per cent of essential workers as a whole in the U.S. Like those working in food processing plants, workers in warehouses and fulfilment centres work indoors and in potentially crowded spaces. Within this context, protective measures are important. However, a study conducted by the University of Berkeley’s Shift Project showed that while 49 per cent of warehouses and 56 per cent of fulfilment centres have made gloves available to their employees, only 10 per cent of warehouses and 7 per cent of fulfilment centres require employees to wear them. Face masks are less available: according to the study, only 17 per cent of warehouses and 14 per cent of fulfilment centres have provided these to their employees, and only 5 per cent and 12 per cent, respectively, require employees to wear them (Schneider and Harknett 2020).

In May 2020, as it was projected that Jeff Bezos would become the world’s first trillionaire by 2026, complaints about his company’s treatment of warehouse workers intensified (Molina 2020). The month began with Amazon warehouse workers, along with workers for other big companies such as Instacart and Target, organising and striking to advocate for ‘more access to protective gear like masks and gloves, extended time off to recover from sickness, and higher pay’ (Ghaffary 2020). In response, Amazon created a multimedia campaign driving ‘home a message to customers that keeping the “retail heroes” in its warehouses safe’ was its top priority (Ghaffary and Del Rey 2020). The conditions of workers in such warehouses have been addressed by anthropologist and activist David Graeber (2013), who highlights the positions of various temporary and gig workers as tenuous, low-paid, and benefit-less. As Graeber states, ‘Real, productive workers are relentlessly squeezed and exploited’ (2013, page). And while some workers exist in downsized and fragile spaces, others (the corporate top or ‘ruling class’) secure unprecedented levels of economic wealth and comfort (Graeber 2013). In the view of Vasquez, the very labelling of essential workers as ‘heroes’ did not emerge from the workers themselves—these workers ‘did not ask to be “heroes”’ (2021). Instead, use of this language has primarily worked to justify their perilous placement and labour and to benefit companies and their executives.

On 1 October 2020, CNBC reported that ‘between 1 March and 19 September, Amazon counted 19,816 presumed or confirmed COVID-19 cases across its roughly 1.37 million Amazon and Whole Foods Market front-line employees across the U.S.’ (Palmer 2020). These cases, of course, were not among its corporate workers, who were all allowed to work from home, but among its warehouse and retail workers, who must report to and operate in their designated work sites (Ghaffary and Del Rey 2020).

The pandemic increased the reliance on e-commerce for those staying at home (Cowan 2020), so much so that according to Tech Crunch it ‘has accelerated the shift away from physical stores to digital shopping by roughly five years’ (Perez 2020). Consequently, Amazon and other e-commerce businesses have experienced a dramatic increase in orders and, in parallel, a greater reliance on their employees ‘to sort, package, ship and deliver goods’ to meet the increased demand (Cowan 2020). Thus, the increase in demand has also led these businesses to increase the number of people working in ‘warehouses and fulfilment centers where that work can be done’ (ibid.). According to a recent analysis by the employee activist group AECJ (Amazon Employees for Climate Justice), ‘80 per cent of Amazon’s U.S. warehouses are located in zip codes that have a higher percentage of Black, Latinx, and Indigenous people than the regional average’ (Ghaffary and Del Rey 2020).

Of course, Amazon warehouses have not been the only ones hit by COVID-19, and most companies that engage in e-commerce have had to adjust to accommodate demand. Another example of this is Walmart, the biggest retail company in the United States, which during the first three months of the pandemic saw a 97 per cent increase in e-commerce (Perez 2020). At the beginning of April 2020, a Walmart warehouse in Bethelem, Pennsylvania, reported nine employees testing positive for the virus in less than a week (Harris 2020). A month later, a Walmart store in Worcester, Massachusetts, had to be temporarily closed after 81 employees tested positive (White 2020). And a month after that, a Walmart distribution centre in Loveland, Colorado, reported ‘27 positive cases with another half dozen “probable” cases’ (Ferrier 2020).

