Care and crowdsourcing

—

On 19 February 2016, a symposium called ‘Crowdsourcing Care: Health, Debility, and Dying in a Digital Age’ was held at the University of Washington (UW), Seattle. The event was sponsored by the Simpsons Center for the Humanities, and organized by Lauren Berliner (UW Bothell, Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences) and Nora Kenworthy (UW Bothell, Nursing & Health Studies). Many of the speakers held positions in multiple departments, and many departments were represented, including anthropology; ethnic studies; science and technology studies; Slavic languages: information; gender, women, and sexuality studies; human-centered design; and communication. A few community members were also present.

Introductory remarks; Or, why did this event take place?

Noting an increasing trend in normalizing the practice of online crowdsourcing to fund medical bills, Berliner and Kenworthy created this symposium as a forum for individuals at various stages of research into this issue to share ideas in a cross-disciplinary fashion. Crowdsourcing includes utilizing online platforms to create a webpage that describes the narrative of a person or idea requiring financial help, and provides a web-based way for readers to contribute money. For example, an independent film might create a crowdsourcing page describing the film, its goals, and what the money will be used for in order to elicit donations. Increasingly, medical institutions advise patients to crowdsource funds to pay for their medical bills. The symposium aimed to explore crowdsourcing in its growing relation to the medical realm.

What is crowdsourcing?

The most striking aspect of the symposium was the multiple definitions and meanings of ‘crowdsourcing’ used by participants. While some used the term to refer to online platforms to garner monetary funds, other participants gave historical examples of communities that raised resources for an individual community member through other means. Dr. Janelle Taylor (Anthropology, UW Seattle) noted in her closing remarks that symposium speakers used the terms ‘crowdsourcing’ and ‘care’ in multiple ways. Care was defined as a practice, moral experience, moral economy, and discourse of power. Crowdsourcing was noted as not being limited to specific technologies (such as online platforms).

Taylor posed the questions: Where do we want to draw the definitional boundaries of ‘crowdsourcing’? Why? For what use? She discussed the value of keeping in mind the differences and utility of each specific use of a term when conducting research„ posing the question: ‘Forget what it is; what does it do?’

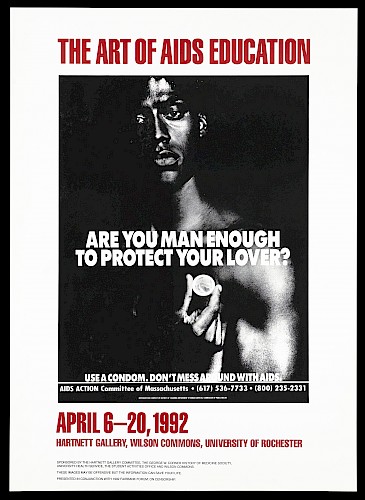

Artifacts

Gina Neff provided a FitBit self-tracking device as an artifact for discussion during the symposium's workshop component.

The symposium invited speakers to bring in physical artifacts that represented their experiences of crowdsourcing as related to their research projects. The artifacts gave materiality to crowdsourcing, oft thought of as ephemeral and limited to the online world. Fifteen participants presented artifacts with which to think through crowdsourcing and care. Artifacts included screenshots of a newspaper article from 1936, printouts of various web pages, copies of photographs shot during fieldwork, and a brochure on how to crowdfund to pay for medical care.

Speaker: Kalindi Vora

Kalindi Vora (Ethnic Studies; University of California, San Diego) linked her past and current research projects together by discussing analytics that take into account the agency exhibited by oppressed groups and the necessary (unpaid) labor the groups provide. Vora’s previous research at an Indian assisted reproductive technology clinic discussed multiple forms of care and provided weight to the argument that care is a luxury. Various economies (such as gift and donation) were shown at play. Vora drew upon Gayatri Spivak’s idea of ‘affectively necessary resources’ to think through the unpaid emotional labor required to successfully embody the role of a surrogate. Vora’s new project on online forum users with chronic pain was presented as a rerouting of knowledge and power. CrowdMed (https://www.crowdmed.com), a website where a group decides on a diagnosis for an individual, was offered as an example of alternative identities and economies; the underlying need for a group to diagnose an individual cropped up as a consequence of capitalism.

