Fake-talk as Concept and Method

What’s at Stake in the Fake? Indian Pharmaceuticals, African Markets and Global Health

—

Published: 27 September 2023

Fake

Pharmaceuticals

Health

Evidence

Suspicion

https://doi.org/10.17157/mat.10.3.7291

Abstract

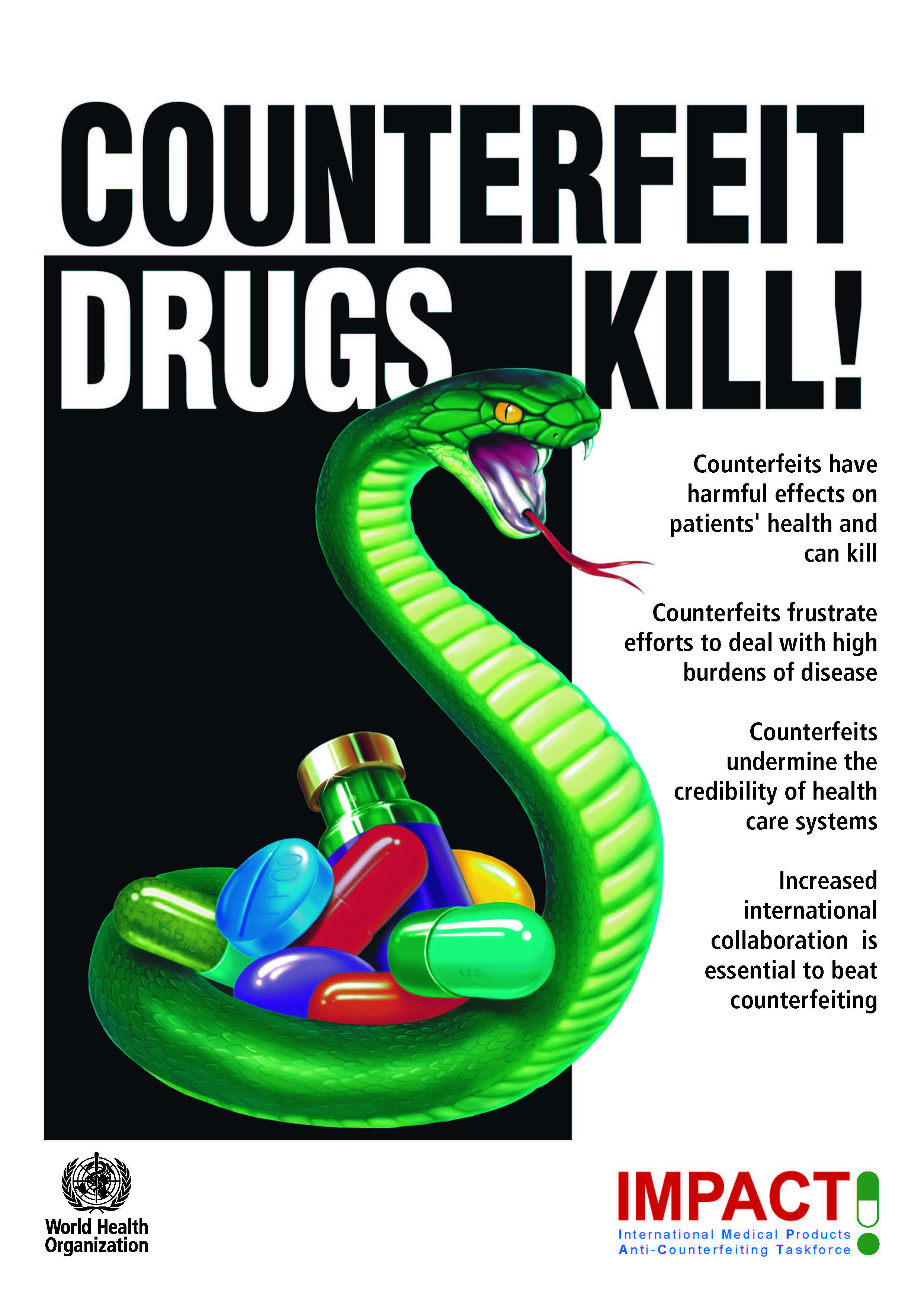

In a world seemingly awash with fakes—or at least accusations of fake-ness—it is not only difficult to discern what is ‘real’ but also to know what to make of such a proliferation of worries about fakes. In this article, a manifesto of sorts for the Special Section, we outline how the problem of ‘fake drugs’ in particular allows us to understand the phenomenon of fakes in general. We introduce the conceptual and methodological tool of ‘fake-talk’ as it allows us to make sense of claims about fake drugs and of the power these claims hold. We develop our argument through a close reading of specific ethnographic examples drawn from the work of our colleagues in the project ‘What’s at Stake in the Fake? Indian Pharmaceuticals, African Markets and Global Health’. We show that fake-talk thrives on a lack of evidence, imports urgency, and is expressive. Taking fakes seriously as a force in themselves enables us to see how fakes are freighted with—and deploy—everyday articulations of otherwise unfathomable discomforts, predicaments, and anxieties of our time.