As well as having to work under similar conditions as those described above, grocery store workers must also deal with customers who interact with them when they are on the shop floor. This is true for cashiers, cleaning staff, managers, shelf stackers, and others. The difficulty here is compounded by other factors such as how well ventilated the building is, how many people are allowed in the building at any one time, whether the store provides personal protective equipment (PPE) for its employees, and whether it has rules about social distancing and is able to enforce them. According to a study, ‘workers in customer facing roles [like cashiers] were five times more likely to test positive than their colleagues in other types of roles… [and] those in supervisory roles were six times more likely to do so’ (BMJ 2020).

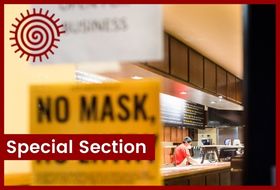

In a CBS News interview, Rachel Fournier, a cashier at a grocery store in California, identified the two main problems facing grocery store workers. One of these is crowds: she described how ‘stores are getting more crowded as people stock up ahead of the holidays, or as customers prepare for a shutdown’. The second problem she identified is a lack of social distancing and protection, saying that ‘efforts to limit traffic are not working, and there is no effort to ensure customers properly wear masks’ (Gibson and Ivanova 2020). In a September 2020 interview for The Guardian, a grocery store worker in Seattle, Washington, described how: ‘Customers are becoming crazy, sometimes violent when asked to wear a mask and we aren’t allowed to give out free masks due to the drama and hostility’ (Sainato 2020).

As Serina Chang et al. (2020) maintain, ‘the COVID-19 pandemic dramatically changed human mobility patterns’, which is to say the disease changed the way society ‘crowds’. In their research conducted in the Chicago, Illinois area, they found that ‘from March 1–May 2, 2020 … a majority of predicted infections occurred at a small fraction of what they call “superspreader” POIs [points of interest, i.e. places that people still frequented in relatively large numbers]’ (ibid.). In fact, the researchers found that ‘in the Chicago metro area, 10% of POIs accounted for 85% of the predicted infections at POIs’ (ibid.). More importantly, the researchers found, ‘certain categories of POIs also contributed far more to infections’—one of these being grocery stores.

Even as certain superspreader spaces such as grocery stores have been subjected to protocols aimed at minimising crowds and the risks that they carry, such mitigation efforts have been both uneven and discretionary (that is, enacted only if required by local officials or presented as ‘advisory’ only). In addition, these settings are by their very nature less likely to afford an opportunity to avoid the ‘three Cs’: closed spaces with poor ventilation, crowded spaces, and close-contact settings (Aschwanden 2020). In fact, according to Marc Peronne, President of the United Food and Commerical Workers Union, by November 2020, ‘350 of his union’s members had died from COVID-19, including 109 grocery store employees’ (Jones 2020). Peronne added that ‘more than 48,000 members have become ill or been exposed to the virus [while working]’ (Jones 2020). He was also adamant that these numbers could be much higher as ‘major retailers refuse to disclose how many of their workers have become sick or have died … with the union relying on local reports to piece together the figures’ (Gibson and Ivanova 2020). It is also worth noting that ‘profits soared an average of 39% in the first half of the year at supermarket chains and other food retailers due to the pandemic, although frontline workers reaped little or no benefit’ (Selasky 2020).

The essential crowd and social death

COVID-19 marks the most serious epidemic for the United States since the 1918 influenza pandemic. This is a medical and epidemiological reality. But the current pandemic also has a social reality that involves valued and devalued bodies and reveals much about the inequalities that structure U.S. contemporary society and the positioning of its people. First, as mentioned above, we can identify those who can work from home and contrast them with the crowd that must leave their homes to work. Second, we can note that many of those who must work outside the home, although bestowed the label ‘essential’, also form the crowd that society seems willing to sacrifice. Or, at least, the crowd they form is one that society appears comfortable to ask to make sacrifices for the benefit of the nation (and, by extension, for corporations and their leaders).