Roundtable

Four speakers discussed their work in relation to crowdsourcing. In the question-and-answer period after the brief presentations, a participant voiced the idea that crowdsourcing perpetuates and allows space for broken capitalist health care systems. The format of a roundtable correlates well to crowdsourcing, but while there was some conversation among discussants, the use of a roundtable as a modality and metaphor for crowdsourcing was underused. Timing constraints may have limited greater group discussion concerning each presenter’s work.

Christoph Hanssmann (Sociology, UC San Francisco) spoke on transgender health, the stratification of care, and the politics of diagnosis through the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases online revision process. Hanssmann also touched on various online crowdsourcing platforms, including those for Miss Major Griffin-Gracy, a trans woman community leader and activist. Also mentioned was Lohana Berkins, a travesti activist from Argentina. Hanssmann showed that online crowdsourcing exists in different forms for different purposes than solely asking for monetary donations to help out in an isolated event.

Gina Neff (Communications, UW Seattle) spoke on self-tracking. Many individuals already self-track without any devices, for example, when a parent cares about a child’s health by noting the child’s dietary patterns. The question of who controls a person’s data was posed. Neff presented the example of The Nightscout Foundation, a group of parents who developed open-source technology to look after their children’s diabetes.

José Alaniz (Disability Studies and Slavic Languages and Literature, UW Seattle), a scholar of comics, spoke on the representation of grief and death, and the potential of graphic art for social justice, collaborative methods, and a different grammar with which to communicate ideas. Alaniz discussed the works of two graphic artists exhibited in the Feminist Pencil Exhibit: Tatyana Kushkhutdinova and Yanka Smetanina.

Sasha Su-Ling Welland (Anthropology, and Gender, Women and Sexuality Studies, UW Seattle) spoke about her preliminary research on ‘cancer aesthetics’. One of the questions that emerged concerned how anger is pacified or shut out of the experience of cancer. Welland touched on the feminist critiques of allowable narratives, specifically of Hannah Wilke and Audre Lorde. Welland mentioned bringing individual narratives together in research through the method of social biography.

Speaker: Brian Goldfarb

Brian Goldfarb (Communication, UC San Diego) presented his collaborative research with Somali immigrants in San Diego that seeks to understand mental health issues as understood by the community. One of the research goals is to create an app for mHealth ‘to support community negotiation of mental health literacies’. Community-defined mental health issues (such as excessive social media usage) were formatted for tablets through comic narratives that would be used ‘around the dinner table’ in a group fashion. Goldfarb discussed his research project as dialogic, moving beyond cultural competence to research that includes mutual vulnerability and interdependency between researchers and community members. Goldfarb also provided a rich history of crowdsourcing through examples of early Internet use. Other individuals, including Kathleen Woodward (English, Director of the Simpson Center for the Humanities, UW Seattle), discussed how crowdsourcing existed before the Internet.

A few concluding remarks

In addition to pointing out how both crowdsourcing and care were used in multiple ways throughout the symposium, and asking participants to consider the specificity and utility of each term, Taylor noted that one connective strand throughout the symposium was the force and power of narratives in the world. Concepts offered for pondering narrativity’s importance included affect and the politics of the body.

Taylor noted that crowdsourcing was discussed as a process of mediating different systems of value. Mediation was defined as the translation of different systems. Vora’s research at the surrogacy clinic is an example of when mutual misunderstanding creates a necessary disjuncture.

Finally, Taylor problematized the contrasting of ‘care’ with ‘cure’. Cure relies on the care that it denies and hides.A cure never exists in isolation from care.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Wendy Kuijn, Erin Martineau, and Jenna Grant for their helpful guidance.

About the author

Melissa J. Liu is a PhD medical anthropology student at the University of Washington, Seattle, with a focus on dementia. She holds a master’s degree in anthropology with a concentration in medicine, science, and technology studies. She is a Neuroethics Fellow with the Center for Sensorimotor Neural Engineering.