While providing a genealogy of the category ‘essential worker’ in light of the current pandemic, sociologist Andrew Lakoff remarks that the category has been open to ‘interpretive flexibility’, stating that ‘the category of “essential” could be understood as a new form of social classification, one that interacted in complex ways with existing forms of social inequality’ (2020). The interpretive reflexivity to which Lakoff alludes connects to the notion of the imagined crowd we discussed above, and the classification of essential workers—as it interacts with social inequality—leads us to Cacho’s discussion of social death.

In her work on social death, Cacho (2012) usefully develops a link between human value and State-sanctioned violence. The author ties her articulation of social death to the law, and while analysing the essential crowd we can extend the articulation of social death to general practices by the State (through federal and state executive orders and CDC guidelines), as well as to those that are directly connected to the law; or, more specifically, to the legal practices that have regulated labour and workers during the pandemic. The U.S. Department of Labor’s (DOL) statement on workers’ protections during the pandemic is one important example. According to its website:

The Wage and Hour Division is committed to protecting and enhancing the welfare of workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Federal laws, including the Fair Labor Standards Act and the Family and Medical Leave Act, provide critical worker protections regarding wages and hours worked and job-protected leave during the pandemic (U.S. Department of Labor 2021).

The question is: Have employers followed the dictates of these protections? From the examples we discussed above involving the essential crowd, the answer appears to be not always and not fully. Perhaps more significant is the fact that employers have often enjoyed an abstract benefit from the caché gained by employing ‘essential workers’ carrying out ‘essential work’ while in practice failing to deliver appropriate protections for these very workers. Importantly, the DOL’s statement does not specifically address protective working conditions during the pandemic, such as the need for PPE and masks, and the role of social distancing. In this respect, its protective capacity for workers has been weak. In addition, the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 explicitly excludes many agricultural workers; to invoke it during a pandemic acts to further marginalise, rather than protect, these workers.

For Cacho, devalued bodies are ‘ineligible for personhood’, mainly because they are ‘illegible’. In fact, she continues, devalued bodies ‘never achieve, in the eyes of others, the status of “living”’ (2012, 7). Devaluing bodies is both State-sanctioned violence and a form of social death. During the COVID-19 pandemic, as the realities of those being most affected came to light, it became clear that the essential worker crowd was simultaneously applauded and placed at great risk. Their labour was regarded as crucial to the maintenance of society and the nation, while the workers often did not experience sufficient safeguarding of their lives and wellbeing. Andrea Frantz has referred to these workers as ‘essential, but expendable’ (2020). For instance, despite the statement by the DOL that addressed wages, working hours, and leave, workers had no legally enforceable right to testing, PPE, hazard pay, or social distancing in workplaces.

Public celebration of ‘essential workers’ has taken place at the same time as the actual circumstances of those working within this category have been dismissed or downplayed. To illustrate this point, we offer the following examples. In July 2020, a study reported that 31 per cent of Americans believed ‘that the COVID-19 death toll [was] less than officially reported’ (Durkee 2020). A few months later, in a rally in Ohio during September 2020, as the United States approached 200,000 deaths due to the virus, President Trump told the crowd that COVID-19 ‘affects virtually nobody’, concluding that the virus ‘[is] an amazing thing’ (Rupar 2020). For those internalising such messages, 200,000 dead bodies were deemed ‘virtually nobody’.

This point speaks to the potential impact of language and rhetoric around the virus and its connection to those being asked or told to work within its sphere. In a survey conducted at the time of President Trump’s statement, approximately 40 per cent of respondents reported that they believed the COVID-19 fatality rate was widely exaggerated (Henley and McIntyre 2020). Minimising actual deaths and denying the impact of a virus that spreads quickly within crowds exacerbated the lack of care towards many essential workers and facilitated their dangerous working conditions. That is, the widespread belief in an exaggeration of the seriousness of the pandemic made lack of care towards essential workers more socially acceptable; it perhaps also encouraged employers to fail in their duties of care.

We engage with Cacho’s (2012) model of ‘social death’ to highlight the blurred lines, in times of crisis, between those who are protected and those who are pushed into harm’s way. Within this model, we can see that ascriptions of value have intersected with categories of social import such as race/ethnicity and social class. Cacho understands these ascriptions as ‘ways of knowing’ (2012, 2). According to the Economic Policy Institute, 45 per cent of essential workers in the United States are non-white. Of these, 21 per cent are Latinx and 18% are Black (McNicholas and Poydock 2020). Twenty-nine per cent of essential workers are educated to high school level; 10 per cent to a lower level (McNicholas and Poydock 2020).

Yen Le Espiritu’s (2003) notion of ‘differential inclusion’ is also helpful to consider here. Espiritu specifically uses ‘differential inclusion’ to discuss U.S. colonisation of the Philippines, but the concept can also be usefully applied to marginalised groups that are ‘deemed integral to the nation’s economy, culture, identity, and power—but integral only or precisely because of their designated subordinate standing’ (2003, 41–42). The fact that service workers (such as warehouse workers, food processing workers, farmworkers, and grocery store cashiers) were all deemed ‘essential workers’ with the onset of COVID-19-related shutdowns during the spring of 2020 illustrates that, as Espiritu maintains, inclusion does not preclude subordination. Within the narrative and public policy informing the response to COVID-19, many essential workers have been socially neglected even as they have been elevated as pandemic heroes. These workers have been both ubiquitous in public discourse and illegible in their precarity. This contradictory positioning has allowed employers to disregard worker safety in addition to making other manoeuvres that have not benefited those doing this work.

In our epigraph, Beth Bell states that ‘these essential workers are out there putting themselves at risk to allow the rest of us to socially distance’ (YEAR, quoted in Branswell 2020). This statement acknowledges that essential employees often have not been able to engage in social distancing—one of the pandemic safety pillars, especially in its early stages—like ‘the rest of us’, a position with which we agree. However, this statement also engages with an erroneous idea that essential workers are ‘putting themselves at risk’, since this phrasing implies that these workers have been afforded a choice. When the choice is between being able to feed and house themselves and their families or not, one could argue that there is no choice. Many essential workers are at risk because our economic and social structures make it impossible for them not to be at risk. They are effectively positioned as being differentially included.

Conclusion

In June 2020, three months into the pandemic in the United States, The Guardian reported that ‘nearly 600 healthcare workers’ had died of COVID-19 (Jewett, Bailey, and Renwick 2020). This tally was kept by Lost on the Frontline, an initiative established by The Guardian and Kaiser Health News (KHN) that aims ‘to count, verify and memorialize every healthcare worker who dies during the pandemic’, including ‘doctors, nurses and paramedics, as well as crucial healthcare support staff such as hospital janitors, administrators and nursing home workers’ (Jewett, Bailey, and Renwick 2020). Although we have not discussed healthcare workers in this article, we would like to point out the vast differences in positionality among those included within this category. For instance, hospital janitors might be both more likely to be exposed to the virus and to be rendered ‘illegible’ than other healthcare workers in different roles.

By the time the festive season approached in 2020, alarm bells sounded regarding the treatment of essential workers in retail and grocery stores with the anticipation of the arrival of unwieldy crowds of customers looking to do their holiday shopping. According to ‘leaders and members of the United Food and Commercial Workers Union, which represents more than 1 million food, retail and meatpacking plant workers’, by November 2020 ‘many major employers [had] grown lax, cutting wages and protections put in place when the coronavirus first began to spread in the spring’ (Jones 2020). On 2 December 2020, CDC Director Dr Robert Redfield stated to those attending ‘an event hosted by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’ that ‘the United States could start losing around 3,000 people—roughly the number that died in the attacks of September 11, 2001—each day over the next two months’. He added that the season between December 2020 and February 2021 was likely to be ‘the most difficult time in the public health history of this nation’, anticipating close to 450,000 deaths ‘from this virus’ by the month of February (Heavey 2020).

Considering who have been able to work from home during the pandemic and who have been required to leave their homes to work, we can conclude that not all ‘walks of life’ have been equally positioned within the social structures that have informed the pandemic, despite the mantra of us being ‘all in this together’. Moreover, the bodies and lives of those who have been pushed, by their very positioning, to leave the confines of their homes have also been undervalued in many respects by our society.

As we finished writing this article, the 2020 festive season was well underway and the United Food and Commercial Workers International (UFCWI) President Marc Perrone stated, ‘America’s essential workers are facing a holiday season of unparalleled danger as COVID-19 cases explode across the country. With more than 1 million new COVID-19 cases in the past week, and deaths spiking to unprecedented levels, we are entering what could be the deadliest phase of this pandemic for millions of America’s essential frontline workers’ (Selasky 2020). This is where Cacho’s (2012) articulation of social death manifests once again, as she focuses on those who have been both excluded from legal protections and criminalised. We have focused on those who, although not criminalised, have been excluded from substantive work protections and thereby rendered expendable—expendable by a society for whom they must work but that devalues the circumstances and conditions of that work while simultaneously referring to them as ‘heroes’.

Finally, as the pandemic has continued to unfold, the focus on ‘essential workers’ has begun to recede from headlines. Frantz (2020) states, ‘Evidently, some are “essential” when it’s politically expedient. And when it’s not, well, the label and circumstances can change dramatically’. And Zachary Jaggers (2020) has highlighted the ‘disconnect between how some low-wage workers [have been] described and their experiences on the ground’, stating that ‘discussions ought to be centered on how the people on the front lines are affected, and how to best ensure they’re well-compensated and protected’. We agree with Jaggers and would urge that attention continue to be paid to the category ‘essential worker’ as the pandemic continues. This attention must address the question of who benefits from essential labour, and how workers themselves are affected.

Acknowledgements

Add (optional, up to 150 words).

About the authors

Mary K. Bloodsworth-Lugo is professor of comparative ethnic studies and American Studies and Culture at Washington State University (WSU). Bloodsworth-Lugo is currently graduate director for the American Studies and Culture PhD programme at WSU and Elma Ryan Bornander Honors Chair Professor in the Honors College. She has published extensively in the areas of 9/11 cultural production, narratives of disease and contagion, and race and racism in U.S. popular culture.

Carmen R. Lugo-Lugo is professor of comparative ethnic studies and director of the School of Languages, Cultures, and Race at Washington State University. She has published numerous articles and book chapters on cultural constructions of race, culture, citizenship, immigration, and gender.

References

Anderson, Benedict. 2016. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. New York: Verso.

Aschwanden, Christie. 2020. ‘How ‘Superspreading’ Events Drive Most COVID-19 Spread’. Scientific American, June 23, 2020. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-superspreading-events-drive-most-covid-19-spread1/.

Associated Press. 2020. ‘150 Cannery Workers are in Forced Quarantine

Without Pay at L.A. Hotel after 3 Tested Positive for Coronavirus, Suit

Claims’. KTLA5, June 20, 2020.

https://ktla.com/news/local-news/150-cannery-workers-are-in-forced-quarantine-at-l-a-hotel-without-pay-suit-claims/.

Barreda, Virginia and Zach Urness. 2020. ‘Newport Seafood Plant has 124 COVID-19 Cases, the Second-Largest Outbreak in Oregon’. Salem Stateman’s Journal, June 8, 2020.

BMJ. 2020. ‘High Rate of Symptomless COVID-19 Infection Among Grocery Store Workers: Those in Customer-Facing Roles Five Times as Likely to Test Positive as Their Colleagues’. ScienceDaily, October 30, 2020. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2020/10/201029191116.htm.

Branswell, Helen. 2020. ‘“Essential Workers” Likely to Get Earlier

Access to Covid-19

Vaccine’. Stat, November 23, 2020. https://www.statnews.com/2020/11/23/essential-workers-likely-to-get-earlier-access-to-covid-19-vaccine/.

Bredemeier, Ken. 2020. ‘Trump: “I Beat This Crazy, Horrible China Virus.” VOA News, October 11, 2020. https://www.voanews.com/a/2020-usa-votes_trump-i-beat-crazy-horrible-china-virus/6196998.html.

Cacho, Lisa Marie. 2012. Social Death: Racialized Rightlessness and the Criminalization of the Unprotected. New York: New York University Press.

Canetti, Elias. 1984. Crowds and Power. Translated by Carol Stewart. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

CDC. 2020. ‘Health Equity Considerations and Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups’. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, April 19, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/race-ethnicity.html.

Chang, Serina, Emma Pierson, Pang Wei Koh, Jaline Gerardin, Beth Redbird, David Grusky, and Jure Leskovec. 2020. ‘Mobility Network Models of COVID-19 Explain Inequities and Inform Reopening’. Nature 589: 82–7. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-020-2923-3.

Cowan, Jill. 2020. ‘Warehouse Workers in a Bind as Virus Spikes in

Southern

California’. The New York Times, July 14, 2020.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/09/us/coronavirus-ca-warehouse-workers.html.

Das Acevedo, Deepa. 2020. ‘Essentializing Labor Before, During, and After the Coronavirus Pandemic’. U of Alabama Legal Studies Research Paper No. 3666534. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3666534.

Douglas, Leah. 2020. ‘Mapping Covid-19 Outbreaks in the Food System’. Food and Environment Reporting Network, April 22, 2020. https://thefern.org/2020/04/mapping-covid-19-in-meat-and-food-processing-plants/.

Durkee, Alison. 2020. ‘Nearly a Third of Americans Believe COVID-19

Death Toll

Conspiracy Theory’. Forbes, July 21, 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/alisondurkee/2020/07/21/nearly-a-third-of-americans-believe-covid-19-death-toll-conspiracy-theory/?sh=6011383740ab.

Espiritu, Yen Le. 2003. Home Bound: Filipino American Lives

Across Cultures,

Communities, and Countries. Berkeley, CA: University of California

Press.

Falk, Gene, Isaac A. Nicchitta, Emma C. Nyhof, and Paul D. Romero. 2021. Unemployment Rates During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Congressional Research Service, R46554 Version 20, August 20, 2021. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R46554.pdf.

Ferrier, Pat. 2020. ‘COVID-19 Cases Climb at Walmart Distribution Center; Virus Hits Construction Trades’. Coloradoan, June 3, 2020. https://www.coloradoan.com/story/news/2020/06/03/coronavirus-cases-grow-walmart-distribution-center-loveland/3137117001/.

Fisher, Ben. 2020. ‘Pacific Seafood Suspends Operations at Five Locations Due to COVID-19 Outbreak’. SeafoodSource, June 9, 2020. https://www.seafoodsource.com/news/supply-trade/pacific-seafood-suspends-operations-at-five-locations-due-to-covid-19-outbreak.

Frantz, Andrea. 2020. ‘Labeled Essential, But Only When It’s Convenient’. Des Moines Register, May 31, 2020.

Ghaffary, Shirin. 2020. ‘The May Day Strike from Amazon, Instacart, and Target Workers Didn’t Stop Business. It Was Still a Success’. Vox, May 1, 2020. https://www.vox.com/recode/2020/5/1/21244151/may-day-strike-amazon-instacart-target-success-turnout-fedex-protest-essential-workers-chris-smalls.

Ghaffary, Shirin and Jason Del Rey. 2020. ‘The Real Cost of Amazon’. Vox, June 29, 2020.

Gibson, Kate and Irina Ivanova. 2020. ‘Grocery Store Workers Fear Getting Sick as Coronavirus Cases Continue to Climb’. CBS News, November 24, 2020. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/covid-cases-grocery-store-union-workers-fear-sick/.

Graeber, David. 2013. ‘On the Phenomenon of Bullshit Jobs: A Work Rant’. Strike! Magazine, August 17, 2013. http://gesd.free.fr/graeber13.pdf.

Harris, Jon. 2020. ‘Nine Employee Coronavirus Cases Force Walmart to

Shut Down Bethlehem Warehouse, Workers Say’. The Morning Call, April 2,

2020.

https://www.mcall.com/coronavirus/mc-biz-walmart-temporarily-closing-bethlehem-fulfillment-coronavirus-20200402-32vfi4sntfgodf4h7kqkzfrmui-story.html.

Hayes, Jared. 2020. ‘Study: More than 125,000 Farmworkers Have Contracted COVID-19’. EWG (Environmental Working Group), September 22, 2020. https://www.ewg.org/news-insights/news/study-more-125000-farmworkers-have-contracted-covid-19.

Heavey, Susan. 2020. ‘U.S. Pandemic Death Toll Mounts as Danger Season Approaches’. Reuters, December 3, 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/health-coronavirus-usa/u-s-pandemic-death-toll-mounts-as-danger-season-approaches-idUKL1N2IJ0NH.

Henley, Jon and Niamh McIntyre. 2020. ‘Survey Uncovers Widespread

Belief in “Dangerous” Covid Conspiracy Theories’. The Guardian,

October 26, 2020.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/oct/26/survey-uncovers-widespread-belief-dangerous-covid-conspiracy-theories.

Holmes, Seth M. 2013. Fresh Fruit, Broken Bodies: Migrant Farmworkers in the United States. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Jaggers, Zachary. 2020. ‘When We Say, “Essential Workers”, We Really Mean Essential Work’. MarketWatch, May 11, 2020. https://www.marketwatch.com/story/when-we-say-essential-workers-we-really-mean-essential-work-2020-05-08.

Jewett, Christina, Melissa Bailey, and Danielle Renwick. 2020. ‘Exclusive: Nearly 600 US Health Workers Died of Covid-19 – and the Toll is Rising’. The Guardian, June 6, 2020.

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/jun/06/us-health-workers-dying-coronavirus-stats-data.

Jones, Charisse. 2020. ‘No Masks? No Hazard Pay? Amid COVID-19 Surge,

Grocery Store Workers Demand Protections’. USA Today, November 23,

2020.

https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/2020/11/23/covid-19-grocery-workers-demand-masks-hazard-pay-amid-virus-surge/6396541002/.

Lakoff, Andrew. 2020. ‘“The Supply Chain Must Continue”: Becoming Essential in the Pandemic Emergency’. Items: Insights from the Social Sciences (blog), November 5, 2020. https://items.ssrc.org/covid-19-and-the-social-sciences/disaster-studies/the-supply-chain-must-continue-becoming-essential-in-the-pandemic-emergency/.

Lauten-Scrivner, Abbie. 2020. ‘Foster Farms COVID-19 Deaths Among Worst Work-Related Outbreaks in California, Official Says’. Merced Sun-Star, September 16, 2020. https://www.mercedsunstar.com/news/coronavirus/article245767575.html.

Lin, Rong-Gong. 2020. ‘Foster Farms to Temporarily Close Poultry

Plant after 8 Workers Die of COVID-19’. Los Angeles Times,

August 30, 2020.

https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-08-29/foster-farms-to-temporarily-close-poultry-plant-where-eight-workers-have-died.

McCormack, Grace, Christopher Avery, Ariella Kahn-Lang Spitzer, and Amitabh Chandra. 2020. ‘Economic Vulnerability of Households with Essential Workers’. American Medical Association 324 (4): 388–90. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.11366.

McNicholas, Celine and Margaret Poydock. 2020. ‘Who are Essential Workers? A Comprehensive Look at Their Wages, Demographics, and Unionization Rates’. Working Economics Blog, Economic Policy Institute, May 19, 2020. https://www.epi.org/blog/who-are-essential-workers-a-comprehensive-look-at-their-wages-demographics-and-unionization-rates/.

Merced Sun-Star. 2020. ‘Foster Farms Allowed to Reopen Livingston Facility, Following COVID-19 Outbreak’. Merced Sun-Star, September 7, 2020. https://www.mercedsunstar.com/news/coronavirus/article245554155.html.

Molina, Brett. 2020. ‘Jeff Bezos Could Become World’s First Trillionaire, and Many People Aren’t Happy About It’. USA Today, May 14, 2020. https://www.usatoday.com/story/tech/2020/05/14/jeff-bezos-worlds-first-trillionaire-sparks-heated-debate/5189161002/.

NCFH. 2020. ‘COVID-19 in Rural America: Impact on Farms &

Agricultural Workers’.

National Center for Farmworker Health. Last modified April 22, 2021. http://www.ncfh.org/msaws-and-covid-19.html.

Newall, Mallory. 2020. ‘More Than 1 in 3 Americans Believe a ‘Deep State’ is Working to Undermine Trump’. Ipsos, December 30, 2020. https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/news-polls/npr-misinformation-123020.

Palmer, Annie. 2020. ‘Amazon Says More Than 19,000 Workers Got Covid-19’. CNBC, October 1, 2020. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/10/01/amazon-says-more-than-19000-workers-got-covid-19.html.

Perez, Sarah. 2020. ‘COVID-19 Pandemic Accelerated Shift to E-Commerce by 5 Years, News Report Says’. Tech Crunch, August 24, 2020. https://techcrunch.com/2020/08/24/covid-19-pandemic-accelerated-shift-to-e-commerce-by-5-years-new-report-says/.

Reiley, Laura, and Beth Reinhard. 2020. ‘Virus’s Unseen Hot Zone: The American Farm’. The Washington Post, September 24, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/09/24/seasonal-farm-workers-coronavirus/.

Rupar, Aaron. 2020. ‘“It Affects Virtually Nobody”: Trump Erases Coronavirus Victims as US Death Toll Hits 200,000’. Vox, September 22, 2020. https://www.vox.com/2020/9/22/21450772/trump-swanton-ohio-rally-coronavirus-affects-virtually-nobody.

Sainato, Michael. 2020. ‘“I Cry Before Work”: US Essential Workers Burned Out Amid Pandemic’. The Guardian, September 23, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/sep/23/us-essential-workers-coronavirus-burnout-stress.

Schneider, Daniel, and Kristen Harknett. 2020. ‘Essential and Unprotected: COVID-19-Related Health and Safety Procedures for Service-Sector Workers’. Shift. Research Brief, May 2020. https://shift.hks.harvard.edu/files/2020/05/Essential-and-Unprotected-COVID-19-Health-Safety.pdf.

Selasky, Susan. 2020. ‘Kroger, Other Retailers See “Eye-Popping Profits” as Workers Reap Little Benefit’. Detroit Free Press, December 4, 2020. https://www.freep.com/story/news/local/michigan/2020/12/04/kroger-walmart-amazon-profits-covid-19-pandemic/6458910002/.

Stojanovic, Dejan. 2000. The Shape. New York: New Avenue Books.

Surowiecki, James. 2005. The Wisdom of Crowds. New York: Anchor Books.

U.S. Department of Labor. 2021. ‘Essential Protections During the COVID-19 Pandemic’. DOL. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/pandemic.

Vazquez, Kevin. 2021. ‘Essential Workers Did Not Ask to be “Heroes”. On Labor, May 3, 2021. https://onlabor.org/essential-workers-did-not-ask-to-be-heroes/.

Welling, Dominic. 2020. ‘UPDATE: Another ‘Major Outbreak’ of COVID-19 at Pacific Seafood Plant’. Intra Fish, September 25, 2020. https://www.intrafish.com/processing/update-another-major-outbreak-of-covid-19-at-pacific-seafood-plant/2-1-881976.

Westwood, Sarah. 2020. ‘White House Formally Declaring Teachers Essential Workers’. CNN, August 21, 2020.

https://www.cnn.com/2020/08/20/politics/white-house-teachers-essential-workers/index.html.

White, Dawson. 2020. ‘81 Employees at Walmart Test Positive for COVID-19’. SouthCoast Today, May 3, 2020. https://www.southcoasttoday.com/news/20200503/81-employees-of-one-massachusetts-walmart-test-positive-for-coronavirus.